Support and Defend Against Suicide

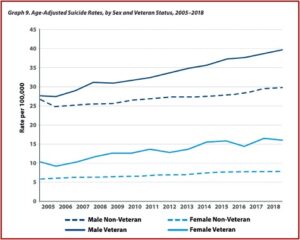

There has been an alarming increase in the number of veterans who commit suicide each year. The latest statistics in the 2020 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report indicated that the number of veteran suicide deaths per year in 2018 was 6,435, an increase 379 per year since 2005. Age- and sex-adjusted suicide rates for the U.S. adult population was 18.3 per 100,000 in 2018. For veterans, their age- and sex-adjusted rates were 27.5 per 100,000 in 2018. “Over the period 2005-2018, age- and sex-adjusted suicide rates rose faster among Veterans than among non-Veteran U.S. adults.”

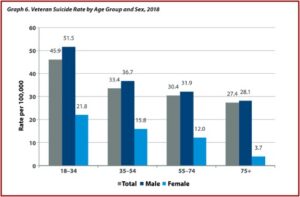

Veterans between the ages of 18 and 34 had the highest suicide rate in 2018, 45.9 per 100,000, while veterans 75 and older had the lowest suicide rate in 2018, 27.4 per 100,000. The absolute number of suicides was highest among veterans 55-74 years old, accounting for 40% of all veteran deaths by suicide in 2018. There were clear sex differences with Veterans, where the age-adjusted suicide rate among women was 15.9 per 100,000 and 39.6 per 100,000 among men. Suicide rates rose faster among men than among women both for veteran and non-veteran populations. See the following graphs from the 2020 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report.

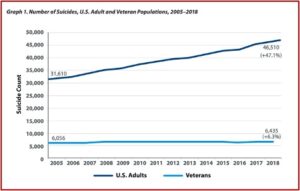

Compared to the steep rise of suicides among U.S. adults, these increases may not seem so alarming. The suicide rate for U.S. adults has increased 47.1% since 2005. The number of American adults who died by suicide in 2018 was 46,510, and 31,610 in 2005. This compares with a 6.3% increase among veterans during the same time period. The number of suicide deaths among veterans in 2018 was 6,435; and in 2005 the number of veteran suicides was 6,056. See the following graph.

Yet an analysis of the data from the 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report by Robert Whitaker suggested a somwhat disturbing factor hiding in the statistics. In “Screening + Drug Treatment = Increase in Veteran Suicides,” Whitaker noted the increase in suicide among Veterans was at least partly driven by the VA’s suicide prevention efforts. The VA’s screening protocols resulted in a greater number of veterans coming into psychiatric care, where treatment with psychiatric drugs is regularly prescribed. “Suicide rates have increased in lockstep with the increased exposure among veterans to such medications.”

Suicide prevention efforts began in the U.S. in the late 1980s, when The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and other organizations like the American Psychiatric Association and the National Alliance on Mental Illness drew attention to suicide as an “unrecognized public health” problem. Individuals with mood disorders who were “untreated” were said to be at particularly high risk of suicide. “The Foundation pushed screening programs as a way to get more people into treatment. Its advisory board and presidents touted antidepressants as ’anti-suicide’ pills.”

The American Psychiatric Association, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, and the pharmaceutical companies that sold antidepressants all helped promote this message to the public. In 1997, their efforts prompted both houses of Congress to declare suicide a “national problem.” Two years later, U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher issued a “Call to Action to Prevent Suicide,” and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services formed a task force, composed of individuals and organizations from the private and public sectors, to develop a “National Strategy for Suicide Prevention.” The task force published its recommendations in 2001, which doubled-down on the “public health” approach that had been promoted by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Government agencies launched suicide prevention efforts. Crisis call centers were created; depression screening programs were introduced. Checklists like the CDC Depression checklist and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) were developed. Medical professionals were trained to recognize the “warning signs” for suicide. “The goal was to get more people struggling with mood disorders into treatment, with antidepressants recommended as a first-line therapy.”

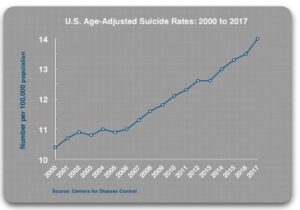

The prescribing rates for antidepressants have steadily increased since 2000. And the age-adjusted suicide rate has also increased from 10.4 per 100,000 in 2000 to 14.0 per 100,000 in 2017. The CDC reported past month use of antidepressants increased from 7.7% in 1999-2002, to 12.7% in 2011-2014. The age-adjusted suicide rate for Americans rose from 10.4 per 100,000 in 2000 to 14.0 per 100,000 in 2017. Whitaker’s data on suicide rates was only age-adjusted, not age- and sex-adjusted suicide rates, so his statistics will not be an exact match with those reported above in the National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Reports. See the following graph from the Whitaker article.

The failure of this approach to suicide prevention, which emphasizes getting people into treatment, is not a uniquely American phenomenon. In the 1990s, the World Health Organization urged countries around the world to develop national mental health policies and to improve their mental health services, which included providing their citizens with better access to psychiatric medications. The belief was that this would lead to better mental health outcomes, which would become visible in the form of reduced suicide rates.

