Is Indivior a Good Steward of Its Opioid Treatments?

Fierce Pharma reported in 2020 that the former Indivior CEO was sentenced to six months in federal prison for his role in misleading officials about the supposed dangers of Suboxone tablets. He was also fined $100,000 and forfeited another $500,000. But it seems now he’d like to be a consultant to individuals or companies attempting to bring a new drug to market. However, the FDA rejected that plan for now. On February 27, 2023 he was debarred by the FDA for “5 years from providing services in any capacity to a person that has an approved or pending drug product application.” What was he involved in that resulted in his prison sentence and debarment by the FDA?

According to Fierce Pharma, on October 23rd, 2023, Indivior agreed to pay $385 million to settle lawsuits in the U.S. brought by drug wholesalers claiming it illegally suppressed generic competition for Suboxone. But that’s not all. The company also agreed in June of 2023 to pay $102.5 million to settle a 2016 lawsuit charging that Indivior’s actions when switching from a tablet to an oral film form version of Suboxone was done to extend its monopoly with Suboxone. AND in August of 2023, it offered $30 million to settle with health plans making similar claims. This was in addition to the $300 million Indivior paid in 2021 to resolve claims it “falsely and aggressively” marketed the drug, which led to the misuse of state Medicaid funds.

All this happened after Indivior was sued in 2020 by its former parent company, Reckitt Benckiser, seeking $1.34 billion in damages tied to its marketing scheme for Suboxone film. Then on December 20, 2023 Indivior announced that it had entered into a settlement agreement with Actavis Laboratories, a subsidiary of Teva Pharmaceuticals, to resolve patent disputes regarding Actavis’s Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) for generic buprenorphine and naloxone sublingual film. Under the settlement, Actavis can launch the generic film products in ANDA no earlier than January 31, 2025.

It seems Indivior as a company is trying to leave its chaotic and costly past behind. In About Us, Indivior said it “is a global pharmaceutical company working to help change patients’ lives by pioneering life-transforming treatment for addiction and other serious mental illnesses.” Their vision is to provide access to evidence-based treatment to the millions of people across the globe who suffer from substance use and serious mental illness. They also say they take their role as a steward of their medications extremely seriously:

We cultivate a culture of integrity and commit ourselves to the highest standards of governance. We believe our long-term success is directly linked to operating in a responsible way and in a way that minimizes our impact on the environment. We support efforts to educate around safety and proper use of our medication-assisted treatments.

Origins of Indivior

In case you’re not familiar with the company, here is a brief history of Indivior from Wikipedia and “The Opioid Buzzard.” It was established as the buprenorphine division of Reckitt Benckiser in 1994. Suboxone and Subutex were approved for the treatment of opioid addiction in October of 2002. They were both sublingual (under the tongue) tablets. Suboxone consists of buprenorphine and naloxone; Subutex was just buprenorphine. They came to market in 2003.

In 2007 Reckitt Benkiser (RB) acquired the rights for the sublingual film version of Suboxone from MonoSol Rx. RB knew its patent exclusivity for Suboxone and Subutex would expire in 2009, so they submitted a New Drug Application for the film version of Suboxone, which was approved in August of 2010. In their 2011 annual report (no longer retrievable from its website), RB indicated to their shareholders that competition from generics could take up to 80% of the revenue and profit from the U.S. Suboxone market. But they expected “that the Suboxone film will help to mitigate the impact.”

In September of 2012 RB announced that they were voluntarily withdrawing Suboxone tablets from the market because of data they had received from the U.S. Poison Control Centers suggesting there were higher rates of pediatric overdose on the tablet formulation than the film version. They said they would take the tablet form off the market to “protect public health and safety.” The very same day RB filed a “Citizen’s Petition” with the FDA calling for the agency to postpone the approval of generic version of Suboxone in the interests of public safety. Subutex tablets were discontinued in 2011 and Suboxone tablets met the same fate in in 2012. For more on this action by RB, see “The Opioid Buzzard.”

