Trends in Substance Use and Abuse

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) provides information on tobacco, alcohol, and drug use, mental health and other health-related concerns in the US. NSDUH began in 1971 and is conducted yearly in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for 2020, published in October of 2021, interviewed almost 70,000 people. It is directed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), an agency in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NSDUH has been conducted by RTI International, a nonprofit research organization in North Carolina.

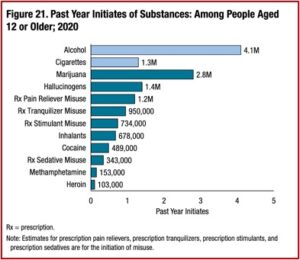

Criteria from the DSM-5 were used in order to categorize the substance use disorders (SUD) of the respondents. SUDs are classified by impairment caused by the recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs, including health problems, disability, and the failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Respondents were said to have an SUD if they had two or more of the eleven criteria noted on page 27 of the 2020 NSDUH survey. The following figure provided an overview of the number of people aged 12 and older who initially used the noted substances in the past 12 months.

A surprising finding was that there are more people trying hallucinogens for the first time in the past year than cigarettes. This is likely a result of popular and research interest into using hallucinogens such as ketamine and MDMA, to treat mental health issues. See “Psychedelics Are Not a Magic Bullet”, “Give MDMA a Chance?”, “In Search of a Disorder for Ketamine” and other articles on this website.

But it should come as no surprise that the top two substances used for the first time in the past year were alcohol and marijuana. Alcohol is legal in all states and although marijuana is illegal under federal law, recreational marijuana is legal in 18 states and 37 states have legalized medical marijuana. Only in four states, South Carolina, Kansas, Idaho and Wyoming is marijuana still fully illegal. See “Map of Marijuana Legality by State.”

The above figure shows that in the past 12 months, 4.1 million people began using alcohol and 1.3 million people tried a cigarette for the first time. There also were 2.8 million new marijuana users, 1.4 million new hallucinogen users, 1.2 million people who first misused prescription pain relievers, 950,000 new misusers of prescription tranquilizers, and 734,000 new misusers of prescription stimulants. There were also 489,000 new cocaine users and 153,000 new methamphetamine users.

Despite the opioid epidemic, estimates of initial heroin use in the past year were the lowest category of new users at 103,000. Nearly 90 percent of individuals using heroin for the first time did so after the age of 25. Among adults aged 26 or older, 91,000 people initiated heroin use in 2020.

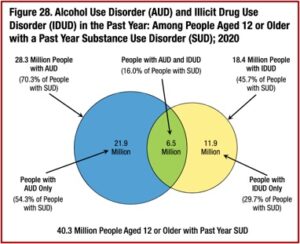

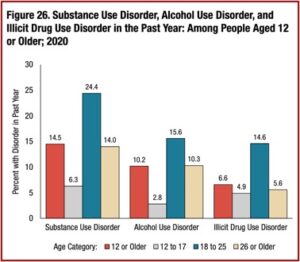

Substance use disorders are with alcohol or drugs; or a mixture of both. There were 40.3 million people 12 or older estimated as meeting the criteria for a SUD in the past year. This included 28.3 million who had an alcohol use disorder (AUD) and 18.4 million who had an illicit drug use disorder (IDUD). Among those individuals with an AUD, 21.9 million had AUD but not an illicit drug use disorder. Among the 18.4 million people with a past year IDUD, 11.9 million has an IDUD but not AUD. This meant there were 6.5 million who met the criteria for both AUD and IDUD. See the figure below.

Age is again seen as a factor with the presence of SUDs in the past year. When the figures for substance use disorder were looked at by age, the percentage of people with a past year SUD was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (24.4% or 8.2 million people). This was followed by adults 26 or older (14.0% or 30.5 million people).

Among people aged 12 or older, 10.2% (28.3 million people) has a past year AUD. The percentage of people who had past year AUD was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (15.6% or 5.2 million people). Again, this was followed by adults 26 or older (10.3% or 22.4 million people).

Among people aged 12 or older, 6.6% (18.4 million people) had an IDUD in the past year. The percentage of young adults aged 18 to 25 (14.6% or 4.9 million people) was higher than the percentages of adults aged 26 or older (5.6% or 12.3 million people) and adolescents aged 12 to 17 (4.9% or 1.2 million people). See the following figure.

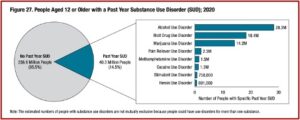

However, the vast majority of the population did not have a SUD of any kind in the past year. The 40.3 million people with a past year SUD represent 14.5% of the population aged 12 or older. The remaining 236.6 million people, 85.5% of the population aged 12 or older, had no past year SUD. But when substances are distinguished as marijuana, methamphetamine, cocaine, stimulants, pain relievers and heroin, the number of people with the respective substance use disorder was as follows. Notice that a significant majority of people with an illicit drug use disorder had a marijuana use disorder.

