Growing Pains with Narcotics Anonymous

Narcotics Anonymous (NA) rose up from the fragments of an earlier fellowship of the same name that had stopped holding meetings in the fall of 1959. The earlier NA, organized in 1953, struggled and ultimately could not overcome issues stemming from internal dysfunction and personality conflicts. In “Narcotics Anonymous: Its History and Culture,” William White, Chris Budnick and Boyd Pickard said that “NA as we know it today” learned lessons from the dangers of relying on a single dominant leader like Cy M., and of abandoning adherence to the Traditions of NA. They also needed to develop a distinctive culture for it fellowship, one that helped articulate the implications of inserting “our addiction” in the First Step instead of “alcohol.”

One of the first things Jimmy K., Sylvia W., and Penny K. did after rekindling NA meetings at Moorpark in late 1959 was to write new NA-based literature. Who Is an Addict?, What Can I Do?, What Is the NA Program?, Why Are We Here?, and Recovery and Relapse were all written in 1960. We Do Recover was added in 1961. These writings were gathered into a publication also published in 1962 called the Little White Booklet. Personal stories were added in 1966 and the White Booklet served as the center piece of NA literature until the Basic Text, Narcotics Anonymous, was published in 1983. See the NA World Services Recovery Literature page for copies of these and other pamphlets and booklets.

In 1972, NA Trustees looked at the idea of publishing a book similar to AA’s Big Book, but the plan did not get off the ground. It was not until 1977 when Bo S. began to pursue work on the Basic Text with the support of Jimmy K. that the idea became something more than just a thought. “The book was written between 1979 and 1982 over seven World Literature Conferences that involved over 400 recovering addicts in NA. NA’s Basic Text was approved in 1982 and officially released in 1983.”

Following the publication of the Basic Text, NA focused much of its publication efforts on It Works – How and Why, a collection of essays on the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. Just for Today, a book of daily meditations, followed closely afterwards. Further efforts included a workbook on the Steps titled The Step Working Guide and a collection of sponsorship experiences simply called Sponsorship.

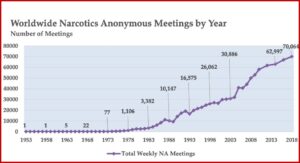

The Basic Text was the first substantial piece of literature created by addicts for addicts, and White, Budnick and Pickard said it marked the beginnings of NA’s own language and culture. NA growth had been progressing before the publication of the Basic Text, but after the release of the Basic Text, NA grew exponentially. There were five meetings by 1964, then 38 meetings in 1971, which grew to 3,382 meetings in 1983. This grew to 10,147 NA meetings by 1988, 16,575 by 1993 and 30,886 by 2003. In 2020, there are an estimated 71,000 NA meetings worldwide. See the following chart taken from “We Do Recover: Scientific Studies on Narcotic Anonymous.”

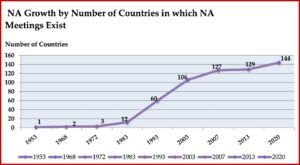

The presence of NA meetings in other countries also grew rapidly after the publication of the Basic Text. By 1968, there was a second country with NA meetings. In 1972, a third country was added and by 1983, there were 12 countries globally with NA meetings. By 1993 there were 60; by 2003, 106; by 2013, 129. There are an estimated 144 countries with NA meetings by 2020. NA literature is now available in 39 languages, with translations into 16 additional languages in process. In 2009, there were more NA meetings being held outside the US than in the US. See the following chart taken from “We Do Recover: Scientific Studies on Narcotic Anonymous.”

The presence of NA meetings in other countries also grew rapidly after the publication of the Basic Text. By 1968, there was a second country with NA meetings. In 1972, a third country was added and by 1983, there were 12 countries globally with NA meetings. By 1993 there were 60; by 2003, 106; by 2013, 129. There are an estimated 144 countries with NA meetings by 2020. NA literature is now available in 39 languages, with translations into 16 additional languages in process. In 2009, there were more NA meetings being held outside the US than in the US. See the following chart taken from “We Do Recover: Scientific Studies on Narcotic Anonymous.” Throughout much of its history, NA was in the shadow of its more well-known parent, AA. NA as we know it today, was founded by “bridge members” of AA (with dual addictions to alcohol and drugs). Its Steps and Traditions were drawn from those found in AA. Meeting formats, use of the Serenity Prayer and the Lord’s Prayer were copied from AA. But in the mid-1980s a large consensus emerged within the program that “challenged NA to step away from AA’s shadow and distinguish itself as a distinct recovery fellowship.” A 1985 communication from NA Trustees entitled, “Some Thoughts on Our Relationship with AA” acknowledged NA’s gratitude to AA. But it also noted its departure from AA in the language of NA’s First Step and then further elaborated on this divergence:

