Last year The New York Times reported drug overdoses were now the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of fifty. The nationwide total for drug-related deaths was around 64,000 in 2016. According to Vox, this is more than the number of soldiers killed during the entire Vietnam War (an estimated 55,000); more than the 43,000 Americans who died in car crashes at the peak of auto-related deaths in 1972; and more than the 43,000 who died of HIV/AIDS in 1995 at the height of that epidemic. A CDC infographic using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for 2011-2013 reported that individuals who are addicted to opioid painkillers are forty times more likely to be addicted to heroin. Let this last statistic sink in: Today’s heroin addict often begins as someone who first used opioids for pain relief.

In Part 1 of “Doublespeak in the Opioid Crisis” we saw how the misuse of a 1980 letter published in the New England Medical Journal helped to generate these statistics. Here we will look closer at how the accelerated rate in opioid prescribing and one of the players in that increase contributed to the current opioid crisis. Purdue Pharmaceuticals will be shown to have played a crucial role in the birth and growth of the opioid problem in the U.S.

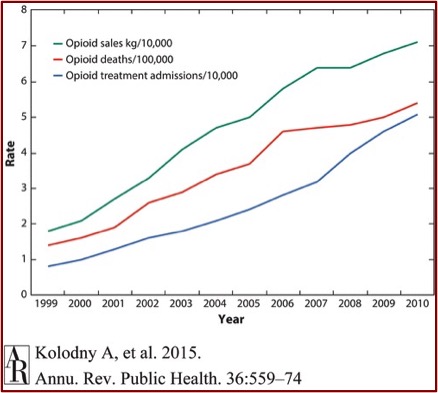

In the Annual Review of Public Health, Kolodny et al. gave the following information in: “The Prescription Opioid and Heroin Crisis.” Since 2000, the consumption of hydrocodone more than doubled and the consumption of oxycodone increased by almost 500%. Parallel to this, the OPR-related overdose death rate increased almost fourfold. Between 1997 and 2011, emergency rooms saw a 900% increase of individuals seeking treatment for addiction to OPRs (opioid pain relievers). “The correlation between opioid sales, OPR-related overdose deaths, and treatment seeking for opioid addiction is striking.” See chart below taken from “The Prescription Opioid and Heroin Crisis.”

In 1986 a paper by Portenov and Foley, “Chronic Use of Opioid Analgesics in Non-Malignant Pain,” concluded that pain patients could be treated safely on a long-term basis with OPRs. “Despite its low-quality evidence, the paper was widely cited to support expanded use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain.” Along with the misquoting and misuse of Hershel Jick’s 1980 letter in the NEMJ, the stage was being set for the coming increase in the prescription and consumption of opioids. The gradual upward trend of opioid use that began in the 1980s accelerated rapidly after the introduction of OxyContin to the OPR market in 1995.

Between 1996 and 2002, Purdue Pharma funded more than 20,000 pain-related educational programs through direct sponsorship or financial grants and launched a multifaceted campaign to encourage long-term use of OPRs for chronic non-cancer pain. As part of this campaign, Purdue provided financial support to the American Pain Society, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the Federation of State Medical Boards, the Joint Commission, pain patient groups, and other organizations. In turn, these groups all advocated for more aggressive identification and treatment of pain, especially use of OPRs.

In 1995 the American Pain Society introduced a campaign entitled: “Pain is the Fifth Vital Sign.” Health care professionals were encouraged to assess pain with the same zeal as they do with other “vital signs”; and become more willing to use opioids to treat non-cancer pain. Before the introduction of OxyContin, physicians were reluctant to prescribe OPRs on a long-term basis for common chronic pain conditions, as they were concerned with their patients developing tolerance, physiological dependence and addiction. Opioid manufacturers, including Purdue, had physician-spokespersons publish papers and give lectures on ‘opiophobia,’ claiming the medical community has been confusing addiction and ‘physical dependence,’ which they said was “clinically unimportant.”

In “The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin,” Art Van Zee said from 1996 to 2001 Purdue conducted more than 40 national pain management and speaker-training conferences at resorts in Florida, Arizona and California. “More than 5,000 physicians, pharmacists, and nurses attended these all-expenses-paid symposia, where they were recruited and trained for Purdue’s national speaker bureau.” In 2001 alone Purdue spent $200 million in a variety of approaches to market and promote OxyContin. Using data on the prescribing patterns of physicians nationwide, Purdue targeted physicians who were the highest prescribers of opioids across the country.

They specifically went after primary care physicians, encouraging a more liberal use of opioids. By 2003, almost half the physicians prescribing OxyContin were primary care physicians. Some experts became concerned that primary care doctors were not sufficiently trained in pain management or addiction issues. Those who worked within a managed care environment of time constraints had the least amount of time to evaluate and follow up on patients with complicated chronic pain.

There was a bonus system in place to encourage sales representatives to increase the sales of OxyContin in their territories. Physicians with high rates of opioid prescriptions received a large number of visits. In 2001, Purdue paid out almost $240 million in sales incentive bonuses to its sales representatives. From 1996 to 2000 Purdue increased its sales force from 318 to 671 sales representatives. The company also had a starter coupon program that provided patients with a 7- to 30-day supply of OxyContin. “By 2001, when the program was ended, approximately 34,000 coupons had been redeemed nationally.”

Branded promotional items like OxyContin fishing hats and stuffed plush toys were distributed. There was even a compact music disc: “Get in the Swing With OxyContin.” The breadth and scope of such marketing was unprecedented for a Schedule II opioid.

