Counterfeit Pills, Snapchat and Overdose Deaths

Image by Hasty Words from Pixabay

WPVI-TV, channel 6 in Philadelphia told a story about a new legal battle over drugs available on social media. More than 60 families are suing Snapchat, arguing the overdose deaths of their children were due to the social media app. They are demanding changes to protect their children, claiming they died after buying illegal drugs sold by dealers on the app. One parent said, “Snapchat is the largest open-air drug market we have in the United States when it comes to our kids.”

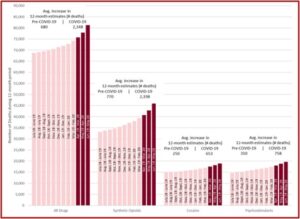

CNN reported the number of drug overdose deaths is still increasing, but seems to be slowing. New estimates from the CDC estimates were 112,024 people died from a drug overdose in the 12-month period ending in May of 2023. This was a 2.5% increase over the 12-month period ending in May of 2022 (109,261). Dr. Katherine Keyes, a professor of epidemiology, said, “There were extraordinary increases in 2020 and 2021 that have started to flatten out in 2022 – now going into 2023. They’re not declining yet. But the pace of the increase is certainly slowing.”

However, certain states have seen steep increases in overdose deaths in comparison to national totals. For example, overdose deaths in Washington increased more than 37%, from 2,373 to 3,254. Fentanyl and other synthetic opioids were involved in most overdose deaths, followed by psychostimulants like methamphetamine. Washington’s dramatic increase in overdose deaths may have been fueled by the availability of counterfeit pills, which we will look at below.

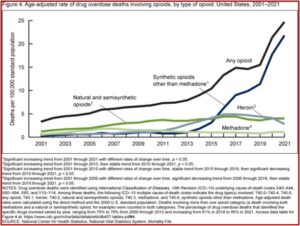

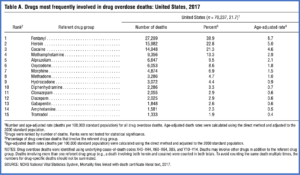

A CDC report said more than 1 million people died between 1999 from and 2021 of a drug overdose. Synthetic opioids other than methadone seem to be the main driver of drug overdose deaths. “Nearly 88% of opioid-involved overdose deaths involved synthetic opioids.” Opioid were involved in 75.4% of all drug overdose deaths.

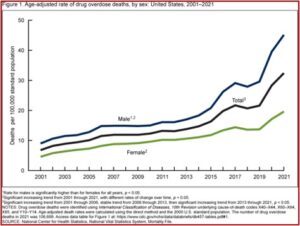

A NCHS data brief released in December of 2022 indicated drug overdose deaths were stable from 2006 through 2013, but then increased from 13.8 per 100,000 in 2013 to 32.4 in 2021. From 2020 to 2021, the rate increased 14% from 28.3 to 32.4 per 100,000. For each year from 2001 through 2021, the rate for males was higher than females. Notice from the following figure the dramatic increase in overdose deaths that begins in 2019, the year before the COVID pandemic.

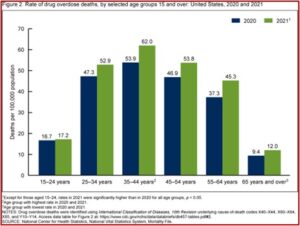

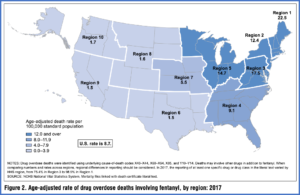

Despite the concerns of parents with Snapchat making it easy for dealers to connect with teenagers seeking drugs, there were four other age groups with higher rates of overdose deaths. Among adults aged 25 and older, the rate of drug overdose deaths was higher in 2021 compared to 2020. The rates were highest for adults aged 35-44 (53.4 and 62.0 per 100,000 respectively) and lowest for people 65 and older. See Figure 2 below.

The drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone (fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol) increased at different rates from 2001 through 2021. Natural and semisynthetic opioid overdose deaths (i.e., oxycodone and hydrocodone) increased from 1.2 to 3.5 per 100,000 in 2010 and then leveled off, reaching 4.0 per 100,000 in 2020 and 2021. The rate of overdose death involving methadone increased from 0.5 in 2001 to 1.8 in 2006. Then it decreased through 2019 to 0.8, and remained stable through 2021 (1.1). “Of the drugs examined, only drug overdose deaths involving heroin had a lower rate in 2021 than in 2020 (2.8 and 4.1, respectively).” See figure 4 below.

