Repeating Past Mistakes with Esketamine

Ketamine has been touted as effective treatment for depression. A recent study by Anand et al said ketamine was “noninferior” to ECT as therapy for treatment-resistant depression without psychosis. Commenting for Medpage Today, the lead author said it was surprising that ketamine was at least at least effective as ECT, which he said is the gold standard for treatment resistant depression. Commenting on the study, Robert Freedman, MD, said it was noteworthy that all the patients considered for the study were initially referred to ECT because it was thought that ECT was their best option. But he thought the results were not life-changing: “Ketamine treatment was effective, but by 6 months, a brief period in a lifetime of depression, the quality of life was no better with the agent than with ECT.”

A longer duration of treatment increases the likelihood of both drug dependence and cognitive adverse effects, including dissociation, paranoia, and other psychotic symptoms. ECT clinics have informed consent documents that list the various cognitive and other adverse effects of that treatment. A similar informed consent document for ketamine should caution patients and clinicians that temporary relief may come with longer-term costs.

Ketamine is a psychoactive substance that makes the “gold standard” of a double-blind research methodology (neither the participants nor the researchers know which treatment participants are receiving) difficult to implement. In a new study that has not yet been peer-reviewed, Lii et al gave volunteers with mild to moderate depression ketamine while they were preparing to go under general anesthesia, essentially blinding them to the psychedelic or dissociative effects. 38.6% guessed their assignment correctly—no better than chance—indicating the anesthesia had masked the drug’s dissociative effects.

Reviewing the study for Science, Claudia Lopez Lloreda reported both groups experienced a 15-point drop in their depression scores. About 40% of the participants still had more than a 12-point decrease 3 days after the ketamine infusion, “meaning they are in remission for their depression.” That improvement was similar to the antidepressant effects of ketamine in other studies. But the doses of anesthesia used in Lii et al were much lower than that used in the other antidepression studies.

All of this suggests that neither ketamine nor the anesthesia by themselves may do much to alleviate depression, says Theresa Lii, an anesthesiologist at Stanford and co-author of the study. Instead, simply going through the complex, orderly treatment procedure itself—during which participants receive attention and one-on-one interactions with doctors and psychiatrists—benefits people. By merely participating in this trial, she says, participants in both the ketamine and placebo groups may have created an expectation that they were going to get better—and they did.

Peter Simons, who reviewed the study for Mad in America, pointed out that on the secondary outcome measure of the study, by day 3 of the follow up, both the ketamine treatment group and the placebo group had a 40% remission rate. “By the end of a week, the placebo group had 57.9% of patients in remission, compared to just 31.6% of those who received ketamine.” After two weeks, the placebo group was still doing better. The researchers suggested the placebo effect may be responsible for supposed powerful antidepressant effects of ketamine. Quoting from the Conclusion of the >Lii et al study,

Secondary and exploratory outcomes also found no evidence of benefit for ketamine over placebo. These findings differ from those of prior antidepressant trials with ketamine conducted without adequate masking, where the large effect sizes reported may reflect expectancy bias [placebo effect]. Our results suggest that ketamine may actually be ineffective for the short-term treatment of MDD.

Introducing Ketamine’s Chemical Cousin: Esketamine

Mark Horowitz and Joanna Moncrieff asked, “Are we repeating mistakes of the past?” in their article for The British Journal of Psychiatry. They were primarily concerned with esketamine, a chemical cousin of ketamine, but they began with a summary of what is known about ketamine which has been licensed as an anaesthetic for five decades. They noted patients often report several unusual symptoms when recovering from ketamine anaesthesia, including delusions, hallucinations delirium and confusion; sometimes ‘out of body’ experiences. It commonly elevates blood pressure and heart rate, and has been associated with fatal heart failure and myocardial infarction as well as stroke and cerebral hemorrhage.

Used recreationally since the 1970s, ketamine or ‘special K’ produces a dissociative state characterized by a sense of detachment often referred to as the ‘K-hole.’ See “Falling Down the K-Hole.” It’s also addictive, quickly inducing tolerance. “Stopping regular use causes a withdrawal syndrome characterised by anxiety, dysphoria and depression, shaking, sweating and palpitations, and craving the drug.” The way it produces its psychoactive and addictive effects is not entirely clear.

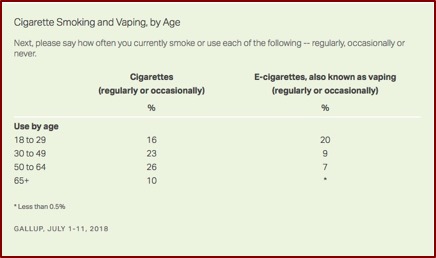

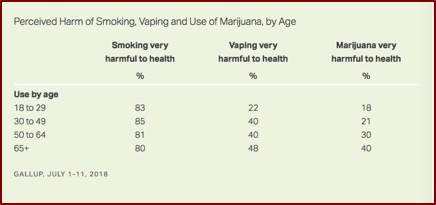

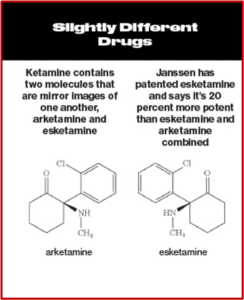

Intravenous ketamine was shown to have “rapid-onset antidepressant effects” in as little as 2 hours. While some researchers have claimed it leads to a genuine, long-lasting antidepressant effect, this has not been established in randomized trials. Since ketamine was already licensed for use, Janssen applied to license one of its enantiomers, (S)-ketamine or esketamine, which is more potent than ketamine. After their application was approved, Janssen received patent exclusivity on the new drug application for several years; and the profit from that approval. See the following graphic, taken from Bloomberg Businessweek comparing ketamine and esketamine.

