Over the last several months news of the COVID-19 pandemic has flooded the U.S. news media. Fears of a resurgence of positive cases and deaths from the virus are the new concern as states relax social distancing guidelines. When you look at the CDC website tracking total cases and deaths due to COVID-19, a clear geographic pattern is evident. California, Illinois, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and Rhode Island all have reported 40,000 or more cases, while Alaska, Hawaii, Montana, Wyoming and Vermont have reported less than 1,000 cases. Unfortunately, worry over COVID-19 has driven concern over drug overdose deaths as a public health concern from the consciousness of most people.

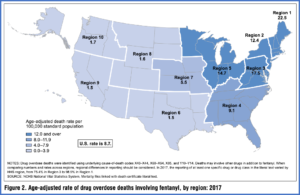

The CDC also reported a pattern to its data on overdose deaths in a “National Vital Statistics Report,” that illustrated the most lethal drug by geographic region. Overall, the drug most frequently involved in overdose deaths in the U.S, was no surprise; it was fentanyl. It accounted for approximately 39% of all drug overdose deaths. When the data is grouped regionally, fentanyl was the drug most frequently involved in overdose deaths east of the Mississippi and methamphetamine was the drug most frequently involved west of the Mississippi. Region 7, consisting of Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri and Kansas broke this pattern in reporting fentanyl as the drug most frequently involved in overdose deaths. See the following map for fentanyl taken from the October 2019 edition of the “National Vital Statistics Reports.”

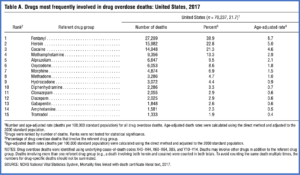

The top 15 drugs belonged to several drug classes: opioids (fentanyl, heroin, hydrocodone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol), benzodiazepines (alprazolam, clonazepam, and diazepam), stimulants (amphetamine, cocaine, and methamphetamine), an antihistamine (diphenhydramine) and an anticonvulsant (gabapentin). Nationally, 38.9% of drug overdose deaths involved fentanyl (including fentanyl metabolites, precursors, and analogs), 22.8% involved heroin, 21.3% involved cocaine, and 13.3% involved methamphetamine. Alprazolam, oxycodone, and morphine were each involved in 6.9%–9.5% of the drug overdose deaths in 2017, while methadone, hydrocodone, diphenhydramine, clonazepam, diazepam, gabapentin, amphetamine, and tramadol were each involved in less than 5.0%.

The top 15 drugs belonged to several drug classes: opioids (fentanyl, heroin, hydrocodone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol), benzodiazepines (alprazolam, clonazepam, and diazepam), stimulants (amphetamine, cocaine, and methamphetamine), an antihistamine (diphenhydramine) and an anticonvulsant (gabapentin). Nationally, 38.9% of drug overdose deaths involved fentanyl (including fentanyl metabolites, precursors, and analogs), 22.8% involved heroin, 21.3% involved cocaine, and 13.3% involved methamphetamine. Alprazolam, oxycodone, and morphine were each involved in 6.9%–9.5% of the drug overdose deaths in 2017, while methadone, hydrocodone, diphenhydramine, clonazepam, diazepam, gabapentin, amphetamine, and tramadol were each involved in less than 5.0%.

Among the opioids, fentanyl, heroin, hydrocodone (Vicodin) and oxycodone (OxyContin) have been getting the lion’s share of the overdose press. But notice that methadone, used as an opioid maintenance drug, and tramadol also made the list. Benzodiazepines like alprazolam (Xanax), clonazepam (Klonopin) and diazepam (Valium) have been a growing, and hidden misuse and overdose problem, overshadowed by opioids like heroin and fentanyl. Gabapentin (Neurontin) likely became an overdose drug because of its use as a cheap way to potentiate an opioid high.Six drugs were found among the top ten most frequently involved drugs in all 10 of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS( public health regions: alprazolam, cocaine, fentanyl, heroin, methadone and oxycodone. See the following table listing the top fifteen drugs most frequently involved in overdose deaths.

Commenting on the CDC data in the “National Vital Statistics Report” for ABC News, Holly Hedegaard, an epidemiologist and co-author of the report, noted how the drug problem was not the same across the country. “What’s interesting is that the patterns are different across the U.S.”

