Never Enough and Adaptation

In “Never Enough and No Free Lunch,” we looked at what Judith Grisel identified as the three laws of psychopharmacology from her book, Never Enough. She recalled a time when giving a brief lecture to a group of high school students on the opponent-process theory of Solomon and Corbit. A student leaped to his feet and cried out, “This changes my life!” She said she shared his sentiments and added that the theory was important because it largely “set the course” for how scientists think about and study addiction.

Richard Solomon and John Corbit proposed that every stimulus that disturbs the way we feel is counteracted by the nervous system in order to bring the body back to an emotional “set point” or homeostasis. In their description of the theory in a 1974 article for Psychological Review, “An Opponent-Process Theory of Motivation,” they said addiction did not differ in principle from any acquired motivational system. “We can easily describe opiate, alcohol, barbiturate, amphetamine, or cigarette addiction within the empirical framework of the analysis we have proposed.”

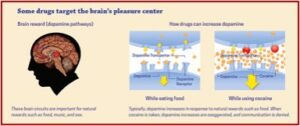

Grisel said Solomon and Corbit suggested that feeling states are maintained around a “set point” like body temperature is. Any feeling, such as being happy, depressed or excited, represents a disruption of the stable feeling state or homeostasis. The opponent-process theory suggests that “any stimulus that alters brain functioning to affect the way we feel will elicit a response by the brain that is exactly opposite to the effect of the stimulus.” The fact that our feeling states are so tightly constrained has important implications for understanding drug abuse. The brain learns by adapting to every drug that affects its function.

Some of these changes are relatively transient, like tachyphylaxis [an acute, sudden decrease of response to a drug after its administration, rendering it less effective] in an occasional drinker, but as learning is stronger with repetition, chronic exposure to a drug results in more lasting alterations. For some drugs, such as antidepressants, adaptation is actually the therapeutic point. Developing tolerance to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may help to change a pathological affective “set point” so that being depressed is no longer the patient’s normal state. . . .As the brain adapts to a drug of abuse and the drug becomes less effective at stimulating dopamine transmission, a user must take more and more to produce the same high. Engaged in a futile attempt replicate the initial experiences, an addict repeatedly administering the drug ensures more and more adaptation.

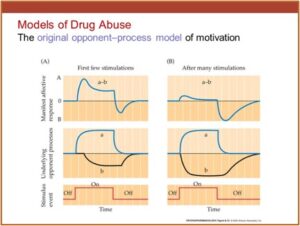

In the following charts, the A process is what the drug does to the brain and the B process is the brain’s response or adaptation to the drug, as it attempts to return the brain to its neutral, homeostatic state. State A can be pleasant or unpleasant, but whatever it is, State B is the opposite. The set point is the line in the middle. Large doses of a drug produce large A processes, and long-lasting stimulations produce long-lasting A processes.

When the brain is first exposed to a drug, the high or A process is not initially dampened by the B process of the brain trying to return to a neutral, homeostatic state. This leads to an initial peak experience followed by a leveling off. The A process in the brain is always the same if the same amount of the drug is used, but this is not true for the B process. Generated by an adaptive nervous system, the b process learns with time and exposure. “Repeated encounters with the stimulus (or use of the drug) result in bigger, faster, and longer-lasting B processes that are better able to maintain the homeostasis in the face of further stimulation.” Another thing to know is the B process can be triggered by environmental cues that signal an A process is coming. In other words, it can trigger the A process.

After many times of getting high, an adaptation results and there is hardly a bump in the feeling (euphoric) state. The drug then functions primarily as a way to hold off withdrawal and craving in the b process, in the face of the brain’s ability to counteract the A process until drug use is stopped, then withdrawal and craving begins in earnest. The classic illustration of this is with opioids like heroin.

This model also explains why the states of withdrawal and craving from a drug are always exactly opposite to the drug’s effects. If a drug makes you feel relaxed like benzodiazepines, withdrawal and craving are experienced as anxiety and tension. If a drug helps you wake up like caffeine, adaptation includes a lack of energy and enthusiasm. If it reduces the sensation of pain like opioids do, feeling pains you didn’t know you had will happen.

The common symptoms of addiction are tolerance, withdrawal and craving, and they are embedded in the consequences of the B process. Tolerance occurs because more drug is needed to produce an A process capable of overcoming an increasingly stronger b process. Withdrawal happens because the B process outlasts the drug’s effects (see the charts above). Craving is almost guaranteed by the opponent-process model, because any environmental cue that became associated with the drug (through classical conditioning) can trigger a B process because the learning cycle or ritual that included the cue or trigger was repeated many times as the person used drugs.

This happens because of what Jeffrey Schwartz called the Quantum Zeno Effect, in You Are Not Your Brain. This means the brain areas activated by a drug are stabilized and held in place long enough so they can be wired together by Hebb’s Law. Hebb’s Law says neurons that fire together wire together. Once any sequence of neurons is wired together, the brain will respond to similar situations in a reliably “hard wired” way. So, any environmental cue that occurred repeatedly within the sequence of neurons or the ritual of “getting high” has the potential to become a trigger and initiate craving. In Never Enough, Judith Grisel gave a personal example of the incredible power of this cognitive memory process.

I was clean for close to two years and had been volunteering in my biopsychology professor’s laboratory to get some research experience. One part of the protocol required daily administration of an experimental drug into the subjects’ (rats) peritoneum, which is the sac that loosely constrains the abdominal organs. The standard procedure is to cup the rat gently in one hand, insert the needle with the other, and create negative pressure by pulling slightly back on the needle to be sure the injection isn’t going straight into a blood vessel. I thought I’d fully extinguished any personal associations by this time, but one day when I pulled back and the needle filled with blood, I heard clamorous ringing in my ears and a taste in my mouth that were characteristic of cocaine going into my vein. It was years later, in a completely different context, and I had not a whit of desire to use at that moment, but just seeing blood filling the syringe cause an instantaneous reaction. I let my colleague finish the injections and went back to my dorm sobered by the astounding power of memory.

The brain is so well organized to counteract things that cause it anxiety or unease, that it uses its learning skills to anticipate the disturbance a drug will cause rather than wait for the drug effects themselves. It starts a B process, from which you experience craving. In other words, the brain begins to dampen the drug effects before you even take the drug! So, there is a real potential for cue-induced relapse to occur and addicts need to become aware of this danger and develop a plan ahead of time, before the B process activates, to manage it if it occurs.

Originally posted on July 6, 2021