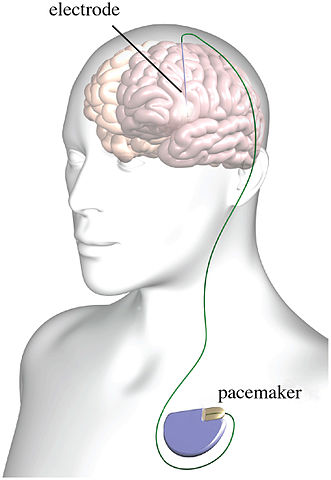

graphic of deep brain stimulation; licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

Psychiatry has had a fascination with electricity-based treatments beyond the more well-known procedure of ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). Not only is there transcranial electrical stimulation (TES), there is also transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), deep brain stimulation (DBS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and several other examples of electrical brain stimulation (EBS). But there are multiple issues with EBS techniques and devices. These concerns include the inability of TES to target neuronal networks as claimed, questionable science and reproducibility problems and the potential to hack implantable medical devices (IMDs).

TES is a non-invasive method used to treat conditions ranging from seizures to depression. TES is different from ECT, as TES involves a less powerful electrical current and is not intended to induce a seizure. “The procedure involves placing electrodes on the scalp in order to send an electric current through the head.” Proponents of TES say they can target specific neuronal networks and induce activation.

However researchers at the University of Szeged in Hungary found that 75% of the scalp-applied current of TES was weakened by soft tissue and the skull before reaching the brain. As Peter Simons noted in his summary of the Hungarian TES research, this means most of the electric field does not have the specific targeted effect on neurons claimed by other researchers since “most of the electricity does not even reach the brain.” In order to directly impact brain circuits, the electrical current would have to be four to six times higher. Electrical stimulation of the scalp can affect brain activity in multiple indirect ways, according to the researchers. However, “there is no accepted theory to explain how TES affects neuronal circuits in the brain, mainly because the physiological mechanisms of TES are not well understood.”

A review of the evidence for TES or cranial electrical stimulation (CES) did not find sufficient evidence to support it having clinically important effects on fibromyalgia, headache, neuromusculoskeletal pain, degenerative joint pain, depression, or insomnia. There is some low-strength evidence of a modest benefit in patients with anxiety and depression. But the research has methodological problems and is of such poor quality, that its conclusions are questionable. “When TES was compared with treatment as usual, even these poor quality studies found no significant difference.”

Indeed, the research on the supposed brain effects found by other studies is plagued by poor methodology. The current researchers argue that other studies, which purport to find neural effects, test for effects at the same frequency as the intervention—meaning that any supposed effects are more likely due to the ongoing external electric field, not actual changes in neural circuits.

Heroux et al. wrote of the “Questionable Science and Reproducibility in EBS Research.” In order to investigate whether the positive results for EBS that dominates the published literature was reflected in the experience of researchers using EBS, they invited 976 researchers to complete an online survey. They also audited 100 randomly-selected published EBS papers. “Only 40–55% of survey respondents were able to routinely reproduce previously published results. Worrisome was the finding that researchers engaged in, but failed to report, questionable research practices.”

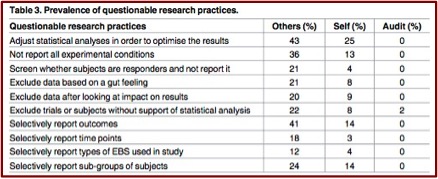

When asked about questionable research practices, survey respondents were aware of other researchers who adjusted statistical analysis to optimize results (43%) and selectively reported study outcomes (41%) and experimental conditions (36%) (Table 3). About 20% of respondents knew researchers who engaged in other shady practices (Table 3). Fewer respondents admitted to engaging in these practices themselves (Table 3), although 25% admitted to adjusting statistical analysis to optimize results. [Table 3 appears below]

Almost al of the respondents (92%) said these questionable practices should be disclosed in the published research papers themselves. However, as Table 3 showed, only 2 of the audited research papers admitted to any questionable practices. “Furthermore, 90% of audited papers reported positive primary findings, i.e. publication bias, and 30% interpreted p-values between 0.05 and 0.1 as statistical trends or statistically significant, i.e. spin.” Several researchers voiced concerns about EBS research, as sampled below.

Almost al of the respondents (92%) said these questionable practices should be disclosed in the published research papers themselves. However, as Table 3 showed, only 2 of the audited research papers admitted to any questionable practices. “Furthermore, 90% of audited papers reported positive primary findings, i.e. publication bias, and 30% interpreted p-values between 0.05 and 0.1 as statistical trends or statistically significant, i.e. spin.” Several researchers voiced concerns about EBS research, as sampled below.

I think there is a huge publication bias in this field and, in my opinion, the positive results of tDCS are highly overestimated. There does seem to be a suspiciously large number of positive tDCS trials published, and in almost any discipline it has been used in.”Although the consensus within publications in that electrical stimulation works well and is reliable, my experience of talking to other researchers at conferences and within my department suggests that there is a huge amount of unpublished, unsuccessful attempts at using the stimulation. Many of which have no clear methodological issues.

