In The Canon of the New Testament, Bruce Metzger commented how the history of the New Testament canon was a long, continuous process, rather than a series of sporadic events. Although church leaders and even Roman emperors organized councils and synods, during the early centuries of the Church, “the collection of New Testament books took place gradually over many years by the pressure of various kinds of circumstances and influences.” While this was one of the most vital developments in the early days of the Church, it took place almost as if it were an afterthought—with little comment on how, when, and by whom it was birthed. “Nothing is more amazing in the annals of the Christian church than the absence of detailed accounts of so significant a process.” Here is a short summary of how it happened.

The process of canonicity for the New Testament began in the early part of the second century and continued up to the fourth century, when ecumenical creeds, like the Creed of Nicea began to be formulated. Athanasius, who had attended the counsel of Nicea as a young priest, listed the 27 books of the NT canon for the first time in 367 in his “Thirty-Ninth Festal Epistle” as the bishop of Alexandria. Within this letter he said:

. . . Again [after a list of the Old Testament books] it is not tedious to speak of the [books] of the New Testament. These are, the four Gospels, according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. After these, the Acts of the Apostles and Epistles called Catholic, of the seven apostles: of James, one; of Peter, two; of John, three; after these, one of Jude. In addition, there are fourteen Epistles of Paul the apostle, written in this order: the first, to the Romans; then two to the Corinthians; after these, to the Galatians; next, to the Ephesians; then to the Philippians; then to the Colossians; after these, two of the Thessalonians; and that to the Hebrews; and again two to Timothy; one to Titus; and lastly, that to Philemon. And besides, the Revelation of John.

By 100 AD, all 27 books of the NT were in circulation; and the majority of the writings were in existence twenty to forty years before this. All but Hebrews, 2 Peter, James, 2 John, 3 John, Jude and Revelation were universally accepted, according to NT Scholar F. F. Bruce. He dates the four Gospels as follows: Mark (64 or 65 AD), Luke (before 70 AD, but after Paul’s two year detention in Rome around 60-62 AD), Matthew (shortly after 70 AD). John (90-100 AD). Dating the book of Acts should follow the dating for Luke, between 60/62 and 70 AD. The ten Pauline epistles were written before the end of his first Roman imprisonment as follows: Galatians (48); 1 and 2 Thessalonians (50); 1 and 2 Corinthians (54-56); Romans (57); Philippians, Colossians, Philemon, and Ephesians (around 60). The Pastoral Epistles contain signs of a later date than the other Pauline Epistles (63-65), perhaps during a second imprisonment around 65 AD, leading to his death.

New Testament scholar Donald Gutherie suggested the following dates for the remaining books left undated by Bruce: Hebrews (60-90 AD); 2 Peter (62-64); James (50); 2 John (90-100); 3 John (90-100); Jude (65-80); and Revelation (90-95).

The manuscript evidence for the New Testament documents is embarrassingly abundant. There are over 5,000 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament (in whole or in part) in existence. The best and most important ones date from around 350 AD: the Codex Vaticanus and the Codex Sinaiticus. Two other important early MSS are the Codex Alexandrinus (5th century AD) and the Codex Bezae (5th/6th century AD).

In contrast, for Caesar’s Gallic War, there are 9 or 10 good MSS; the oldest from 900 years after Caesar. The History of Thucydides (written 460-400 BC) and the History of Herodotus (written 488-428 BC) are known from about eight MSS, the earliest from 900 AD. “Yet no classical scholar would listen to an argument that Herodotus or Thucydides is in doubt because the earliest MSS of their works which are of any use to us are from over 1,300 years later than the originals.” The bottom line: the manuscripts for the New Testament documents are reliable. But how did they come together as canon?

There were several developments, influences and individuals who exerted pressure on the early Church to establish more precisely “which books were authoritative in matters of faith and practice” among the many that claimed to have that authority. The earliest list of New Testament books was drawn up by Marcion around 140 AD. See “Heresy, Canon and the Early Church, Part 2” for more on Marcion and the influence of his and other heresies on the developing NT canon.