Throughout much of its history, NA was in the shadow of its more well-known parent, AA. NA as we know it today, was founded by “bridge members” of AA (with dual addictions to alcohol and drugs). Its Steps and Traditions were drawn from those found in AA. Meeting formats, use of the Serenity Prayer and the Lord’s Prayer were copied from AA. But in the mid-1980s a large consensus emerged within the program that “challenged NA to step away from AA’s shadow and distinguish itself as a distinct recovery fellowship.” A 1985 communication from NA Trustees entitled, “Some Thoughts on Our Relationship with AA” acknowledged NA’s gratitude to AA. But it also noted its departure from AA in the language of NA’s First Step and then further elaborated on this divergence:

We are powerless over a disease that gets progressively worse when we use any drug. It does not matter what drug was at the center for us when we got here. Any drug use will release our disease all over again… Our steps are uniquely worded to carry this message clearly, so the rest of our language of recovery must be consistent with those steps. Ironically, we cannot mix these fundamental principles with those of our parent fellowship without crippling our own message.

The consensus begun in the 1980s has continued to grow and with it, the use of NA-specific language such as: addiction, self-identification as an addict, clean, and recovery from the disease of addiction. Meeting etiquette, terms and rituals are described in the NA pamphlet An Introduction to NA Meetings. There is an emphasis on solution-focused rather than problem-focused statements. Attention is placed on sustained NA service activity. And most importantly, there are NA members in long-term recovery who stay active in NA rather than disengaging or changing to another fellowship.

In “We Do Recover,” White and others said active drug users typically had a positive view of NA and sought help from NA through a variety of sources including an NA member (49%), referral by a treatment agency (45%) and encouragement from family members (32%). There was a strong association between NA participation and reduced drug use and increased rates of abstinence. The 2018 survey NA members reported an average of 11.4 years of continuous abstinence, with 85% reporting five or more years of stable recovery. But some friction has arisen with NA, and within NA regarding its stand on maintenance medications.

Attitudes and policies of NA towards the use of maintenance medications such as methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone have been a source of tension within the NA fellowship and within the addiction treatment field, where medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is widely considered to be the gold standard treatment approach for opioid use disorder. Table 9 in “We Do Recover” summarized conclusions from various research studies of NA participation among individuals in medication-assisted treatment (MAT). Overall, they suggested NA involvement could be of potential benefit to people during MAT and as a source of post-MAT recovery support. But there are conclusions of a couple studies to take note of here.

Parran et al in “Long-term outcomes of office-based buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance therapy” conducted an 18-48 month follow-up study of opioid-dependent individuals and found that those who were still on buprenorphine/naloxone (bup/nx) at follow-up (85 of 110, 77%) were more likely to report abstinence from opioids and improvement on many quality of life measures. The major reason for discontinuing bup/nx maintenance was repeated evidence of substance use or the “failure to fully adhere with the abstinence based 12-step treatment.” White and others said the primary reason individuals discontinued medication maintenance in the study was the perceived incompatibility between MAT and 12-Step philosophy. But it seems to me another way of understanding why some individuals discontinued MAT was because they found themselves unable to maintain abstinence on MAT. Paran et al said: “Thus improved psychosocial functioning in bup/nx maintained patients was likely due to their marked decreased rate of substance use and not solely due to the bup/nx.”

There certainly is an incompatibility between MAT and NA 12-Step philosophy, but it was not clear if Paran et al tracked NA participation distinct from other 12-Step groups (which includes Methadone Anonymous, established in 1991), as they identified the 12 Step outcome variable as: “AA affiliated.” It was also not clear to me from their discussion if the researchers were even aware of how their blending of all 12 Step attendance into “AA affiliated” failed to distinguish this important nuance.

