Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Christian Nationalism

After reading Paul Miller’s book, The Religion of American Greatness, I became aware of the problems of thinking of America as a “Christian Nation.” Simply put, it is a political ideology with a Christian gloss. I was relatively unaware of Christian nationalism until then, but was persuaded by his arguments. He wrote an article for Christianity Today, “What Is Christian Nationalism” where he noted that many of the rioters on January 6th, 2021 had Christian signs, slogans or symbols. “But none of this should be confused with the Christian’s identity in the transnational family of God, and no national political agenda or ideal can take priority over God’s global mandate and mission for his people.” It takes the name of Christ as a fig leaf to cover its political program, “treating the message of Jesus as a tool of political propaganda and the church as the handmaiden and cheerleader of the state.”

As Miller noted in his article, the term “Christian Nationalism” is a relatively new term, one which it seems many Americans are not familiar with. Slate said the term was “in the air” after January 6th rioters came to the Capitol waving Christian symbols and banners. But it has been embraced by others, including Marjorie Taylor Greene. She even hocked a Proud Christian Nationalist tee shirt in her Official MTG Shop. She also posted on X, formerly known as Twitter, that she was honored to meet Jake Chansley, the infamous QAnon shaman from January 6th.

The Pew Research Center also noted growing numbers of Americans were embracing the Christian Nationalist label, while others still saw it as a danger. Pew said their survey found most American adults believed the founding fathers intended the country to be a Christian nation (60%), with many affirming (45%) it should be a Christian nation today. When the survey’s respondents were separated into those who think the U.S. should be a Christian nation and those who did not, some interesting difference emerged. Among those who thought the U.S. should be a Christian nation, only 28% thought the country should openly declare it. Fifty-two percent thought no religion should be the official religion of the country.

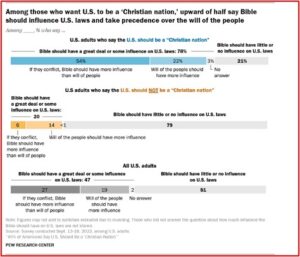

Among those who thought the U.S. should not be a Christian nation, 1% thought the U.S should openly declare it, and 88% rejected the idea. Similar differences were found with whether the state should advocate for Christian religious values, or moral value shared by people of many faiths. And whether or not to enforce or stop enforcing the separation of church and state. See the Pew link for a graphic. Those who want the U.S. to be a Christian nation tended to want the Bible to have a great deal or some influence on U.S. laws (78%), while those opposed to the idea soundly rejected the idea (79%). See the chart below, found in the Pew article.

The Pew survey results disturbingly resonate with what Paul Schreiner called the “bad form” of Christian nationalism. This is a fusion of Christianity and civil life, where instead of persuasion, adherents seek to enact and enforce laws. This is attempting to bring about the kingdom of God by power and command, not by the Spirit of God. Schreiner acknowledged the distinctly Christian history of America, but noted how this sense of Christian nationalism goes against key features of the American experiment, namely pluralism and religious liberty.

Eliminating all dissent might sound attractive, and it certainly would allow governing authorities to get things done more quickly. But squashing dissent violates human liberty, equality, and the vision of the founding fathers. It requires coercion of and change from those who dissent. If taken to its logical conclusion, this Nationalism undermines the foundation of a free society. Should such a fusion dominate American civil life, it would divide the nation rather than unify it. Uniformity in some aspects of national life isn’t all bad, but that must always exist beside diversity.

See “What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism?” or Paul Schreiner’s article, “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Christian Nationalism” for a more through critique and discussion of this point.

Perhaps many of the Pew survey participants didn’t have a well-thought-out understanding of the nuances within so-called “Christian nationalism.” This seems to have been the case. Half of the Pew survey respondents were asked if they have heard the term “Christian nationalism.” Overall, 54% of Americans said they had never heard it. Non-Christians tended to be more familiar with the term (55%). But atheists (78%) and agnostics (63%) were most familiar. See the table below, found in the Pew article.

Schreiner warned that the “bad” form of Christian Nationalism becomes “ugly” when it “idealizes and advocates for a fusion of Christianity with American life and does so by dominion. This is the type of Christian Nationalism exhibited by some on January 6.” This conflates God and country, confusing the categories of Christian faith and nation-state and advocates for its goals by force or violence when deemed necessary. “No nation-state can be a Christian nation-state, because Christianity doesn’t work that way.” Here, the fig leaf referred to in the opening paragraph comes off and Christian nationalism is exposed as a political program of nationalism.