In December 2014 Reckitt Benckiser made the buprenorphine division a separate company named Indivior. By February 2015, it was capitalized on the London Stock Exchange at $3.1 billion. And on April 9th 2019, a federal grand jury indicted Indivior for allegedly engaging in an illicit national scheme to promote Suboxone. See “The Pied Pipers of Suboxone” for more on this topic.

Indivior Products for Opioid Use Disorder

The Indivior products currently available in the U.S. to treat opioid use disorder include: Suboxone, a buprenorphine and naloxone sublingual film, Opvee, a nalmefene nasal spray for the emergency treatment of known or suspected overdose of opioids, and Sublocade, an extended-release injection of buprenorphine. Opvee and Sublocade are newer products than Soboxone and will be described below.

NPR noted Opvee was developed by Opiant Pharmaceuticals, which was acquired by Indivior in March of 2023. Opvee was approved by the FDA in May of 2023 and is similar to Narcan which contains naloxone. It apparently has a longer-acting effect than naloxone, which has some experts concerned. Nevertheless, Nora Volkow, the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, said: “The whole aim of this was to have a medication that would last longer but also reach into the brain very rapidly.”

An adverse side effect of opioid reversal drugs like Narcan and Opvee is they create intense withdrawal symptoms including: nausea, diarrhea, muscle cramps, anxiety, restlessness or irritability, increased blood pressure, rapid heart rate, body aches, and others. Important Safety Information for Opvee cautioned that the use of Opvee (leading to abrupt postoperative reversal of opioid depression) “may result in adverse cardiovascular effects” in people with preexisting CV disorders. So, these patients should be closely monitored in a healthcare setting. And it warns that some patients may become aggressive when an opioid overdose is reversed (treated) with Opvee.

With naloxone (Narcan), these symptoms could last 30 or 40 minutes. With Opvee (nalmefene) they can last six hours or more, “requiring extra treatment and management by health professionals.” GoodRx Health said: Opvee’s half-life is about 11 hours, while Narcan’s half-life is about 2 hours. Read between the lines here. A person uses opioids to experience the high or euphoria AND to avoid withdrawal. So Opvee immediately blocks the high and brings on withdrawal. It extends the withdrawal symptoms to six hours or more, with the potential of the treated person wanting nothing less than to find more opioids to cope with the withdrawal and driving them to use a higher dose of opioids to overcome the nalmefene—with the potential of adverse cardiovascular effects in people with preexisting CV disorders.

If this “treatment” occurs, as is likely, outside of a healthcare facility, the person or persons who administered the Opvee will have to convince person to go to an emergency department or other healthcare facility. There is a better chance of success if the withdrawal symptoms only last 30 or 40 minutes than six hours or more. No wonder some individuals get aggressive when treated with Opvee. Should it be limited to use with overdose victims who are already in a healthcare facility or by emergency responders like EMT or police?

Dr. Lewis Nelson of Rutgers University, a former advisor to the FDA, said the risk of long-lasting withdrawal is something they try to avoid. He added a second or third dose of naloxone is easy enough to give and works perfectly well.

Indivior said it is still considering what to charge for its drug. It will compete in the same market as naloxone, where most buyers are local governments and community groups that distribute to first responders and those at risk of overdose. Indivior has told investors that Opvee could eventually generate annual sales between $150 million to $250 million.

Sublocade was approved by the FDA in November of 2017. It is a monthly injection of buprenorphine to treat individuals with moderate to severe opioid use disorder. “It is indicated for patients that have been on a stable dose of buprenorphine treatment for a minimum of seven days.” It is a drug-device combination product that is injected under the skin (subcutaneously) as a solution, but forms a solid deposit or depot of buprenorphine. After the initial formation of the depot, buprenorphine is released as the depot biodegrades.