Zachery Dezman, an assistant professor of emergency medicine, thought the regional variations were the end product of cultural influences. Methamphetamine use beginning in California could account for the drug’s strong regional presence. “Like all culture, it varies from region to region and is a result of history, demand, law enforcement.” Although methamphetamine can be made cheaply, using material found on most farms, it produces a large amount of toxic waste. “So methamphetamines are more often produced in rural or isolated areas where it is easier to hide from the authorities.”

Dezman’s assessment may have been true in the 1990s, but there seem to be other factors influencing the geographic divide noted above. Writing for The Fix, Seth Ferranti indicated that 90% of the methamphetamine in the U.S. comes from Mexico, primarily manufactured in super labs by drug cartels. The Mexican labs, like the TV show Breaking Bad, are making a very pure, relatively cheap meth. Local suppliers then “cut” the meth with cheaply produced fentanyl in order to sell more of it at a lower expense. Brandon Costerison, a project manager for the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse said: “It’s a lot stronger, so we’re seeing a lot more psychosis, but we’re also seeing it being tainted with fentanyl, which is leading to more deaths.”

According to the 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment, the methamphetamine sampled in the second half of 2017 averaged 96.9% pure. The price per gram of meth was $70. The purity had increased 6%, while the price decreased 13.6%. Most of the Mexican transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) or drug cartels are involved in trafficking methamphetamine, which has led to increased competition between the cartels. The authors of the 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment speculated this competition led the Mexican TCOs to try moving into new territories and experiment with novel smuggling methods, such as the use of drones, in attempts to increase their methamphetamine customer base.

Though not favored by traffickers due to their noise, short battery life, and limited payload, advances in technology may make this method more feasible. As the technology advances and addresses these shortcomings, drones may prove more attractive to smugglers, which in turn may increase their prevalence as a smuggling technique across the border.

Currently methamphetamine laboratory seizures in the U.S. are at the lowest level in 15 years and domestic production is at its lowest point since 2000. From a high of 23,703 in 2004, there were 3,036 seizures in 2017. Between 2012 and 2017, the number of seized domestic meth laboratories decreased by almost 78%. This can be attributed, at least partly, to the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act (CMEA), which was signed into law on March 9, 2006 to regulate over-the-counter sales of methamphetamine precursors like ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. But it left a supply hole the Mexican cartels were happy to fill.

