“Unpunishable” is Unpalatable, Part 1

Unpunishable, by Danny Silk, was biblically unpalatable to me. He sought to present Unpunishable as a biblical way to lead people in repentance, reconciliation and restoration. He opened with an example of a pastor who had committed adultery for the second time and was ultimately restored to his position of leadership within Bethel Church in Redding California. I would agree from Silk’s description of the first time the man committed adultery, that neither he nor the senior pastors of his first church seemed to handle the aftermath of his adultery in a way to lead him in repentance; and that his experience of it discouraged him from true reconciliation. But I don’t think this example of restoration was enough to accept the conclusion that what was wrong was the senior pastors were operating from a belief system called the punishment paradigm.

The core belief of the punishment paradigm was said to be shame-based: “My flaws and failure make me unworthy of love, belonging, and connection.” We believe we deserve disconnection and punishment, as does everyone else who has flaws and failures. This leads to individuals being motivated by the fear of punishment/disconnection, where their strategy becomes avoiding punishment by hiding or fitting in (false fruit); or by rebelling and refusing to comply with the “punishment.” The goal of the punishment paradigm was said to be self-preservation.

Silk said what was true about punishment was that it positioned you as opponents rather than partners in the discipline process. People were not empowered to clean up their mess. It produced shame and disconnection. Punishment distracted people from learning about the real consequences of their choices. “Instead, they only learn the fear of punishment.” As a consequence of his experiences with punishment, he was led to the belief that anyone who chose “the path of repentance, reconciliation, and restoration do not need to be punished.” This path would set them free from “the toxic punishment paradigm” and empower them to pursue a new belief system, identity, narrative, motivation, strategy and goal.

I don’t think that the consequence of “punishment” inescapably leads to opposition rather than partnership in the discipline process. The failure to repent of sin does. A person who was truly repentant of their sin would comply with what Silk described as punishment or discipline. It also seems that Silk’s view of punishment has the potential, in some instances, to shift responsibility from an unrepentant individual to the punishment paradigm. The “toxic punishment paradigm” is then responsible for the individual’s failure to repent, not the hardness of their heart.

As Silk moved into chapter three, he said: “The Bible shows us that the punishment paradigm isn’t some socially constructed, cultural phenomenon. It is a universal human experience with deep spiritual roots. In fact, this paradigm came to be at the very beginning, when humankind fell from God through sin.” Stop and notice what was said here. Silk is recasting the story of the Fall and original sin as the beginning of the punishment paradigm. This is the first of several examples of faulty theology and exegesis by Silk that distorts Scripture to fit his punishment paradigm.

The first error in his interpretation of Genesis 2 and 3 was when he conflated the meaning of “naked” ʿ(ārôm,) in Genesis 2:25 with “crafty” (ʿā∙rûm) in the next verse, 3:1. The Hebrew term for naked has a symbolic sense of exposure and vulnerability and is a different word than ʿā∙rûm, crafty. Frequently in Scripture ārôm has a symbolic sense of exposure and vulnerability, as when Isaiah walked “naked” to signify Egyptian prisoners being led away by the Assyrians (Isaiah 20:2-4) or when Saul lay naked and prophesied after the Spirit of God came upon him (1 Samuel 19:24). Nakedness is also associated with shame in Hebrew thought, as with the discovery of a drunken Noah by Ham (Genesis 9:22-23), but Genesis 2:25 clearly negates such an interpretation. Genesis 2:25 is making the point that Adam and Eve may have been naked (vulnerable), but they were not ashamed of it.

A similar term, êrōm, is used ten times in the OT to designate spiritual and physical nakedness. In Genesis 3, it refers to Adam and Eve after their sin (Genesis 3:7, 10, 11). More than just an awareness of their physical nakedness, Adam and Eve are also aware of their guilt before God—they had lost their innocence. “Their relationship with God was impaired, upsetting their relationship to each other.” In Ezekiel 16:7, 22, 29; 23:29 and Deuteronomy 12:29, ʿêrōm is used of the personified Jerusalem, suggesting both her material and spiritual poverty. Used in Ezekiel 18:7, 16 it indicates the proper social concern of righteousness in providing clothes for needy.

So, there is a subtle wordplay going on here in Genesis with the probable intent of reinforcing the meaning of what is being described. In Genesis 2:25 Adam and Eve were naked (ʿārôm) and not ashamed. The following verse, Genesis 3:1, reads: “Now the serpent was more crafty (ʿā∙rûm) than any other beast of the field that the LORD God had made.” Genesis 2:25 contrasts the naked innocence and vulnerability of Adam and Eve to the craftiness of the serpent in Genesis 3:1. As a result of the serpent’s craftiness, Adam and Eve sinned. Ironically, their first bit of newfound wisdom was to realize that they were naked (ʿêrōm) before God (3:7, 10, 11). The primary consequence to the Fall was the realization their relationship with God was impaired and their shame was for this consequence of their sin, not that they were physically naked. See “Nakedness in Genesis.”

Silk did get to a similar understanding of the consequences of the Fall, but then he inserted his sense of what happens with the punishment paradigm. He rightly said Adam and Eve’s sin led to their disconnection from God, one another and creation. But then he said this trauma led to the fear of disconnection: “This psychological and spiritual trauma left them feeling unprotected, powerless, and threatened, which in turn produced shame—the fear of disconnection.” The fear of punishment/disconnection is the “Motive” in Silk’s description of the Punishment Paradigm described above and illustrated in the chart on page 38 of Unpunishable.