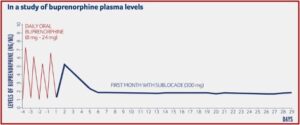

The monthly injection of buprenorphine in Sublocade is another treatment option for opioid use disorder (OUD). It has the advantage of gradually releasing buprenorphine at a controlled rate, meaning that the levels of buprenorphine stay consistent in the blood throughout the month. In a study reported on in the above-linked description on how Sublocade works, Indivior provided a chart illustrating how buprenorphine levels were delivered at sustained levels, after a required preliminary period of daily oral buprenorphine for at least 7 days to control withdrawal symptoms. The required daily use of oral buprenorphine helps assure the healthcare provider the person did in fact stop their use of opioids before they began their daily use of Suboxone because buprenorphine acts as a partial antagonist, blocking the ability of many opioids to cause an effect.

Should the person decide to stop taking Sublocade, the terminal half-life of Sublocade is 43 to 60 days. According to Drugs.com, it usually takes four to five half-lives for a drug to be totally eliminated from the body. So, no trace of buprenorphine from Sublocade should be found after 172 to 300 days. This raises the potential use of Sublocade as a tool for slow tapering once the individual has reached a steady-state (4-6 months), instead of treatment with Sublocade continuing indefinitely.

A Slow Buprenorphine Taper with Sublocade?

Dr. Leeds, a Suboxone doctor in Fort Lauderdale FL, described just such a way Sublocade could be used to taper off Suboxone. He said many patients often want to know from their first visit to a Suboxone doctor if there is a way to eventually get off Suboxone. Their reason is the buprenorphine in Suboxone is an opioid drug and causes physical dependence like all opioids. If a patient taking Suboxone quits treatment early, they will develop withdrawal symptoms. A gradual taper is the solution to minimize the physical opioid withdrawal symptoms.

However, the medication is not well-designed for a taper. Doctors who help their patients with tapering off Suboxone quickly realize that the Suboxone sublingual films are not available in enough dosage increments to all for proper gradual tapering.

In order to avoid serious withdrawal symptoms, a patient most often must reduce their dosage gradually, to the lowest dose possible, such as buprenorphine 0.25mg daily, or even less. Unfortunately, the lowest Suboxone dose is 2mg.

Additionally, the manufacturer, in the Suboxone prescribing information, states that patients should not cut or split the tablets or films. Suboxone makers are clearly not interested in helping patients with tapering off Suboxone.

Dr. Leeds noted that since the subcutaneous buprenorphine shot takes many months to fully wear off, “it does seem possible that it might help some patients with the tapering process.” However, the buprenorphine taper would be off-label and experimental at this point. There would be no available guidance from experts, “because Sublocade has not been widely used for Suboxone tapering.”

For the present, he does not recommend finding a doctor willing to use Sublocade to taper off Suboxone. But he encouraged interested people to reach out to researchers and research centers in the field of opioid use disorder treatment. “If Suboxone scientists are aware that people are interested in this research, they might decide to seek funding for such studies.” He also suggested there may be doctors who are using Sublocade off-label for Suboxone tapering, who may have anecdotal information to help other interested doctors.

Drugmakers are quick to recommend that doctors get their patients onto their medications. Yet, they do little to guide doctors in getting patients off of these meds when treatment has been completed.

Are you listening, Indivior? You describe yourself as “a global pharmaceutical company working to change patients’ lives by pioneering life-transforming treatment for addiction.” You further said you believed your “long-term success was directly linked to operating in a responsible way.” Is it responsible to neglect to provide guidance for individuals who would like to taper off their use of Suboxone and Sublocade, which are opioids—meaning they make their users physically dependent on them. Does the safe and proper use of your medication-assisted treatments require you to ignore those who want a safe and proper method of tapering off of them?

If you truly take the stewardship of your medications extremely seriously, shouldn’t you be willing to fund research into Suboxone tapering with Sublocade?