Bad Things Could Happen with ADHD and the Adderall Shortage

In case you didn’t know, the U.S. has been in the midst of an Adderall shortage since October of 2022 when the FDA announced a shortage of the immediate release formulation. At the time, the FDA said some manufacturers having intermittent manufacturing delays, while others reported they could not meet the increased demand. The agency said it has posted information on the shortage and a list of current manufacturers that are still available, and will continue monitor supply and assist manufacturers “with anything needed to resolve the shortage.” But the shortage problem was still with us.

In case you didn’t know, the U.S. has been in the midst of an Adderall shortage since October of 2022 when the FDA announced a shortage of the immediate release formulation. At the time, the FDA said some manufacturers having intermittent manufacturing delays, while others reported they could not meet the increased demand. The agency said it has posted information on the shortage and a list of current manufacturers that are still available, and will continue monitor supply and assist manufacturers “with anything needed to resolve the shortage.” But the shortage problem was still with us.

Kate Underwood reported in Green Matters that as of June 2023, the FDA’s Drug Shortages still listed Adderall as a current shortage. While manufacturing disruptions are the typical issues leading to drug shortages, other concerns such as increased demand for the drug, and shortages of the active ingredient or supplies can also occur. Additionally, drug manufacturers don’t usually make a single drug. So, increasing the production of a drug in short supply could negatively impact the availability of other drugs made in the same facility.

Writing for Vox, Dylan Scott added another factor to the Adderall shortage—it is a stimulant drug with the potential for misuse or addiction. The DEA lists Adderall and other stimulant-based ADHD medications as Schedule II drugs, meaning they are considered to have the same addictive potential as many opioids. “The fear is that Adderall would follow the same path as opioid painkillers: careless overprescribing would lead to an epidemic of drug addiction — this time, to stimulants.”

One of the active ingredients in Adderall is amphetamine, and therefore the drug is regulated as a controlled substance under federal law. Its potential for abuse has long been recognized, with the cliche example being college students taking the drug to help them study. A 2018 study by federal researchers found that about 5 million Americans misused a prescribed stimulant, of which Adderall is the most common, at least once in the past year; about 400,000 misused stimulant drugs frequently enough to be characterized as having a disorder. (About 2.7 million people in the US report they have an opioid use disorder.)

Medical News Today described the medical uses, side effects and misuse of amphetamines. The opening sentence on the page says, “Amphetamine is a powerful stimulator of the central nervous system. It is used to treat some medical conditions, but is also highly addictive, with a history of abuse.” Amphetamines are used today to treat ADHD. In the past it has been used to treat narcolepsy, but concerns with side effects have led to it being increasingly replaced by modafinil.

Physical side effects can include low or high blood pressure, erectile dysfunction, rapid heart rate, blurred vision, dry mouth, tics, nosebleed, and others. Psychological effects may include apprehension, anxiety, irritability and restlessness, mood swings, insomnia, obsessive behaviors and grandiosity, or an exaggerated sense of one’s own importance. “In rare cases, psychosis may occur.”

When used as a recreational drug it can speed up reaction times, increase muscle strength and reduce fatigue. A methamphetamine called Pervitin was used by Hitler’s forces for these benefits during WW II; see “Repeating Past Mistakes.”

The DEA Drug Fact Sheet said the following about amphetamines:

The effects of amphetamines are similar to cocaine, but their onset is slower and their duration is longer. In contrast to cocaine, which is quickly removed from the brain and is almost completely metabolized, methamphetamine remains in the central nervous system longer, and a larger percentage of the drug remains unchanged in the body, producing prolonged stimulant effects.

Chronic abuse produces a psychosis that resembles schizophrenia and is characterized by paranoia, picking at the skin, preoccupation with one’s own thoughts, and auditory and visual hallucinations. Violent and erratic behavior is frequently seen among chronic users of amphetamines.

In order to mitigate the potential for abuse, the DEA sets production limits for the manufacturers of Adderall and its generic competitors. In 2019 the DEA announced it was permitting more production of Adderall, but we still don’t know exactly how much production has been authorized or what limits have been set for individual companies. “We don’t know which company gets how much.” Some companies say they are short, but the DEA replies they haven’t used all their supply, so there’s back-and-forth finger-pointing going on. Listen to the On Point program, “What’s behind the ADHD drug shortage” to hear more discussion of this issue.

However, there also seems to a problem that stems from the opioid crisis. In 2021 there was a settlement with the three largest drug distributors that “flag and sometimes block” pharmacies’ orders of controlled substances like Adderall when they exceed a certain threshold. Bloomberg reported that pharmacists said it restricts their ability to fill many different types of controlled substances in addition to opioids. The rules force some independent pharmacists to use creative workarounds. “Sometimes, they must send patients on frustrating journeys to find pharmacies that haven’t yet exceeded their caps in order to buy prescribed medicines.”

