The Eye of the Beholder with Psychedelic Therapy

Classical psychedelic drugs such as psilocybin, LSD, and mescaline were used and researched regularly in psychiatry before they were placed in Schedule I of the UN Convention in 1967 and in Schedule I of the US Controlled Substances Act in 1970. These actions legally defined these psychedelics as having no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Without a clinical focus and the widespread use of LSD within the 1960s counterculture movement, research rapidly dwindled. But there has been a resurgence of clinical research interest in the use of psychedelics for psychiatric disorders such as major depression, PTSD, anxiety and addiction.

In “Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs,” Rucker, Iliff and Nutt described clinical trials using psychedelics pre and post prohibition. They also discussed the methodological challenges of preforming good quality clinical trials, and suggested an approach to the existing legal and regulatory barriers to licensing psychedelics as a treatment in mainstream psychiatry.

Experimentation and clinical trials undertaken prior to legal sanction suggest that they are not helpful for those with established psychotic disorders and should be avoided in those liable to develop them. However, those with so-called ‘psychoneurotic’ disorders sometimes benefited considerably from their tendency to ‘loosen’ otherwise fixed, maladaptive patterns of cognition and behaviour, particularly when given in a supportive, therapeutic setting. Pre-prohibition studies in this area were sub-optimal, although a recent systematic review in unipolar mood disorder and a meta-analysis in alcoholism have both suggested efficacy. The incidence of serious adverse events appears to be low.

The term ‘psychedelic’ was coined by Humphry Osmond in a letter he wrote to Aldous Huxley in 1956. Osmond combined two ancient Greek words, psyché, meaning soul or mind; and delein, meaning to reveal. So psychedelic means ‘soul revealing.’ The earliest direct evidence for the use of psychotropic plants dates to around 3700 BC in the northeastern region of Mexico. Carbon-dated buttons of peyote and red beans containing mescaline were found in caves used by humans for habitation. Arthur Heffter isolated mescaline from the peyote cactus in 1897.

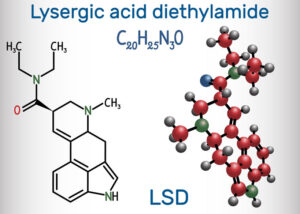

Albert Hofmann first synthesized LSD in 1938. Coming at a time before there were effective medicinal therapies, the discovery of LSD was of interest to psychiatry. Acute LSD intoxication appeared to mimic some of the symptoms of acute psychosis and drew the research interest of Humphry Osmond. There also seemed to be an increased awareness of repressed memories and other elements of the subconscious, which suggested it could be helpful in psychotherapy. Trials in depressive, anxious, obsessive and addictive disorders in conjunction with psychologically supportive contexts reinforced that view. “By the end of the 1960s, hundreds of papers described the use of mescaline, psilocybin and (most frequently) LSD in a wide variety of clinical populations with non-psychotic mental health problems.”

The widespread use of LSD outside of the carefully orchestrated clinical and research settings and the growing reports of adverse effects when under the influence of LSD and other psychedelics led to prohibition. Medical use stopped quickly when doctors could no longer prescribe it. The following graph taken from “Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs” depicts how the annual number of publications listed in PubMed rapidly decreased after 1968.

Recently, there have been several studies and randomized controlled trials using psychedelics with various nonpsychotic disorders. In “LSD: can psychedelics treat mental illness?,” written by Anya Borrissova for the Mental Elf blog, Borissova reviewed the findings of Fuentes et al, “Therapeutic Use of LSD in Psychiatry.” This was a systematic review of randomized-controlled clinical trials with LSD. The authors identified 11 studies that met their inclusion criteria: randomized controlled trials of LSD that involved patients with a mental illness diagnosis. The qualities of the studies was scored with the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Assessment tool.

Seven of the 11 trials had recruited individuals diagnosed with what is now referred to as alcohol use disorder (AUD), 1 for AUD or neurotic diagnosis, 1 for heroin use disorder, 1 for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases, and 1 with a neurotic diagnosis (depression, anxiety). The publication dates ranged from 1966 to 2014, which covered several changes in how mental disorders were labeled by the four different editions of the DSM, the 2nd through the 5th. The majority of the studies had a low risk of selection, attrition detection and reporting bias, as measured by the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Assessment tool. However, five of the studies had a high risk of bias due to blinding.