The FDA normally requires two positive efficacy trials to license a drug, showing a statistically significant difference between esketamine and placebo. But Janssen only had one trial that was statistically significant. The three efficacy trials lasted 4 weeks, shorter than the 6 to 8-week trials the FDA usually requires for drug licensing. Janssen also defined “treatment resistant depression” in a fuzzy way that included many current antidepressant users. Participants with treatment resistant depression could be those who had “failed” with two different antidepressants.

The FDA normally requires two positive efficacy trials to license a drug, showing a statistically significant difference between esketamine and placebo. But Janssen only had one trial that was statistically significant. The three efficacy trials lasted 4 weeks, shorter than the 6 to 8-week trials the FDA usually requires for drug licensing. Janssen also defined “treatment resistant depression” in a fuzzy way that included many current antidepressant users. Participants with treatment resistant depression could be those who had “failed” with two different antidepressants.

The only positive study wasn’t really that positive. It found a difference of 4 points on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) that favored esketamine over an inert placebo. This difference corresponded to less than minimal change (a reduction of 7-9 points on the MADRS); and was one-quarter the size of the placebo response. Participants were also unmasked/unblinded by the noticeable psychoactive effects of esketamine inflating the apparent difference between esketamine and placebo.

The FDA then allowed Janssen to submit the results of a discontinuation trial as evidence of efficacy. The study design was problematical as an efficacy trial because withdrawal effects from esketamine can be mistaken for relapse of depression. Ketamine is recognized as having withdrawal effects and both ketamine and esketamine are Schedule III Controlled Substances. Yet the study report suggested there were no evidence of a withdrawal syndrome on the Physician Withdrawal Checklist. It was not clear how items on the checklist were distinguished from identical items in the MADRS.

As half (48.7%) of relapses occurred in the first 4 weeks following esketamine cessation, the time most likely for withdrawal effects to occur, and as the relapse rate in the placebo group became ‘closer to esketamine with each week’, as highlighted by the FDA, confounding of ‘relapse’ by withdrawal seems likely.

The FDA also noted a concern that the positive results were driven by a single site in Poland. There was a 100% relapse rate in the placebo group, compared with a 33% relapse rate in all the other sites. “It has been demonstrated that if this outlier site is excluded there is no difference between esketamine and placebo (the P-value changes from 0.012 to 0.48), leading to the conclusion that the findings are ‘not robust’.”

There was also disturbing evidence with how the FDA rationalized data on six reported deaths during the licensing trials. There were three suicides occurring after the participant’s last dose of esketamine. The FDA attributed these deaths to “the severity of the patients’ underlying illness.” Yet two of the participants had no indication of suicidal ideation during the study, either at entry or the last visit. Data was not available for the third participant.

Others have argued that these cases might fit with a pattern of a severe withdrawal reaction, consistent with other reports of suicide associated with recreational ketamine, and are significant enough in number to constitute a worrying signal.

An increase in depression and suicidality was also observed during esketamine treatment. Six participants in the esketamine group of the short-term trials became more depressed, compared to only one in the placebo group. Five participants expressed increased suicidal ideation in the esketamine group, compared to two in the placebo group. Paradoxically, Janssen sought and received an expansion of the use of esketamine to include acutely suicidal patients. See “Doublethink With Spravato?”

Horowitz and Moncrieff concluded that history is repeating itself: “A known drug of misuse, associated with significant harm, is increasingly promoted despite scant evidence of efficacy and without adequate long-term safety studies.” But they are not the only individuals concerned with the potential problems with esketamine-related adverse events. Gastalon et al analyzed adverse events (AEs) reported in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting system (FAERS) between March 2019 and March 2020. They found 962 registered reports of esketamine-related AEs in one year, reinforcing worries regarding the safety and acceptability of esketamine. Signals (i.e., statistically significant disproportionality) were detected for disassociation, sedation, feeling drunk, suicidal ideation and completed suicide.

When the trials submitted to the FDA are examined, serious questions with regard to the approval process of esketamine can be raised. The post approval assessment of FAERS data seems to indicate that this sloppy process set up a post marketing examination of the real-world safety and acceptability of esketamine. And it seems Horowitz and Moncrieff legitimately asked if we were repeating with esketamine the past mistakes made with ketamine.

This is the latest of several previous articles I’ve written about my concerns with using ketamine and esketamine to treat depression. In addition to the above-linked articles see “Esketamine Craze,” “In Search of a Disorder for Ketamine,” “Hype and Concern with Esketamine,” “Evaluating the Risks with Esketamine,” “Safety Concerns with Esketamine” and more on my website: Faith Seeking Understanding.