Marcion only accepted the authority of the nine Pauline epistles to the churches and Philemon. He also removed and liberally edited any passages where Paul commented favorably on the Law or quoted the Old Testament. He only trusted one of the Gospels—Luke—yet again edited it heavily, removing most of the first four chapters. This was because he rejected the virgin birth of Jesus, as he believed that as a divine being, Jesus could not have been born of a woman.

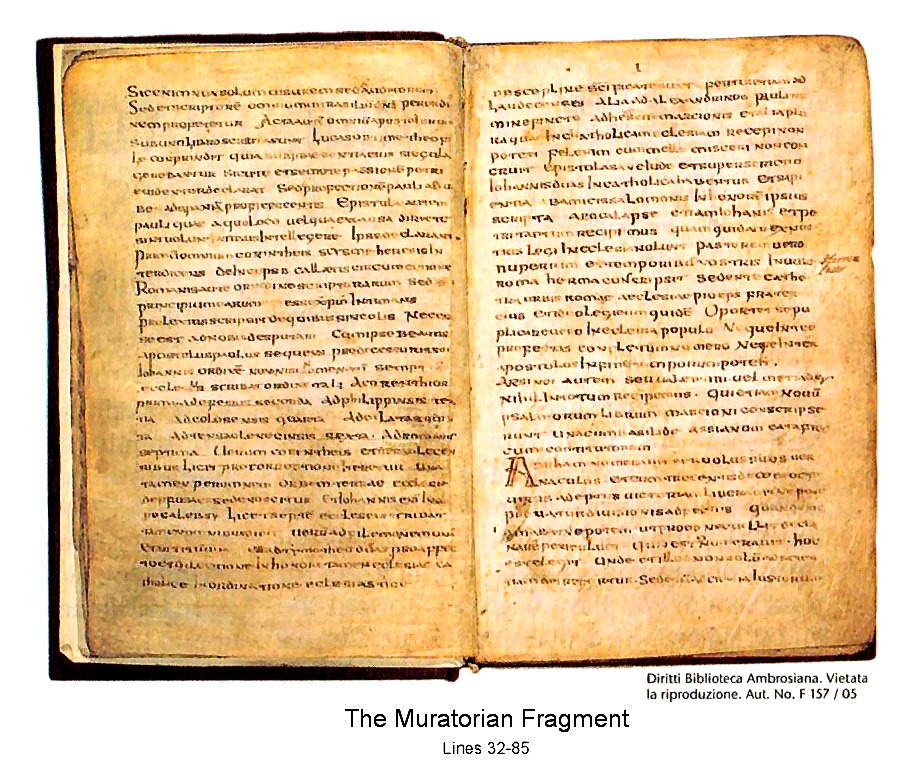

One of the most important documents for the early history of the NT canon is the Muratorian Canon, named after its discoverer, the Italian historian and theological scholar, Ludovico Antonio Muratori. It composition is dated to the latter part of the second century. It is not a canon in the narrow sense of the term; it’s not a bare list of titles. Instead of just cataloguing the books accepted by the Church as authoritative, the Muratorian Canon gives a kind of introduction and commentary for each book.

It listed and discussed the four Gospels, the Book of Acts, thirteen Epistles of Paul: Corinthians (1 and 2), Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, Galatians, Thessalonians (1 and 2), and Romans. Paul also wrote four Epistles to individuals from ‘personal affection,’ but they were later held to be sacred in the esteem of the Church “for the regulation of ecclesiastical discipline.” They were: Philemon, Titus and Timothy (1 and 2).

Next it mentions Jude and two Epistles of John. Speculation is that since the author had already mentioned the First Epistle of John in conjunction with the fourth Gospel, he only mentioned the two smaller ones here. Two apocalypses are mentioned, that of John and that of Peter—“though some of us are not willing that the latter should be read in church.” Books not mentioned include 1 and 2 Peter, James and the Epistle to the Hebrews.