However, the vast majority of the population did not have a SUD of any kind in the past year. The 40.3 million people with a past year SUD represent 14.5% of the population aged 12 or older. The remaining 236.6 million people, 85.5% of the population aged 12 or older, had no past year SUD. But when substances are distinguished as marijuana, methamphetamine, cocaine, stimulants, pain relievers and heroin, the number of people with the respective substance use disorder was as follows. Notice that a significant majority of people with an illicit drug use disorder had a marijuana use disorder.

Among people aged 12 or older, 5.1% (or 14.2 million people) has a marijuana use disorder in the past year. With people aged 12 or older, .8% (or 2.3 million people) had a prescription pain reliever use disorder; and 6% (or 1.5 million people) had a methamphetamine use disorder. Among people aged 12 or older .5% (or 1.3 million people) had a cocaine use disorder; .6% (or 1.5 million people) had a methamphetamine use disorder; .3% (or 758,000 people) had a prescription stimulant use disorder; and .2% (or 691,000 people) had a heroin use disorder.

Among people aged 12 or older, 5.1% (or 14.2 million people) has a marijuana use disorder in the past year. With people aged 12 or older, .8% (or 2.3 million people) had a prescription pain reliever use disorder; and 6% (or 1.5 million people) had a methamphetamine use disorder. Among people aged 12 or older .5% (or 1.3 million people) had a cocaine use disorder; .6% (or 1.5 million people) had a methamphetamine use disorder; .3% (or 758,000 people) had a prescription stimulant use disorder; and .2% (or 691,000 people) had a heroin use disorder.

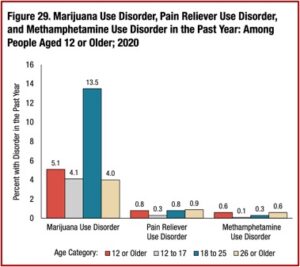

When the use of marijuana, pain relievers and methamphetamines were looked at by age, the percentage of young adults aged 18 to 25 with marijuana use disorder (13.5% or 4.5 million people) was significantly higher than the percentages for adolescents aged 12 to 17 (4.1% or 1.0 million people) or adults 26 or older (4.0% or 8.7 million people). Prescription pain reliever use disorder and methamphetamine use disorder for all three age groups were only nominally different from each other. See the following figure.

There seems to be a clear pattern, particularly among young adults, that beginning marijuana use leads to an increased chance of developing a marijuana use disorder. Data on the perceived risk of harm with the above substances may be one factor explaining where this trend may be headed. Respondents of the 2020 NSDUH survey were asked how much they thought people risk harming themselves physically and in other ways when they used various substances in certain amounts or frequencies.

There seems to be a clear pattern, particularly among young adults, that beginning marijuana use leads to an increased chance of developing a marijuana use disorder. Data on the perceived risk of harm with the above substances may be one factor explaining where this trend may be headed. Respondents of the 2020 NSDUH survey were asked how much they thought people risk harming themselves physically and in other ways when they used various substances in certain amounts or frequencies.

Among people 12 and older, 70.7% of people thought there was a great risk of harm from smoking one or more packs of cigarettes daily, and 68.7% saw great risk from having four or five alcoholic drinks nearly every day. The percentages of people who thought there was a great risk from cocaine or heroin use once or twice a week were 84.7% and 93.2%, respectively. “In contrast, about one fourth of people (27.4%) perceived great risk from smoking marijuana once or twice a week.” See the following figure.

Young adults aged 18 to 25 in 2020 were less likely than adolescents aged 12 to 17 or adults aged 26 or older to perceive great risk of harm from smoking marijuana weekly. Research has identified associations among adults between decreases in perceptions of great risk of harm from smoking marijuana weekly and increases in marijuana use. Nevertheless, people can experience adverse effects from marijuana use, such as marijuana use disorder or injury resulting from operating a motor vehicle while impaired by marijuana. Therefore, it is necessary to educate young adults about adverse effects of marijuana use.

The growth of the marijuana legalization movement will likely lead to increased marijuana use and disorder over all age groups. The 2.8 million first time users of marijuana in 2020, along with the 14.2 million marijuana users who meet the criteria for marijuana use disorder, and the significantly lower perception of there being a risk of harm from smoking marijuana once or twice a week suggest as much. But that isn’t the only concern the NSDUH 2020 hints at. In the near future, I’ll look at other issues present in the data, so return and search for “NSDUH 2020.”

The NSDUH provides information that can be used to support prevention and treatment programs, monitor substance use trends, estimate the need for treatment and inform public health policy. Let’s hope its information on marijuana and other substances is helping to inform public health policy and is used to develop future prevention and treatment programs.