Purdue “aggressively” promoted the use of opioids for use in the “non-malignant pain market.” A much larger market than that for cancer-related pain, the non–cancer-related pain market constituted 86% of the total opioid market in 1999. Purdue’s promotion of OxyContin for the treatment of non–cancer-related pain contributed to a nearly tenfold increase in OxyContin prescriptions for this type of pain, from about 670,000 in 1997 to about 6.2 million in 2002, whereas prescriptions for cancer-related pain increased about fourfold during that same period.

Kolodny et al. indicated that in addition to minimizing the risks of OPRs, opioid manufacturers and pain organizations exaggerated the benefits of long-term OPR use. “In fact, high-quality, long-term clinical trials demonstrating the safety and efficacy of OPRs for chronic non-cancer pain have never been conducted.” Surveys of patients with chronic non-cancer pain receiving long-term OPR treatment suggested that most patients continued to experience significant chronic pain and dysfunction. “The CDC and some professional societies now warn clinicians to avoid prescribing OPRs for common chronic conditions.”

Although increased opioid consumption over the past two decades has been driven largely by greater ambulatory use for chronic non-cancer pain, opioid use for acute pain among hospitalized patients has also increased sharply. A recent study found that physicians prescribed opioids in more than 50% of 1.14 million nonsurgical hospital admissions from 2009 to 2010, often in high doses. The Joint Commission’s adoption of the Pain is the Fifth Vital Sign campaign and federally mandated patient satisfaction surveys asking patients to rate how often hospital staff did “everything they could to help you with your pain” are noteworthy, given the association with increased hospital use of OPRs.

Van Zee indicated in “The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin” that a consistent feature in Purdue’s promotion and marketing of OxyContin was a systematic effort to minimize the risk of addiction when using opioids to treat chronic non-cancer-related pain. In the literature and audiotapes of their promotional campaign for physicians, and on its “Partners Against Pain” website, Purdue claimed the risk of addiction from OxyContin was extremely small. Purdue trained its sales force to affirm that the risk of addiction was “less than one percent.” They cited the 1980 NEMJ letter to the editor by Jick (see Part 1 of this article for more information on this) and other studies to minimize the risk of addition. “Misrepresenting the risk of addiction proved costly for Purdue,” to the tune of $634 million in fines:

On May 10, 2007, Purdue Frederick Company Inc, an affiliate of Purdue Pharma, along with 3 company executives, pled guilty to criminal charges of misbranding OxyContin by claiming that it was less addictive and less subject to abuse and diversion than other opioids.

While research showed OxyContin was simply comparable to other available opioids in safety and efficacy, Purdue’s marketing made it into a blockbuster product. Sales escalated from $44 million in 1996 to almost $3 billion over 2001 and 2002. Prescriptions increased from 316,000 to over 14 million.

The remarkable commercial success of OxyContin, however, was stained by increasing rates of abuse and addiction. Drug abusers learned how to simply crush the controlled-release tablet and swallow, inhale, or inject the high-potency opioid for an intense morphine-like high. There had been some precedence for the diversion and abuse of controlled-release opioid preparations. Purdue’s own MS Contin had been abused in the late 1980s in a fashion similar to how OxyContin was later to be; by 1990, MS Contin had become the most abused prescription opioid in one major metropolitan area. Purdue’s own testing in 1995 had demonstrated that 68% of the oxycodone could be extracted from an OxyContin tablet when crushed.

Purdue Pharmaceuticals and its subsidiary companies are privately owned by the Sackler family, named in 2016 by Fortune Magazine as the 19th richest family in the US. None of the Sackler family has even been charged in the past litigation against Purdue. Although family members are not involved in the day-to-day operations of Purdue Pharma companies today, several Sacklers are current board members of Purdue Pharma. In “Meet the Sacklers,” Joann Walters pointed out how the Sackler family has a reputation for its cultural and academic philanthropy to institutions such as Harvard, Yale, MIT, Columbia, Cornell, Stanford and other universities in the US; as well as the Guggenheim Museum, the Smithsonian, the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, the Royal Academy in Britain and others.

Allen Frances said in his article for The Guardian there is no Pablo Escobar Wing at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (there is a Sackler Wing); and no El Chapo Guzman gallery at the Guggenheim (there is a Sackler Center for Art Education). Oxford would no longer be Oxford if it had one of its libraries named in honor of the Cali cartel (but there is a Sackler Library). “The Sackler name is emblazoned on, and disgraces, dozens of the world’s greatest museums, universities, and performing arts centers. So far, none has turned down their donations, none has returned their money already given.” He thought a solution was for institutions to elicit and receive permission from the family members to remove their name, “without any quid pro quo requirement for returned funding.”

I’m not sure about that idea, but I could definitely support two other ones he suggested. First, the family should use its fortune to provide “free treatment for the people they addicted.” Second, they should mount “a reverse marketing campaign to undo their previous brainwashing of doctors and patients.” But I don’t think those ideas will ever happen.

While Purdue announced it halved its sales force and will no longer send out field representatives to promote OxyContin to health professionals in the U.S., there is no indication that the same approach will be taken by its overseas subsidiaries, such as Mundipharma. In “OxyContin Goes Global,” the LA Times noted where a network of international companies owned by the Sackler family are expanding into Latin America, the Middle East, Africa and other regions. “In this global drive, the companies known as Mundipharma, are using some of the same controversial marketing practices that made OxyContin a pharmaceutical blockbuster in the U.S.”

If you’re interested in more information on Purdue Pharma, the Sacklers and OxyContin, also look at: “The Tale of the OxyContin Lie” and “Greed With OxyContin Is NOT Good.”