Monaco et al studied the effects of 12-Step participation on individuals treated for opioid dependence with buprenorphine in “Buprenorphine treatment and 12-step meeting attendance.” They found that despite the potential for philosophical conflicts between 12-Step groups and buprenorphine maintenance treatment (BMT), greater 12-step meeting attendance was associated with superior abstinence outcomes. In the six months after starting treatment, only 14% reported attending 5 or less NA meetings over the previous six months. However, only 33% reported disclosing their BMT status to an NA member. Of the participants who did disclose their BMT status, 26% reported that someone at NA encouraged them to stop taking buprenorphine or decrease their dose.

Qualitative data through semi-structured interviews of participants in the study indicated they were told by some in NA that the use of buprenorphine was a “crutch”; taking buprenorphine meant they weren’t “clean.” The typical view was that genuine clean time cannot be accumulated if you are taking buprenorphine, even if you are otherwise abstaining from all illicit drugs. Monaco et al said this presents a significant barrier for buprenorphine patients who find they benefit from both NA and BMT. But this conclusion failed to consider the historical context within which NA came into being. See “The Birth and Near-Death of Narcotics Anonymous” for more information on the origins of NA.

While this view may be a barrier, Monaco and others failed to acknowledge how buprenorphine has a dependency potential. It is not a neutral substance when it comes to how NA has historically unpacked “our addiction” in its First Step and described “the disease of addiction” in its literature. This means that NA is being implicitly asked to fundamentally blur how it defines being “clean” and confuse what it means by recovery from the disease of addiction. Pointing to the barriers MAT individuals encounter when they attend 12-Step groups and lamenting how they are stigmatized when told they aren’t “clean” (if they continue to use a MAT drug) seems to miss the point. The reality of buprenorphine and methadone as Scheduled substances with a defined abuse or dependency potential has to be acknowledged and addressed, but in most cases is ignored.

However, until that time, there are a couple of strategies identified by Monaco et al that can be used by BMT individuals who find value in attending NA meetings. The first one is to draw a clear, strong distinction between the use of buprenorphine and the abuse of other drugs. “This distinction is primarily based on two properties that separate BMT with substance abuse: 1) understanding buprenorphine medicinally, and 2) specifying the process of taking and acquiring buprenorphine through legitimate (and legal) channels.” Another strategy is to seek out 12-Step groups receptive to MAT, where there are others who take buprenorphine. This provides strength as a collective of similar others. “Despite the potential for philosophical conflicts between 12-step groups and BMT, greater 12-step meeting attendance during the first 6 months of treatment does not precipitate early treatment discontinuation and is associated with superior abstinence outcomes.”

The global expansion of NA has roughly paralleled the rise of the opioid epidemic and the addition of buprenorphine to the MAT arsenal in 2003. These three intertwined circumstances have intensified the debate over medication assisted treatment and recovery and seems to have immobilized our ability to move beyond the debate. Using rhetoric like “crutch” when referring to MAT users or saying the NA member who thinks someone who uses such language is “stigmatizing” perpetuates the polemic split of like-minded individuals into sides of medication haters and medication advocates. Even this distinction has a subtle categorization of individuals into the negative connotation of “haters” and the more sympathetic “advocates.”

William White, one of the coauthors of “Narcotics Anonymous: Its History and Culture” and “We Do Recover,” has tried for a long time to get a dialogue going between the pro-MAT and the anti-MAT groups. In an attempt to create that bridge, he wrote “From Bias to Balance: Further Reflections on Addiction Treatment Medications.” His advice there needs to be heard and acted on: “The key is our ability to objectively portray the potential value and risks of ALL treatment and recovery support options so that affected persons can make informed choices.” He called for rigorous, sustained personal, scientific and clinical investigation. “It also means that any initial distrust of medications from members of recovery communities should be respected by recovery advocates as grounded in the experiential knowledge of those communities.”

I think first there should be an acknowledgement of the value of buprenorphine as a treatment for opioid use disorder. There should be an investigation of its risks in MAT that begins by viewing buprenorphine through the lens of drug-centered action, as articulated by Joanna Moncrieff. Serious, sustained clinical investigation of the possibility of medically supported tapering for buprenorphine needs to be investigated. See the following articles for further interaction with William White’s “From Bias to Balance” and the application of Joanna Moncrieff’s thoughts to buprenorphine assisted recovery: “The Complexities and Limitations of Buprenorphine, Part 1” and “The Complexities and Limitations of Buprenorphine, Part 2.”