Eusebius, the bishop of Caesarea around 314 AD, wrote and revised his work, Ecclesiastical History, several times during the first quarter of the fourth century. He placed the NT books into three categories: 1) those whose authority and authenticity were universally acknowledged; 2) those which all the witnesses were equally agreed in rejecting; and 3) those which were disputed books, yet familiar to most people in the church. In the first category were: the four Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, the Pauline Epistles (in which he included Hebrews), 1 Peter and 1 John, and the Apocalypse of John. In the third category were: the Epistles of James, Jude, 2 Peter, and 2 and 3 John.

He added that he also felt compelled to list works that were cited by heretics “under the name of the apostles,” including: the gospels of Peter, Thomas, and Matthias, the Acts of Andrew and John. “The character of the style is at variance with apostolic usage, and both the thoughts and the purpose of the things that are related in them are so completely out of accord with true orthodoxy that they clearly show themselves to be the fictions of heretics.” These were to be cast aside as “absurd and impious.”

There seemed to be three essential criteria that had to be met for a document to be included in the NT canon: orthodoxy, apostolicity and consensus among the churches.

Orthodoxy was assessed by the “rule of faith” or the canon or rule of truth. Was a given document congruent with the basic Christian tradition recognized as normative by the Church? NT era writings with any claim to be authoritative were judged by the nature of their content. “A book that presents teachings deemed to be out of harmony with such tradition would exclude itself from consideration as authoritative Scripture.”

Apostolicity could mean having a close relationship with an apostle, like Mark with Peter and Luke with Paul—as well as direct apostleship—with John and Paul. With the writer of the Muratorian Canon there is a clear sense of the importance he placed on the qualifications of the NT authors as eyewitnesses or as careful historians.

The third test of authority was its continuous acceptance and usage by the Church. If a book had been accepted by many churches, over a long period of time, it was in a stronger position to be accepted as canon. Hebrews is a good example of this principle. Jerome wrote that it did not matter who the author of the book of Hebrews was, because it was the work of a church-writer and was constantly read in the churches. Augustine said the Christian reader: “will hold fast therefore to this measure in the canonical Scriptures, that he will prefer those that are received by all the Catholic Churches to those which some of them do not receive.”

By the time of Augustine (354-430) the NT canon, as it is given today in the Protestant Bible, was widely accepted. It was Augustine who declared the debate over the canon of Scripture was over. At a series of provincial synods, he voiced the following with regard to the closing of the canon: “Besides the canonical Scriptures, nothing shall be read in church under the name of the divine Scriptures.” In closing, we’ll look at his advice to the Christian reader of the sacred writings. In On Christian Learning, just before he listed the 27 books of the NT canon, he said:

The most skillful interpreter of the sacred writings, then, will be he who in the first place has read them all and retained them in his knowledge, if not yet with full understanding, still with such knowledge as reading gives,—those of them, at least, that are called canonical. For he will read the others with greater safety when built up in the belief of the truth, so that they will not take first possession of a weak mind, nor, cheating it with dangerous falsehoods and delusions, fill it with prejudices adverse to a sound understanding. Now, in regard to the canonical Scriptures, he must follow the judgment of the greater number of catholic churches; and among these, of course, a high place must be given to such as have been thought worthy to be the seat of an apostle and to receive epistles. Accordingly, among the canonical Scriptures he will judge according to the following standard: to prefer those that are received by all the catholic churches to those which some do not receive. Among those, again, which are not received by all, he will prefer such as have the sanction of the greater number and those of greater authority, to such as are held by the smaller number and those of less authority. If, however, he shall find that some books are held by the greater number of churches, and others by the churches of greater authority (though this is not a very likely thing to happen), I think that in such a case the authority on the two sides is to be looked upon as equal.

Information on the birth of the New Testament canon discussed here was taken primarily from The Canon of the New Testament by Bruce Metzger and The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? By F. F. Bruce. For more on the early creeds and heresies of the Christian church, see the link: “Early Creeds.”