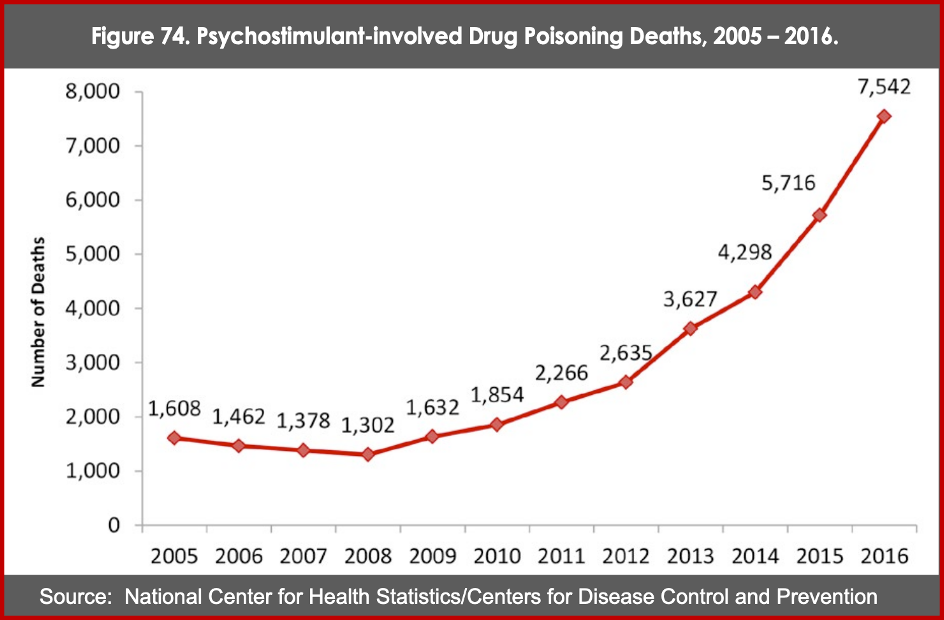

The number of deaths due to psychostimulants continues to increase dramatically. According to the CDC, methamphetamine drug poisoning deaths are included under the broader category of psychostimulants, which include MDMA, amphetamine and caffeine. While the value changes yearly, recently 85 to 90% of the drug poisoning deaths reported under psychostimulants mentioned methamphetamine on the death certificate. “According to the CDC, in 2016 there were 7,542 psychostimulant drug poisoning deaths in the United States, representing a 32 percent increase from 2015, and a 387 percent increase since 2005.” See the following figure from the 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment.

Despite the growth of methamphetamine use, for people who use the drug, treatment options are slim. Currently there is no FDA-approved medication for methamphetamine use disorder, but there seems to be some promising results with naltrexone. Available as a pill or an extended release injection (Vivitrol), naltrexone is used to prevent a relapse with opioid use and it suppresses the euphoria and pleasurable sensations from drinking alcohol. There have been some studies of naltrexone as a treatment for methamphetamine use disorder.

Ray et al published a double blind, placebo-controlled study of naltrexone with individuals meeting DSM criteria for methamphetamine abuse or dependence. The results indicated that naltrexone reduced the pleasurable effects of the drug as well as cravings. The lead author of the study, Lara Ray told ScienceDaily: “The results were about as good as you could hope for.” She has done several studies on the effectiveness of naltrexone for methamphetamine addiction, including one on how executive function moderated naltrexone effects on methamphetamine-induced craving.

Naltrexone significantly reduced the subjects’ craving for methamphetamine, and made them less aroused by methamphetamine: Subjects’ heart rates and pulse readings both were significantly higher when they were given the placebo than when they took Naltrexone. In addition, participants taking Naltrexone had lower heart rates and pulses when they were presented with their drug paraphernalia than those who were given placebos.

NPR published an article noting how a woman successfully used naltrexone to help her stop using methamphetamine. She had used drugs like cocaine for years, since she was a teenager. But when she tried crystal meth, she said she was hooked from the first hit. “It was an explosion of the senses. It was the biggest high I’d ever experienced.” She went from 240 pounds to 110. She also lost custody of her children. She said three to four hours after she took the first naltrexone pill, she felt better. After taking the second pill, her withdrawal symptoms lessened.

Nancy Beste, the certified addiction counselor and physician’s assistant who treated the woman, has tried naltrexone with about 16 patients who use methamphetamine. It appeared to help reduce cravings in about half of them. She also treats individuals with opioid addiction and all her patients do counseling in conjunction with medication-assisted treatment. Her treatment goal is to eventually wean them off the medications. Unlike buprenorphine and methadone, naltrexone is not a controlled substance with its own addiction potential. In my opinion, that makes it a promising medication assisted treatment (MAT) for methamphetamine.

Drug overdose deaths did not just disappear when COVID-19 arose. The CDC reported 128 people die every day from an opioid overdose. Although the number of drug overdose deaths decreased by 4% from 2017 to 2018, it was still four times higher than in 1999. Prescription-involved deaths had increased by 13.5% while heroin-involved deaths decreased by 4%. Synthetic opioid-involved deaths, excluding methadone, increased by 10%. Methamphetamine-involved deaths accounted for approximately 11% of the of the number of drug overdose deaths in 2018. The COVID-19 pandemic may have overshadowed the opioid epidemic, but it didn’t stop it.

I’ve written about all these drug classes and the potential they have for abuse. For starters, see “Through the Fentanyl Looking Glass,” “Doubling the Risk of Overdose,” and others on opioids. Also see “Global Trouble with Tramadol”, “Gabapentinoids Perpetuate Addiction” and “The Evolution of Neurontin Abuse” for more on the problems with gabapentin or tramadol. See “Are Benzos Worth It?” “It Takes Away Your Soul” and “Dancing with the Devil” on concerns with benzodiazepines. Search on the website for the drug you are interested in reading more about in other articles.