With the studies of alcohol use disorder, a significant effect of LSD was observed in four studies. “However, this effect was related to quality of life and general health in some of the studies, with no clear improvements in alcohol abstinence.” While there was a substantial improvement in total abstinence for the LSD group, there were not significant differences in the global adjustment scale. With regard to the two studies of neurotic symptoms, one study showed statistically significant improvement in symptoms at 6-8 weeks in most measurements. But it failed to reach statistical significance in six months, although all groups showed significant differences in a large number of variables. Fuentes et al concluded that LSD was a potential therapeutic agent in psychiatry; with the strongest evidence for its use in treating alcoholism.

Borissova said the heterogeneity of the studies did not allow for a meta-analysis, which made it difficult to draw firm conclusions. The earlier studies had different methodologies than what is used now, which limits the application of the results to modern research. The use of the gold standard of the double-blind methodology with psychedelics is extremely difficult, if not impossible to achieve, and five studies had a high risk of bias for blinding. The psychiatric diagnostic categories were also different in studies done over such a wide range of time. How the studies defined their ‘control group’ varied, with those that failed to use an active placebo having questionable validity.

When discussing the implications of Fuentes et al, she said LSD generally appears to be safe and potentially effective. The lack of consistency between the studies may have limited their ability to find an LSD effect. “On the basis of this review, we cannot conclude that there is strong evidence of positive effects.” She did think change in scheduling the drugs to allow for easier research into LSD was justified. Tellingly, she ended with this caution: “Psychedelic research inspires a lot of excitement; the danger is that this turns into hype.”

There has been a growing interest in psychedelics as an agent for reaching peak experiences, for self-care or wellness, and as an instrument of therapeutic change. Michael Pollan explored this psychedelic ‘renaissance’ in his 2018 best-selling book, How to Change Your Mind. In a New York Times article, he said now when you leave the airport in Quito, Ecuador, there are people with signs that say: ‘ayahuasca ceremony’ instead of ‘taxi.’ “These people became shamans, like last week. People are getting hurt.” He had positive things to say about his experiences with psilocybin, but cautioned against legalization: “Psilocybin has a lot of potential as medicine, but we don’t know enough about it yet to legalize it.”

The promise of pre-prohibition LSD and psychedelic studies and their potential as therapeutic agents has to be replicated within a modern, controlled context. A 2016 paper by Rucker with different researchers than those cited above, “Psychedelics In the Treatment of Unipolar Mood Disorders,” elaborated on some of the difficulties inherent in designing trials with psychedelics. Blinding is largely impossible. Therapeutic doses of psychedelics produce subjective and objective changes in thinking, feeling and behavior that are usually obvious to both the participant in the study and the observer. Because of this, placebo control is problematic because the absence of the psychedelic effect is obvious. The ‘set’ (psychological state) and ‘setting’ (the interpersonal and physical environment) within which the drug is experienced are inextricably linked to the therapeutic effect.

It appears that a particularly careful and well-considered balance between the needs of the participants and the needs of the trial will be required in studies using psychedelics. . . Trial designers will need, similarly, to be detailed and explicit about the environmental and psychotherapeutic milieu in which a study is to be performed. Clinical trials using psychedelics will need to be sufficiently methodologically detailed at the point of publication to allow genuine replication. Scientific mechanism studies will need, ideally, to be pursued alongside clinical trials if this is pragmatic and ethical. Within this multi-pronged approach to evidence gathering, and a sufficient degree of definition, replicable results and common threads of insight into the nature and applicability of psychedelics to medicine in general, and to psychiatry in particular, should emerge with time.

In “Psychedelics In the Treatment of Unipolar Mood Disorders,” Rucker et al referred to and quoted Rick Strassman’s 1984 literature review, “Adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs.” Strassman noted that the description and reporting of adverse reactions to psychedelics was subject to the investigators’ attitudes towards psychedelics.