Heroux et al. speculated the lack of transparency and scientific rigor was likely due to the pressure on researchers to publish significant results in high impact journals. This pressure creates a vicious cycle where journals, institutions and funding agencies expect significance. In order to survive and meet these expectations, scientists consciously or unconsciously adopt “questionable or fraudulent research practices.” Although these pressures are not unique to research into EBS, they taint the efforts of researchers genuinely trying to improve brain function. “The clinical promise of EBS will remain illusory until the practice of neuroscience becomes more open and robust.”

Danielle Egan wrote an in depth article for Mad in America about The Broaden Trial, one of the largest clinical trials to investigate the efficacy of DBS for depression. It was terminated in 2013 because of a low (17%) success rate among at least 75 patients that received the implant. This was Egan’s second article on the Broaden Trial for Mad in America. See “Deep Brain Problems” for a discussion of DBS and the Broaden Trial as well as Egan’s first article. The British journal Lancet finally published a paper on the results of the trial in October of 2017.

The Broaden Trial ultimately signed up 201 patients. But the FDA required a futility analysis of “at least 75” of the initial implanted patients at the six-month mark. The Lancet paper revealed that 90 patients were implanted between 2008 and 2013, and their data analysis revealed an estimated success rate of only 17%—much lower than the 78% response rate initially advertised in June 2008, soon after the Broaden trial began and SJM began to solicit patients. In late 2013, SJM decided to terminate the trial, even though the results were still slightly higher than the FDA’s definition of futility: a 10% success rate. By that point, the trial had been going on for almost five years, collecting follow-up data that is detailed below.

The published reports said at the end of two years, two-thirds of those who stayed in the study were helped. “But this efficacy only showed up in the open-label part of the trial, and not during the placebo-controlled phase, when the investigators were ‘blinded’ to who was getting the treatment.” While the published paper said there were no side effects associated with DBS programming, Egan reported that all five of the patients she interviewed who participated in the Broaden Trial said they experienced programming-related adverse effects. The Broaden paper also had a tendency to attribute serious adverse effects like suicidality in the study’s participants to their underlying mood disorder and not to the device or active stimulation. “Two people in the study died by suicide. Both were in the control group, but they committed suicide after they started receiving stimulation.”

You can read a further critique of DBS in James Coyne’s article, “Deep Brain Stimulation: Unproven Treatment” for PLOS Blogs. His concluding comments contained the following:

So, we have a heavily hyped unproven treatment for which the only clinical trials have either been null or terminated following a futility analysis. Helen Mayberg, a patent holder associated with one of these trials was inappropriate to be recruited for commentary on another, more modestly sized trial that also ran into numerous difficulties that can be taken to suggest it was premature. However, I find it outrageous that so little effort has been made to correct the record concerning her BROADEN trial or even to acknowledge its closing in the JAMA: Psychiatry commentary. Untold numbers of depressed patients who don’t get expected benefits from available treatments are being misled with false hope from anecdotes and statistics from a trial that was ultimately terminated.

Lastly, there is a research article showing how implantable medical devices (IMDs), like that used for DBS, could be hacked. “Securing Wireless Neurotransmitters,” by Marin et al., described how they reverse engineered an IMD and conducted several software radio-based attacks that could compromise the safety and privacy of patients. They demonstrated that reverse engineering was possible without having physical access to the devices.

We conducted several software radio-based attacks that could endanger the patients’ safety or compromise their privacy, and showed that these attacks can be performed using inexpensive hardware devices. The main lesson to be learned is that security-through-obscurity is always a dangerous design approach that often conceals insecure designs. IMD manufacturers should migrate from weak closed proprietary solutions to open and thoroughly evaluated security solutions and use them according to the guidelines.

Since December of 2017 the FDA has approved two DBS medical devices to treat epilepsy (Medtronic DBS System for Epilepsy) and Parkinson’s (Vercise Deep Brain Stimulation System). But as James Coyne noted, this is “a heavily hyped unproven treatment for which the only clinical trials have either been null or terminated following a futility analysis.” The physiological mechanisms of transcranial electrical stimulation (TES) are not well understood and “there is no accepted theory to explain how TES affects neuronal circuits in the brain.” And it doesn’t deliver the current it says it does to the brain; four to six times the voltage of current TES treatment was needed to get a direct effect on the brain.

I think the ultimate concern with electrical brain stimulation (EBS) is that even the researchers who work in the field acknowledge the positive results in the published literature can’t be trusted. More time and reliably replicated studies are needed before psychiatry starts extolling the merits of EBS treatment any further. And it would be nice at least have the beginnings of a consensus of agreement on exactly how EBS works before psychiatry turns it loose on a population desperate for the relief it promises.