This was illustrated in an article for STAT, written by a “biopharma supply chain specialist” who can’t find the Adderall she’s prescribed. She said she’s been using Adderall for ten years to help her function. Then in February of 2023, she was unable to fill her prescription at the pharmacy down the street. She finally was able to fill it at the 20th pharmacy she called, although it meant a 50-minute drive. She recommended several steps to increase the transparency in the supply chain of Adderall. “This will foster efficiency, reliability, and the ability to identify potential risks before they spiral out of control, as has happened now with not just Adderall but other ADHD medications.”

Money making considerations are also involved in the Adderall shortage. Vox reported that after Adderall was approved in 1996, it quickly became the most commonly prescribed treatment for ADHD, although Ritalin and other drugs are still used. PsychCentral listed Adderall as the fourth most prescribed psychiatric medications, with 26.24 million prescriptions in 2020. Other medications prescribed to treat ADHD within the top 25 most prescribed drugs included: Concerta (10th), Vyvanse (20th), and Focalin (24th). Three of the most expensive medications, making the most money for their manufacturers were Concerta ($3.28 billion), Vyvanse ($3.01 billion), and Adderall ($2.35 billion). ADHD prescriptions accounted for over a third of the prescriptions in 2020.

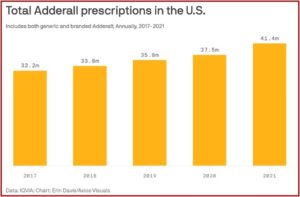

Axios reported some different statistics for both generic and branded Adderall prescriptions, according to IQVIA, a health research firm. Since 2017, IQVIA reported Adderall prescriptions rose from 32.2 million to 41.4 million. This was up more than 10% from 2020. See the following graph taken from the Axios article.

Axios said prescriptions skyrocketed as it became significantly easier to get a diagnosis of ADHD and a prescription for Adderall during the pandemic. A wave of telemedicine startups emerged on TikTok and Instagram, suggesting people should look into ADHD medication if they felt distracted. The Wall Street Journal reported some startups diagnosed people with ADHD and prescribed stimulants after 30-minute video calls — “entirely remotely, and much faster than a typical diagnosis from an in-person psychiatrist.” The trouble with rapid diagnoses is it can be difficult to tell whether the problem is actually ADHD. “Anxiety can present as ADHD, and depression can present as ADHD.”

This spike in diagnoses raises questions about whether ADHD is being over-diagnosed, but that’s really a question that predates the pandemic. See (“The Tip of the ADHD Iceberg” and “National ADHD Epidemic”) for more information. If supply can’t keep up with demand, experts are warning we could have a public health crisis. Even worse, we could face another movement of people from the pharmaceutical market to the illicit drug market, as what happened with opioids. Leo Beletsky, an epidemiologist at Northwestern University said, “Lots of bad things can happen. … Conditions are very much ripe for that to happen here.”

Overdiagnosis of ADHD

In “Twenty-Year Trend in Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder”, Xu et al estimated the prevalence of diagnosed ADHD among US children and adolescents from 1997 to 2016. They estimated the prevalence of diagnosed ADHD among US children and adolescents was 10.2% in 2016. There was a consistent upward trend across subgroups by age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, and geographic regions. “These findings indicate a continuous increase in the prevalence of diagnosed ADHD among US children and adolescents.” They said the common perception that ADHD overdiagnosed in the US was not supported by the scientific evidence. But that is not the end of the matter.

A 2021 study by Kazda et al, “Overdiagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents” said that questioning the appropriateness of ADHD diagnosis has grown along with the diagnosis rates. They acknowledged that disagreement continues about how much of the increased diagnoses can be attributed to true increases in frequency, improved detection or diagnostic inflation because of misdiagnosis and/or overdiagnosis. They systematically reviewed the research literature to identify and appraise any evidence of overdiagnosis of ADHD in children and adolescents. They found evidence of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of ADHD.

Of the 12,267 potentially relevant studies retrieved, 334 (2.7%) were included. Of the 334 studies, 61 (18.3%) were secondary and 273 (81.7%) were primary research articles. Substantial evidence of a reservoir of ADHD was found in 104 studies, providing a potential for diagnoses to increase (question 1). Evidence that actual ADHD diagnosis had increased was found in 45 studies (question 2). Twenty-five studies showed that these additional cases may be on the milder end of the ADHD spectrum (question 3), and 83 studies showed that pharmacological treatment of ADHD was increasing (question 4). A total of 151 studies reported on outcomes of diagnosis and pharmacological treatment (question 5). However, only 5 studies evaluated the critical issue of benefits and harms among the additional, milder cases. These studies supported a hypothesis of diminishing returns in which the harms may outweigh the benefits for youths with milder symptoms.