Researchers from the UK, Denmark and Australia have now conducted three studies of whether such efforts have affected suicide rates, and all came to the same conclusion: improved access to psychiatric services and psychiatric drugs was associated with an increase in national suicide rates.

Soon after Prozac came to market in the late 1980s a significant number of patients taking Prozac began having suicidal thought (See “Antidepressant Fall from Grace, Part 1”). There were numerous case reports of people taking the drug who committed suicide. At this point, there is clear evidence that SSRI and SNRI antidepressants can prompt suicidal impulses and acts in some users. In 2003, David Healy and a team of researchers conducted a metanalysis of all random controlled trials (RCTs) of SSRIs and found that suicide attempts were 2.28 times more likely with an SSRI than a placebo.

Like the federal government, the VA sees suicide as a “public health” issue. In 2006 it appointed a National Suicide Prevention Coordinator. The next year it established a toll-free Veterans Crisis line. It has steadily increased resources devoted to this issue, even spending almost $20 million for Make the Connection to market the VHA’s services to veterans. The VA introduced mandatory screening for all veterans. This screening is a regular feature of VHA care, with screening of some sort as part of every patient appointment.

The VA’s clinical guidelines for treating depression and PTSD, the two most commonly diagnosed psychiatric disorders, recommend SSRI and SNRI antidepressants as first-line therapies. A 2015 report by the General Accounting Office (GAO) said 94% of all VHA patients diagnosed with depression from 2009 to 2013 were prescribed an antidepressant. “Studies of VHA patients with PTSD have reported that about 80% are prescribed a psychiatric medication, with antidepressants the drug class of choice.” Polypharmacy, taking multiple medications, is common with 35% of those diagnosed with depression taking two classes of psychiatric drugs and 15% taking three classes of drugs. Those diagnosed with PTSD had an even more pronounced polypharmacy, with 36% taking two classes of psychiatric drugs and 25% taking three or more classes.

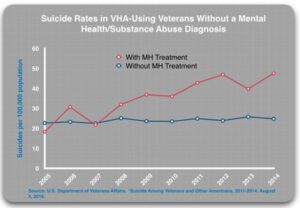

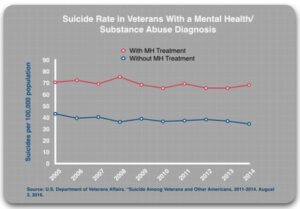

In the 2016 report, Suicide Among Veterans and Other Americans, the VA divided patients into four subgroups: 1) undiagnosed and untreated (for a mental health or substance use disorder); 2) undiagnosed and treated (with either a psychiatric drug or non-pharmacologic treatment); 3) diagnosed and untreated; and 4) diagnosed and treated. Given the regular screening for mental health disorders, undiagnosed patients apparently did not show symptoms of depression, PTSD or any other psychiatric disorder that would have generated a diagnosis during the screening process. These patients should be at low risk of suicide and theoretically, any treatment should further reduce this risk.

The “diagnosed” patients should be at a higher risk of suicide. Suicide prevention efforts focus on getting these patients into treatment, with antidepressants seen as a first-line therapy than can lower the risk of suicide. Thus, if suicide prevention efforts are helpful, the suicide rate for the diagnosed patients who are treated should be lower than for diagnosed patients who, for whatever reason, shun treatment. The 2019 GAO report found that 18% of diagnosed patients did not get treatment.

The results were as follows. Those without a diagnosis who received MH treatment were more likely to die by suicide than those without a diagnosis who did not receive treatment. “In 2014, those who got treatment died at twice the rate of the ‘untreated’ group.”

Those with a mental health or substance use diagnosis who received mental health treatment were also about twice as likely to die by suicide than those who were diagnosed but did not receive mental health treatment. “The difference in suicide rates for the treated and untreated groups is consistent over time, year after year.” The suicide rates for those diagnosed with a mental health or substance use diagnosis have remained stable since 2005. They have hovered around 70 per 100,000 population. “The reason that the suicide rates for VHA patients have been rising is that the VA’s suicide prevention efforts—the outreach campaigns and the mandatory screening—have led to a steady increase in the number of veterans diagnosed and treated for those disorders.”

The data for the four subgroups suggested an increased the risk of suicide with the diagnosed and treated group having the greatest risk:

- Undiagnosed/untreated: 24.8 per 100,000

- Diagnosed/untreated: 34.4 per 100,000

- Undiagnosed/treated: 47.6 per 100,000

- Diagnosed/treated: 68.2 per 100,000

This finding runs directly counter to the variable suicide rates that would be expected if the “treatment” were effective. Yet it is consistent with RCT data showing antidepressants double the risk of suicide compared to placebo. Since the VA launched its suicide prevention efforts in 2006, there have been more than 70,000 suicides. “That is a number greater than the total of all combat deaths since 9/11.”

When you join the military, you take an oath to “support and defend” the Constitution against all enemies, foreign or domestic. Fulfilling that oath means you risk being killed in combat. But it doesn’t mean you have to be willing to risk committing suicide from taking psychiatric medications.