With the available data, it appears that the incidence of adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs is low when individuals, both normal volunteers and patients, are carefully screened and prepared, supervised and followed up, and given judicious doses of pharmaceutical quality drug. The few prospective studies noting adverse reactions have fairly consistently described characteristics predicting poor response to these drugs. The majority of studies of adverse reactions, retrospective in nature, have described a constellation of premorbid characteristics in individuals seeking treatment for these reactions where drugs of unknown purity were taken in unsupervised settings.

The authors repeated an assessment of the perceived psychotherapeutic mechanism identified by Betty Eisner and Sidney Cohen in their 1958 article, “Psychotherapy with Lysergic Acid Diethylamide.” Eisner and Cohen said their review of the existing literature in 1958 suggested that 1) LSD lessened defensiveness; 2) there was a heightened capacity to relive early experiences with accompanying release of feelings; 3) therapist-patient relationships were enhanced; 4) there was an increased appearance of unconscious material. Eisner and Cohen went on to describe their exploration of the therapeutic possibilities of LSD with 22 patients with diagnoses ranging from neurotic depression, anxiety, character disorder, borderline personality and schizophrenia. Improvement was noted in 16 of 22 cases, where improvement was judged as continued success in behavioral adaptation.

Rucker et al concluded that psychedelic therapy may represent a kind of “catalyzed psychotherapy,” where the psychedelic drug hastens the breakdown of entrenched, maladaptive ways of thinking and behavior in supportive environments. While the evidence from pre-prohibition literature is unsystematic and methodologically inadequate, it suggests further research is worth doing. But there are limitations to the future research of psychedelic psychotherapy that researchers need to be aware.

As discussed above, it is essentially impossible to develop a double-blind methodology with psychedelics because of the unique characteristics of the drugs. This opens investigations into psychedelic therapy to the potential bias of the researchers—one that cannot be eliminated. Strassman raised this warning in Rucker et al, where he was quoted as saying it is important to use caution when discussing the idea of adverse reactions to psychedelic drugs. Whether the researcher views the drug-induced state as a pathological one, or as trying to reach a “higher” level of consciousness, “The description and/or reporting of adverse reactions to psychedelics is, therefore, subject to some degree of investigators’ perspective on the use of these drugs.”

Given the potential bias of researchers into psychedelic therapy and the current inability of medical research to neutralize it, caution when interpreting the conclusions of any research is necessary. As Anya Borissova said, although psychedelic research inspires a lot of excitement; “the danger is that this turns into hype.” This danger cuts both ways, whether a particular researcher sees the drug-induced state as a pathological one, or as an attempt to reach a “higher” level of consciousness. At the very least, it seems researchers should declare any personal bias with regard to psychedelics within any written or published research into psychedelic therapy.

As an illustration, does knowing that Betty Eisner and Sidney Cohen both personally used LSD at least once (and probably more than just once) alter your assessment of their endorsement of psychedelic therapy? It was 1958 and their failure to do so is not an ethical misstep, but that awareness added to the inability to adequately blind their research should lead to some reservations with their conclusions endorsing psychedelics. Michael Pollan acknowledged the concern of potential bias in psychedelic research:

Western science and modern drug testing depend on the ability to isolate a single variable, but it isn’t clear the effects of a psychedelic drug can ever be isolated, whether from the context in which it is administered, the presence of the therapists involved, or the volunteer’s expectations. Any of these factors can muddy the waters of causality. And how is Western medicine to evaluate a psychiatric drug that appears to work not by means of any strictly pharmacological effect but by administering a certain kind of experience in the minds of the people who take it?

It seems impossible for psychedelic psychotherapy to be separated from its set or setting; and for research into its effectiveness to be reliably evaluated by a double blinded research methodology. The effectiveness (or not) of psychedelic therapy will necessarily be in the eye of the researcher and beholder.

For more on Betty Eisner, Sidney Cohen and early LSD research look, see: “Bill W. and His LSD Experiences.”

Originally posted on October 13, 2020.