Failing to see the intensification described by the wordplay of Adam and Eve naked (ʿārôm) and not ashamed, the serpent’s craftiness (ʿā∙rûm), which led to Adam and Eve’s sin and their realization they were naked (ʿêrōm) physically and spiritually before God led to another interpretive mistake. As Silk discussed how Adam and Eve responded to God after their sin, he said rightly that Adam and Eve’s fear of God was because of sin. But he wrongly said they fell into spiritual darkness (and couldn’t find their way back to God) as soon as their eyes were opened. They fell into spiritual darkness when they ate the fruit. As a consequence of their sin, they didn’t know how to repent and were not able reconcile or restore their relationship with God. It was to this reality that their eyes were opened.

Silk said Adam and Eve became locked in a false view of the universe and its Creator, “and it was this view that produced the fear of punishment in their hearts.” Trapped in this distorted reality, repentance and reconciliation—resubmitting to God’s authority and repairing the connection—seemed scary, impossible. According to Silk:

This was the catch-22 into which the enemy had drawn them—to step out from the covering of God’s authority, attempt to make their own rules, see this backfire spectacularly, and then find that their hearts were bound through shame and fear, to the addiction of continuing to try to make the rules apart from God, even though doing so would only produce more disconnection, shame and fear.

Silk said Adam and Eve reacted to this fear by hiding. “Instead of running to God to cover and protect them—and ultimately restore their shattered trust and connection—they made covering for themselves. They both agreed that self-protection was the way to go.”

This understanding of the consequences of the Fall fits with Silk’s punishment paradigm, but is not consistent with how the Fall has been viewed by the church since the time of Augustine. Silk appears to wrongly assume that before Christ, Adam and Eve could have, in principle, repented and reconciled with God, but their bondage “prevented them from finding their way back to God.” Without Christ, how could they find their way back to God? It is important to get a clear sense of the Fall and its impact on humanity. I think Silk’s imposition of his punishment paradigm on the text distorts it.

In his book The Enchiridion, Augustine described the four states of a Christian life. The first state is when he or she is sunk in the dark depths of ignorance, living according to the flesh, and undisturbed by conscience or reason. This was the human condition after the Fall: where we were not able not to sin (non posse non peccare). The second state comes when knowledge of sin comes through the law. Since the Spirit of God has not yet begun its aid, humanity was thwarted in its efforts to live according to the law. And being overcome by sin, became its slave (2 Peter 2:19). The effect produced by the knowledge of the law is that now they have the additional guilt of willful transgression of God’s law.

The third state comes when the Spirit of God begins to work within a person at salvation. Although there is still the old nature of flesh that fights against them (for their disease is not completely cured), they live “the life of the just by faith” in righteousness. That is, as long as they do not yield to their lusts and desires, and conquer them by the love of holiness. The one who by steadfast piety advances in this course shall attain the peace that shall be perfected after this life is over—the repose of the spirit. And they will achieve the resurrection of the body. This is the fourth state. “Of these four different stages the first is before the law, the second is under the law, the third is under grace, and the fourth is in full and perfect peace.”

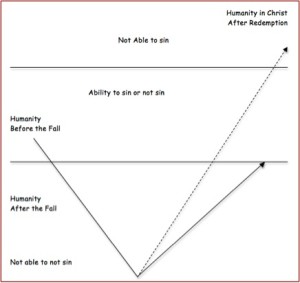

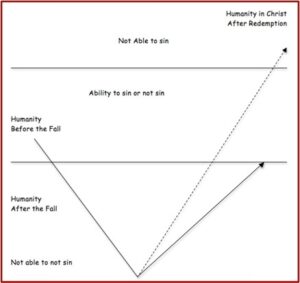

According to Augustine, this grace was not absent previously, but was veiled and hidden in harmony with the arrangements of the time. “For none, even of the just men of old, could find salvation apart from the faith of Christ; nor unless He had been known to them could their ministry have been used to convey prophecies concerning him to us, some more plain, and some more obscure.” With the help of a graphic representation adapted from a lecture by Richard Gaffin, we can illustrate Augustine’s fourfold state of humanity as follows:

Humanity before the Fall had the ability to sin or not sin. They were created in the image of God as self-conscious, free, responsible religious agents even with regard to sin. They were able to sin or not sin. This was before the Fall and before Augustine’s description of the four states.

Humanity before the Fall had the ability to sin or not sin. They were created in the image of God as self-conscious, free, responsible religious agents even with regard to sin. They were able to sin or not sin. This was before the Fall and before Augustine’s description of the four states.

After of the Fall, humanity could not help but sin. Original sin was now part of our nature and we were not able not to sin, the first state. With the knowledge of sin through the law, things got worse and we discovered just how sinful we could be. This is represented by the solid descending line. We experienced the truth of Romans 7:19, “For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing.” This was the second state, where humanity had knowledge of the law of God, as well as their inability to achieve it under the law.

But Romans 7 does not end with a realization of hopelessness and powerlessness. Who will save us from this body of death? “Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ out Lord! So then, I myself serve the law of God with my mind, but with my flesh I serve the law of sin.”

As a result of the grace of Christ, we receive the gift of His Spirit and can begin to resist the pull of our old nature and strive to walk in righteousness, not yielding to the lusts and desires of the flesh. This is represented by the ascending dotted line and represents the third state. Progress up the line is progressive sanctification. Without the redemptive work of Christ, humans can in principle “be all they can be,” but they cannot transcend their fallen nature. This is represented by the solid ascending line.

The fourth state is reached after our redemption by Christ. The person who is steadfast in their piety advances up the dotted line, becoming more Christ-like. In the end we stand with the other sheep on Judgment Day and hear the Son of Man say: “Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world” (Matthew 25:34).

It is in this fourth state, when we are in full and perfect peace with Christ, that we will be truly unpunishable, as we will be unable to sin, non posse peccare.

Look soon for other sections of this article, “Unpunishable is Unpalatable” here: Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.