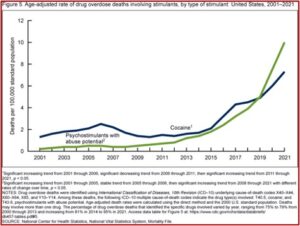

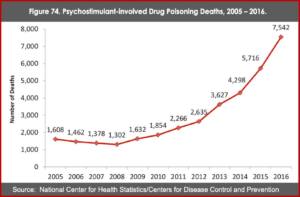

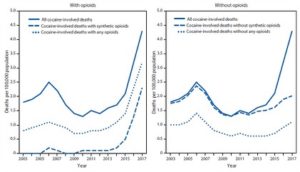

Overdose deaths from cocaine and stimulants were also on the rise. Cocaine-related overdose deaths was a bit of a roller coaster ride, increasing from 1.3 per 100,000 in 2001 to 2.5 in 2006, then decreasing to 1.5 in 2001, and then increasing to 7.1 in 2021. “The rate in 2021 was 22% higher than in 2020 (6.0).” The rate of overdose deaths involving psychostimulants (i.e., amphetamine, methamphetamine and methylphenidate) increased from 0.2 in 2001 to 0.5 in 2005, remaining stable through 2008. Then it increased from 0.4 in 2008 to 10.0 in 2021. The rate in 2021 was 33% higher than the rate in 2020 (7.5). See Figure 5 below.

Drug overdose deaths have risen fivefold over the past 20 years. The rate for males increased from 39.5 to 45.1 and the rate for females increased from 17.1 to 19.6, from 2020 to 2021. For both sexes, the highest rates were for adult between 35 and 44. The rates of drug overdose deaths involving opioids and stimulants increased from 2020 to 2021.

Counterfeit Pills

One disturbing trend that seems to be driving that increase in overdose deaths is the evidence of counterfeit pill use in the U.S. In a September CDC Morbidity and Mortality Report (MMWR), the CDC said these pills are not manufactured by pharmaceutical companies, but are made to look like legitimate drugs, frequently oxycodone and alprazolam (Xanax). Counterfeit pills often contain illicitly manufactured fentanyls and illicit benzodiazepines like bromazolam, etizolam and fluaprazolam. They increase the risk of overdose by exposing individual users to drugs they did not intend to use and did not know they were in the pills they were buying.

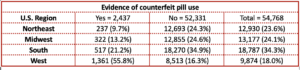

The overall increase of overdose deaths with evidence of counterfeit pill use increased from 2% to 4.7%, driven by an increase from 4.7% to 14.7% in Western states. More than half of overdose deaths with evidence of counterfeit pills (55.8%) occurred in Western states such as Washington. See the following table reproduced from data in Table 1 of the above CDC MMWR report.

The report had these key findings. First, the overall percentage of overdose deaths with evidence of counterfeit pills remained under 6%, but more than doubled from 2.0% in the third quarter of 2019 (July-September) to 4.7% in the fourth quarter of 2021 (October-December). The percentage more than tripled in Western states. Second, the percentage of deaths with evidence of counterfeit pills using illegally manufactured fentanyl (IMF) was more than double the percentage of deaths without evidence of counterfeit pill use.

Evidence of counterfeit pill use more than tripled in western jurisdictions, indicating IMFs, which are frequently present in counterfeit pills, are infiltrating drug markets in western U.S. states. Historically, white-powder IMFs have been less prevalent in western states because of difficulty mixing with predominantly black tar heroin prevalent in that region. The highest percentages of deaths with evidence of counterfeit oxycodone use (both alone and with counterfeit alprazolam) were in western jurisdictions, whereas nearly one half of deaths with evidence of counterfeit alprazolam use only were in southern jurisdictions. This finding suggests that exposure to different types of counterfeit pills and drugs might vary by region. Prevention and education materials that incorporate local drug seizure data and information about regional drug markets might be particularly effective at highlighting relevant counterfeit pill types and reducing deaths.

Those who died from counterfeit pills were significantly younger and more often Hispanic. Counterfeit pills have been marketed towards younger persons, where they may also exhibit more risk-taking behaviors than do older persons. The higher percentage of Hispanic persons could reflect the has implications for access to and use of prevention messaging materials and harm reduction services. “It is important to ensure that prevention messaging and harm reduction outreach are tailored to younger persons and the Hispanic population to address potential engagement, language, or other barriers.”

The DEA reported their lab testing revealed that 4 out of 10 counterfeit pills contain at least 2 mg of fentanyl, a potentially lethal dose. Criminal networks are mass producing counterfeit pills and marketing them as legitimate prescription pills. They’re often sold on social media and e-commerce platforms, which make them widely available to anyone. In 2021, the DEA seized 20 million fake pills, more than the 2 previous years combined. They’ve been identified in all 50 states.

In “Overdosing,” I wrote of the overdose problem as it existed in 2016, before fentanyl, counterfeit pills and Snapchat had become part of the problem. There I referred to “Melanie,” the first person I worked with who eventually became a heroin overdose statistic in the late 1980s. In that article is a map of Pennsylvania showing the drug-related overdose deaths by county in 2014. Philadelphia County even then had the most reported deaths, followed by Allegheny County, where I live. Legislation allowing first responders to carry naloxone to reverse an overdose had just been passed. Let’s continue to fight against the everchanging and adapting drug trade and never forget those who were taken too soon by overdose like Melanie.