They recommended that practitioners, parents and teachers carefully weigh the potential benefits and harms that can go along with ADHD diagnosis and treatment, particularly when individuals with milder symptoms are identified. “For this group, the benefits of diagnosis and treatment may be considerably reduced or outweighed by harms.”

In his review of the study for Mad in America, Peter Simons said “Each [of the 334 included studies] provided data on at least one of the five conditions. They found that all five conditions were supported by the research.” There was also significant evidence of harm after diagnosis, including how a biomedical view of difficulties was associated with disempowerment. He said the researchers warned that diagnosis “can also deflect from other underlying individual, social, or systemic problems.”

Because there is no biological test for ADHD, and the diagnosis is applied subjectively across age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status, there is room for the diagnosis to expand. Additionally, as the diagnostic criteria are loosened, rates of ADHD have increased. The researchers confirmed that a large proportion of the new cases are on the “mild” end of the spectrum. Rates of stimulant treatment for ADHD have also increased, including those with “mild” or “subclinical” ADHD.

In his book, Saving Normal, Allen Frances, a psychiatrist and the former chair for the DSM-IV, said in retrospect, he wishes there had been cautions in the DSM-IV about overdiagnosis and tips to avoid it. He thought they missed the boat. “No one dreamed that drug company advertising would explode three years after the publication of the DSM-IV or that there would be the huge epidemics of ADHD, autism, and bipolar disorder—and therefore no one felt any urgency to prevent them.” For more on the DSM and overdiagnosis, see “Guild Interests Behind DSM Diagnosis.”

The Demedicalization of ADHD

Not only does it seem ADHD is overdiagnosed, there are some researchers who question whether the diagnosis of ADHD meets the criteria for a disorder set out in the manual used by the medical and psychiatric fields. Freedman and Honkasilta argued that the definition of ADHD relies on subjective cultural values to define “abnormal” behavior. Reviewing their study for Mad in America, Peter Simons said, “The diagnosis thus fails to meet the criteria, as stated in the DSM, that disorders must not be reducible to behavior that violates social norms.” The researchers argued that ADHD should be demedicalized and removed from the DSM, like homosexuality was in 1980.

The British Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist Sami Timimi said in his 2017 article, “Non-diagnostic based approaches to helping children who could be labeled ADHD and their families” that it required little intellectual effort to conclude that the concept and definition of ADHD “is replete with problems around reliability and validity.” The diagnostic guidelines note how ADHD behaviors may be minimal or absent in several settings. These include when the person in under close supervision, engaged in an activity that is particularly interesting to them or in a new, novel setting. Even if a genetic basis for ADHD were found, we’d still have to ask why such behaviors should be treated as disorder rather than differences. “Deciding where to draw the line between what we consider part of the “ordinary” spectrum of behaviours and what we decide is “pathological” is more dependent on cultural than scientific processes.”

He said if he asked the question, “what is ADHD?”, it is not possible for him to reply by referring to a particular known pathological abnormality. Instead, he would have to provide a description ADHD as the presence behaviors like of hyperactivity, impulsivity and poor attention. This was contrasted with answering the question, “what is diabetes?” “Diagnosis in that context sits in a “technical” explanatory framework. In psychiatry what we are calling diagnosis (such as ADHD) will only describe but is unable to explain.”

Timimi concluded that ADHD is then not a medical diagnosis, but rather a descriptive classification. And since it is not a medical diagnosis, “it is not surprising that there has been a failure to find any specific and/or characteristic biological abnormality such as characteristic neuroanatomical, genetic or neurotransmitter abnormalities.” He thought the idea of ADHD as a medical diagnosis was past its use-by date and should be discarded.

ADHD is a cultural construct. It is often argued that the use of categorical constructs like ADHD enables the study of aetiology, treatment and prognosis. Evidence outlined above demonstrates that far from enabling any advancement of knowledge or clinical practice, it has created an illusion of progress and resulted in exposure of possibly millions of children and young people to unnecessary and potentially harmful medications. It has spurred on liberal use of stimulant medication, despite the lack of evidence for improved long term outcomes resulting from this.

We are not at the cultural crossroads with ADHD today that we were with homosexuality in 1980. ADHD will likely continue to be a diagnosable disorder. Yet serious consideration of the above discussion of its overdiagnosis, its future demedicalization and removal from the DSM as a disorder and the lack of improvement in long-term outcomes of individuals taking ADHD prescribed stimulants should be done. In retrospect, the Adderall shortage may not truly be the serious public health crisis that is getting all the press coverage. But if it leads people from the pharmaceutical market to the illicit drug market in search of their amphetamines to help them function, like the person in the STAT article, “Lots of bad things can happen.”