The Future of Marijuana Legalization in Pennsylvania

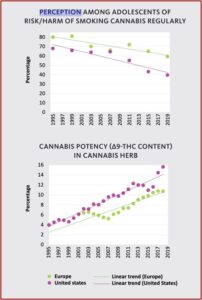

The World Drug Report for 2021 reported that roughly 200 million people used cannabis in 2019, roughly 4% of the global population. North America has the highest number of cannabis users, with an estimated 14.5% of its population use in 2019. The percentage of THC (∆9-THC), the main psychoactive ingredient in cannabis, rose from around 4% in 1995 to 16% in 2019. Although THC is responsible for the development of mental health disorders in long-term, heavy cannabis users, the percentage of adolescents who view regular cannabis use as harmful has decreased by as much as 40% during the same time period. While the potency of cannabis has increased four-fold since 1995, fewer young people see it as harmful.

Such a mismatch between the perception and the reality of the risk posed by more potent cannabis could increase the negative impact of the drug on young generations. Scientific evidence has demonstrated the harm to health caused by regular use of cannabis, particularly in young people. Evidence from surveys suggests a link between a low perception of risk and higher rates of usage. This is the case not only in Europe and the United States, but also in other parts of the world.Aggressive marketing of cannabis products with a high Δ9-THC content by private firms and promotion through social-media channels can make the problem worse. Products now on sale include cannabis flower, pre-rolled joints, vaporizers, concentrates and edibles. The potency of those products varies and can be unpredictable – some jurisdictions where cannabis use is legalized set no limit on THC content – and may be a public health concern.

(See the following charts from the World Drug Report for 2021)

In 2020, 14.6% of high-school students reported past-month use of cannabis. There was a significant increase in the daily or near-daily use of cannabis in the past two years (20919 and 2020). The daily or near-daily use of marijuana was estimated at 4.1% among high-school students in 2020, compared with almost 1% in 1991. In the past few years, the debate about medical marijuana and measures allowing for the non-medical use of cannabis in the United States have led adolescents to perceive cannabis as less harmful than was true in the past.

In the United States, the decreasing perception of risk from occasional or regular use of cannabis is considered to be a spillover effect as debates over measures allowing the medical and non-medical use of cannabis in the states considering those measures extend to other states, and the result of an increase in regular cannabis use, which comes to be perceived as less risky among users, as well as media coverage of the medical use of various cannabis products in many states containing claims of the medical benefits of cannabis products, including those of CBD.

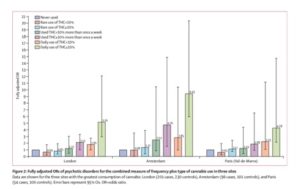

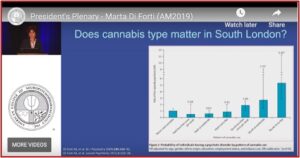

Not only are there concerns for increases in mental health disorders among youth, there are other concerns with how cannabis effects young adults. Cannabis use among adolescents was found to be related to impaired cognition; showing delayed effects on self-control, working memory and concurrent effects on delayed memory recall and perceptual reasoning (ability to think and reason using pictures or visual information). So, exactly what are the risks when individuals, particularly adolescents and young adults, use marijuana? A meta-analysis published in The Lancet Psychiatry suggested the equivalent of one joint can induce psychotic and other psychiatric symptoms in healthy adults with no history of a major mental illness.

In “Psychiatric symptoms caused by cannabis constituents: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” the researchers their findings highlighted the acute risks of cannabis use, as “medical, societal, and political interest in cannabinoids continues to grow.” Significantly, they concluded that CBD (the second most common cannabinoid in cannabis) did not induce psychiatric symptoms; and the evidence that it moderated the induction of psychiatric symptoms was inconclusive. These effects were larger with intravenous administration than with inhaled.

Commenting on the results for Medscape, senior investigator Oliver Howes said “As clinicians, we need to be aware that the medical use of marijuana comes with a risk of inducing psychiatric symptoms, even in people with no vulnerability, and this needs to be factored into decisions to prescribe and to monitor.” Even if the symptoms are short-lived, people need to be aware of them because not only van they be distressing, but they can also affect decision-making and behavior. With regard to the failure of the researchers to find evidence that CBD moderates the psychotic effects of THC, Howes said, “I think it’s fair to conclude there’s a lack of consistent evidence that CBD is protecting against THC’s effect.” The mean age of the subjects ranged from early to late 20s.

An editorial of the study by Carsten Hjorthøj and Christine Merrild Posselt said the finding that low doses of THC can induce psychotic symptoms was “extremely worrying,” because they were similar to those found in medical marijuana. They also said there was no clear evidence that concurrent administration of CBD reduces symptoms induced by THC. “The authors failed to find any clear evidence that concurrent administration of cannabidiol (CBD) reduced these symptoms. Indeed, such an ameliorating effect was observed in only one of four included studies.”

This growing scientific consensus is not reflected in the mainstream public discourses, which have a major effect on the political agenda to decriminalise or legalise cannabis. It also appears that, in many places (eg, several US states), the first thing to be legalised is medicinal cannabis followed by increasing decriminalisation and sometimes complete legalisation of cannabis. It is thus of utmost importance that the public and politicians are informed of the most up-to-date evidence on cannabis. Adding to the state of this evidence is the systematic review and meta-analysis by Guy Hindley and colleagues in The Lancet Psychiatry. The authors demonstrate that Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) leads to an increase in total symptoms, which was assessed in nine studies, with ten independent samples, involving 196 participants: standardised mean change in scores (assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the Positive or Negative Syndrome Scale) 1·10 (95% CI 0·92–1·28, p<0·0001). The effect sizes were also large for other symptoms (including general psychiatric symptoms), and were induced even with low doses of THC, somewhat similar to the doses often seen in medicinal cannabis, which we find extremely important and worrying.

The significance of the above research findings should not be lost on Pennsylvania citizens and politicians. As the availability of cannabis increases in the state, as the potency of THC in that marijuana increases, we will see a corresponding increase of psychosis and other mental health-related problems among regular users. This is the future of marijuana legalization in Pennsylvania.

Medical marijuana has been legal in Pennsylvania since April 6, 2016. The first dispensary opened in the Pittsburgh area in Butler PA, on February 1, 2018. But medical marijuana dispensaries continue to spring up like “weeds.” The Weedmaps website indicated there were 39 dispensaries in the Pittsburgh area. Nineteen advertised they provided Curbside pickup.

John Fetterman, the current lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania, is running for the office of U.S. Senator and wants to see Pennsylvania “go full Colorado.” Its governor, Tom Wolf, has publicly supported the legalization of recreational marijuana. There has been legislation proposed by two state senators, the Adult-Use Cannabis Act, to legalize recreational marijuana in the state. See “Should Pennsylvania Go ‘Full Colorado’ With Marijuana?” Part 1 and Part 2.