Ticking Time Bomb of Speedballing

What do the following celebrities have in common: John Belushi, Chris Farley, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, and River Phoenix? Their deaths were attributed to speedball use, a combination of cocaine and heroin or morphine. Speedballs may also combine other pharmaceutical opioids, benzodiazepines or barbiturates along with stimulants, as it seems was the case with the death of Phillip Seymour Hoffman. The combination of stimulant and depressant drugs suppresses the usual negative side effects of each class of drugs, which can lead to misjudging the tolerance or intake of one or both drugs. “Due to the countering effect of the cocaine, a fatally high opioid dose can be unwittingly administered without immediate incapacitation, thus providing a false sense of tolerance until it is too late.”

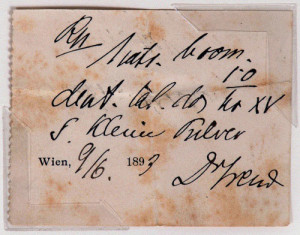

Combining stimulants and opiates dates back at least to Sigmund Freud, who unsuccessfully attempted to counteract a friend’s morphine addiction with cocaine. Freud later acknowledged he may have hastened his friend’s death by “trying to cast out the devil with Beelzebub.” Nevertheless, Freud continued his personal use of cocaine despite his failed attempt to counter his friend’s morphine addiction. Several scholars have debated whether or not Freud’s use of cocaine influenced his developing theories, especially their emphasis on sex. For more information on Freud and his cocaine use, see “Sigmund Freud was a Cocaine Evangelist and Addict.”

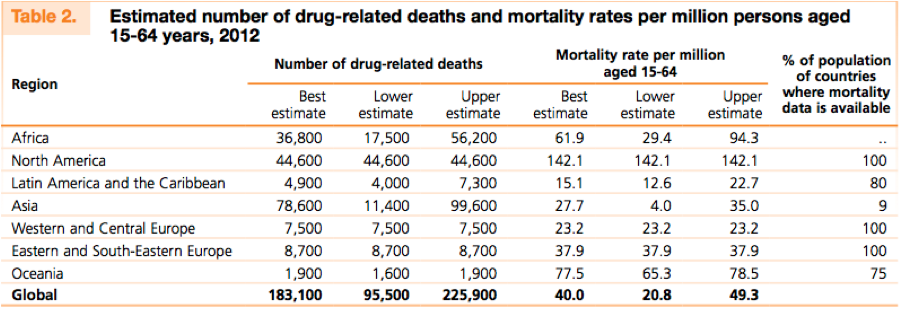

The polysubstance misuse of stimulants and opioids has not received much media attention, but in the evolving nature of the opioid crisis that may be changing. The CDC recently published the results of an investigation of drug overdose deaths with cocaine and psychostimulants in the US between 2003 and 2017. In 2017 there were 70,237 drug overdose deaths, of which nearly a third (32.9%) involved cocaine, psychostimulants or both. Nearly three quarters of cocaine-involved deaths and about one half of the psychostimulant-involved deaths involved at least one opioid. Between 2006 and 2012 there was a decrease in overall cocaine-involved death rates that seems to have paralleled a decline in cocaine supply, but they began to increase again in 2012 (See the following figures).

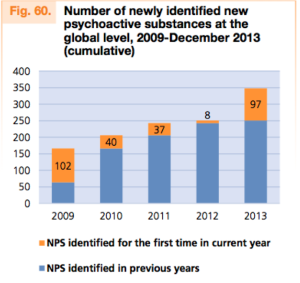

Drug overdoses continue to evolve along with emerging threats, changes in the drug supply, mixing of substances with or without the user’s knowledge, and polysubstance use. In addition, the availability of psychostimulants, particularly methamphetamine, appears to be increasing across most regions. In 2017, among drug products obtained by law enforcement that were submitted for laboratory testing, methamphetamine and cocaine were the most and third most frequently identified drugs, respectively. Previous studies also found that heroin and synthetic opioids (e.g., illicitly-manufactured fentanyl) have contributed to increases in stimulant-involved deaths. Current findings further support that increases in stimulant-involved deaths are part of a growing polysubstance landscape. Although synthetic opioids appear to be driving much of the increase in cocaine-involved deaths, increases in psychostimulant-involved deaths have occurred largely without opioid co-involvement; however, recent data suggest increasing synthetic opioid involvement in these deaths.

Among the 70,237 overdose deaths in 2017, 13,942 (19.8%) involved cocaine and 10,333(14.7%) involved psychostimulants. Death rates increased from 2016 to 2017 in both drug categories across demographic categories such as sex and race. Male overdoses involving cocaine increased 31.9%. Male overdoses involving psychostimulants increased 32.4%. Female overdoses involving cocaine increased 38.9%. Female overdoses involving psychostimulants increased 35.7%.

White, non-Hispanic overdoses involving cocaine increased 35.3%. White, non-Hispanic overdoses involving psychostimulants increased 40.0%. Black, non-Hispanic overdoses involving cocaine increased 36.1%. Black, non-Hispanic overdoses involving psychostimulants increased 33.3%. Hispanic overdoses involving cocaine increased 25.0%. Hispanic overdoses involving psychostimulants increased 33.3%.

Preliminary data for 2018 suggests continuing increases in drug overdose deaths. Given the rise in deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants “and the continuing evolution of the drug landscape,” the authors called for a rapid, multifaceted and broad approach that included both surveillance efforts and prevention and response strategies. The mixture of opioids in stimulant-involved overdoses underscored the importance of continued opioid overdose surveillance and prevention measures, including the expansion of naloxone availability. The CDC is expanding its drug overdose surveillance to include stimulants. And it is implementing evidence-based opioid prevention efforts such as improving the ability for users to access care and collaborations with public health and public safety organizations.

The increase of stimulant deaths without opioid involvement requires efforts to identify and improve access to care for persons who only use stimulants as well. The authors also suggested implementing upstream prevention efforts focusing on shared risk with both opioids and cocaine. The Fix cited comments by Hans Brieter, a psychiatry professor at Northwestern University, on how cocaine is thought of as a safer drug to use by many people today. “There’s been a lot of bad press about other drugs.” Younger people today didn’t see firsthand the 1970s dangers of cocaine, he said, so they mistakenly believe it to be the safer drug. Increased efforts towards protective factors that address substance use/misuse and improve risk reduction (“don’t use alone”) should be made as well.

The concluding sentence of the CDC Report called for collaboration between the community and public health and safety organizations, in order to understand the local drug scene and reduce its risks to users of both drugs. “Continued collaborations among public health, public safety, and community partners are critical to understanding the local illicit drug supply and reducing risk as well as linking persons to medication-assisted treatment [MAT] and risk-reduction services.” Here we may be seeing a peek under the hood at what the authors fear the most with their suggested linking to MAT, namely the increasing synthetic opioid involvement in cocaine-involved or psychostimulant overdose deaths. Remember that speedballing mixes a stimulant with a depressant. Due to the offsetting effects of the two drugs, a fatal amount of an opioid could be used without a realization of the danger until it’s too late.