Jake Chansley, the infamous QAnon shaman from January 6th was sentenced and imprisoned for 27 months. At his parole hearing, he expressed remorse for his actions and said he no longer wanted to be known as the QAon Shaman, saying he was wrong to enter the Capitol . He was released into a Phoenix halfway house for ex-offenders. Seemingly unrepentant for his actions, he is now running for Congress in the state of Arizona as a Libertarian and has again embraced his role as the QAnon Shaman. Look at the link to “X” above where Marjorie Taylor Greene said she was honored to meet him. Also see his own Twitter feed.

In “What Is Christian Nationalism?” Paul Miller distinguished between Christian nationalism and nationalism. Miller said nationalism is the belief that humanity is divisible into mutually distinct culture group defined by shared language, religion, ethnicity, or culture. They should have their own governments; the governments should promote and protect a nation’s cultural identity. Sovereign national groups then provide meaning and purpose for human beings.

The problem is, humanity is not easily divisible into mutually distinct cultural groups. “Cultures overlap and their borders are fuzzy.” They make a poor fit as the foundation for political order. Whereas cultural identities are fluid and hard to draw boundaries around, political boundaries are hard and semipermanent. “Cultural pluralism is essentially inevitable in every nation.” Attempts to found political legitimacy on cultural likeness means the political order will consistently be felt to be illegitimate by some group.

In the absence of moral authority, nationalists can only hope to establish themselves by force. “Scholars are almost unanimous that nationalist governments tend to become authoritarian and oppressive in practice.” Miller observed that when Protestantism was a “quasi-official religion” in the U.S., “it did not respect true religious freedom.” Christianity was also used by the U.S. and many individual states to support slavery and segregation.

Miller thought Christian nationalism was the belief that the American nation is defined by Christianity; and the government should take steps to keep it that way and continue to be so in the future—to promote a specific cultural template as the “official” culture of the country. There may be some who want an amendment to the Constitution to recognize America’s Christian heritage. They strive to enshrine a Christian nationalist interpretation of American history in school curricula; that America has a special relationship with God; that it was chosen by him to carry out a special mission on earth. Others advocate for immigration restrictions to prevent changes to American ethnic demographics or a change to American culture. Others want to empower the government to take stronger action against immoral behavior.

Christian nationalism tends to treat other Americans as second-class citizens. If it were fully implemented, it would not respect the full religious liberty of all Americans. Empowering the state through “morals legislation” to regulate conduct always carries the risk of overreaching, setting a bad precedent, and creating governing powers that could be used later be used against Christians. Additionally, Christian nationalism is an ideology held overwhelmingly by white Americans, and it thus tends to exacerbate racial and ethnic cleavages. In recent years, the movement has grown increasingly characterized by fear and by a belief that Christians are victims of persecution. Some are beginning to argue that American Christians need to prepare to fight, physically, to preserve America’s identity, an argument that played into the January 6 riot.

Christianity is a religion focused on the person and work of Jesus Christ as defined by the Christian Bible and the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds. It is the gathering of people “from every nation and tribe and people and language,” who worship Jesus (Revelation 7:9), a faith that unites Jews and Greeks, Americans and non-Americans together. Christianity is political, in the sense that its adherents have always understood their faith to challenge, affect, and transcend their worldly loyalties—but there is no single view on what political implications flow from Christian faith other than that we should “fear God, honor the king” (1 Peter 2:17), pay our taxes, love our neighbors, and seek justice.

Miller said normal Christian political engagement is humble, loving and sacrificial. It rejects the idea that Christians are entitled to primacy of place in the public square or that Christians have a presumptive right to continue their historical predominance in American culture. Christians should seek to love their neighbors by pursuing justice in the public square, which includes working against abortion, promoting religious liberty, furthering racial justice, protecting the rule of law, and honoring constitutional processes. “That agenda is different from promoting Christian culture, Western heritage, or Anglo-Protestant values.”

There is a “good” sense of Christian Nationalism, meaning simply that “Christianity has influenced and should continue to influence the nation.” The Declaration of Independence affirmed that all men (and women) are created equal. They are endowed “by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Schreiner noted that such a principle was worthy of Christian advocacy alongside biblical views of marriage, sexuality, and abortion. “Our nation would be improved by affirming the goodness of natural law principles.”

In the best sense, this form of Christian Nationalism doesn’t attempt to dominate the political process or to make the nation completely Christian but seeks instead to bring change by persuasion. Rather than trying to overthrow the government, adherents advocate their cause by supporting laws, electing candidates, podcasting, writing, and developing think tanks. They won’t force their opinions, but they also won’t back down from arguing for them.

For further reflections on nationalism, see the link “Christian Nationalism” on this website.