“Unpunishable” is Unpalatable, Part 4

In chapter 6 of Unpunishable, “Discipline in the New Testament,” Danny Silk opened with an anecdote of a situation where his sixteen-year-old son stayed out all night. Silk’s assessment of story was that it illustrated discipline, not punishment. He said although the two words are often used interchangeably, “biblically they are completely different experiences that produce very different results.” He then referenced another anecdote from chapter 1 with a pastoral staff member of his home church of Bethel who had committed adultery … twice. The man assessed what happened to him as a contrast between punishment and discipline: “When the first affair happened, I was punished . . . The second time, I was disciplined.” Silk then quoted a passage in Hebrews, saying it was a famous passage on discipline, showing us “what, how and why we learn,” and yet again his interpretation of the passage was biblically unpalatable.

Silk began by saying the word discipline comes from the same word as disciple, meaning learner. He seems to be drawing on the English meaning of the word. Merriam-Webster said discipline comes from discipulus, the Latin word for pupil, which also was the source for the word disciple. However, dicipline can mean punish or chastise as well as teach or train. In fact, the earliest known use of discipline appears to be punishment-related. It was first used in the 13th century to refer to chastisement of a religious nature, such as self-flagellation.

The English sense of discipline does not have a stark difference from the word punishment, at least as Silk uses the two terms in his discussion of the punishment paradigm. But he claimed there were biblical differences that produce very different results. So, let’s look at Hebrews 12:1-11, which he referred to as the famous passage on discipline. He quoted from the Passion Translation, a paraphrase favored by Bill Johnson, a senior leader of Bethel Church.

Note first that he edited out the beginning of verse 1 and completely left verses 2 and 9-10 out of his quote. The initial part of verse 1 (TPT) edited out was: “As for us, we have all these great witnesses who encircle us like clouds.” As Silk is using the passage to support his sense of discipline, it seems he edited out the reference to the “great cloud of witnesses” in chapter 11 in order to center the passage on the point he wanted to illustrate.

Verse 2 in the Passion Translation translated a phrase as “conquered its humiliation” that in the ESV is given as “despising the shame.” This may be the reason for editing out verse 2, as the footnote in the Passion Translation said the Greek meaning is “thinking of its shame.” The Louw-Nida lexicon said the Greek word used here means “a painful feeling due to the consciousness of having done or experienced something disgraceful—‘shame, disgrace.’ Silk connected shame with Adam and Eve realizing they were naked as the consequence of their sin of eating the fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The core belief of his punishment paradigm is shame-based.

In the section of Unpunishable where he quoted Hebrews 12, “Punishment vs. Discipline,” Silk is contrasting the two, punishment and discipline. Quoting a verse that even obliquely alluded to shame would confuse the point he was trying to make, so it seems he did not include it. See Part 1 for more discussion on shame and its relationship to the core belief of the punishment paradigm.

Excluding verses 9-10 seems to have a similar intent, as the verses compare the discipline of God and human fathers. In verse 9, the comparison is an a fortiori argument, from the lesser to the greater: if we respected our earthly fathers who disciplined us, how much more should we respect God our Heavenly Father. In verse 10, the comparison is between temporal and eternal discipline: our earthly discipline has value in this world, but God’s discipline is eternal, for a life that never ends. The verses suggest a greater and lesser discipline, or a temporal and eternal one. The nuance does not fit with the stark contrast Silk wants to portray between punishment and discipline.

After giving his edited quote of Hebrews 12:1-11, Silk said: “The first thing to notice here is that in the new covenant, discipline is a relational exchange between the Father and His children.” Although we do experience discipline by human authority figures, that discipline only functions correctly when those figures accurately represent the heart of the Father. Silk wants to position his sense of discipline in the new covenant as fundamentally between us and the Father. The second thing to see is that the Father’s goal in this exchange is “to heal us of our wounds, train us to overcome sin, and transform our character.”

In other words, in the new covenant, discipline is focused on benefitting the person who has made the mess. In the punishment paradigm, the focus in on protecting the interests of everyone but the offender. . . . This is His process for helping His kids unlearn the punishment paradigm and rebuild their lives in His punishment-free relational paradigm of love, trust, and freedom. Where else can He best show us that His heart is not to punish us, but to remove our shame, forgive us, free us from the fear of punishment, and lead us into loving, safe connection with Him than in our messes and mistakes?

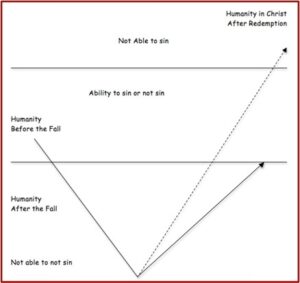

Silk wants to represent his punishment paradigm as the antithesis of Godly discipline. Discipline is what happens in progressive sanctification, as the Father seeks to heal and transform us. Punishment occurs when we are disconnected from the Father, and as a result, strive to avoid punishment, making self-preservation our priority. On page 108, he presented the following as a basic breakdown of the stark differences between punishment and discipline.

| Punishment | Discipline |

| Upholding the rules | Restoring the relationship |

| Pain is inflicted/imposed | Pain is embraced |

| Worldly sorrow | Godly sorrow |

| Repentance is irrelevant | Repentance is essential |

| Forgiveness is irrelevant | Forgiveness is essential |

| Requires submission of control | Requires responsibility, self-control |

| Stopping bad behavior | Transforming heart |

| Good behavior is compliance and manipulative | Good behavior is fruit of love |

| Powerless | Powerful |

| Fear-driven | Love-driven |

| Goal of self-preservation | Goal of connection |

| External law | Internal law |

In summary, it is clear Silk sees an antithetical contrast between punishment and discipline as he describes the punishment paradigm. He said that biblically, they were different experiences, producing very different results. His comment that the word discipline comes from the same word as disciple had some nuance that casts doubt on how he conceived the contrast between punishment and discipline. The Latin word discipulus was the source for disciple. Yet it could also mean punish or chastise. In the 13th century it was used to refer to religious chastisement, such as self-flagellation.

If as Silk said, there is a clear biblical difference between the two terms punishment and discipline, we should see this difference reflected in what he called “the famous passage on discipline,” Hebrews 12:1-11. The Passion Translation is problematic here with some key verses, 12:5b-6: “My child, don’t underestimate the value of the discipline and training of the Lord God, or get depressed when he has to correct you. 6 For the Lord’s training of your life is the evidence of his faithful love. And when he draws you to himself, it proves you are his delightful child.” The Passion Translation said in a footnote that the phrase “draws you to himself” means scourges or chastises in the Greek, but then seems to improperly derive its meaning from the Aramaic word nagad, which can mean “scourge” or “draw.”

There is absolutely no justification for incorporating an Aramaic word into the text here. All other translations Silk uses in Unpunishable, the NIV, the NKJV, and the NASB translate the word in Hebrews 12:6 as chastens or scourges. The Greek word used here in Hebrews 12:6 is mastigoi, which means to chastise or punish with discipline in mind. Used in John 19:1, it has the sense of flog or scourge: “And Pilate took Jesus and flogged him.” The Theological Word Book of the New Testament said mastigoi was used in Hebrews 12:6 to mean to impart corrective punishment. “As the education of a beloved child may sometimes demand blows, so God may sometimes smite His children.”

The Greek word translated as discipline in the Passion Translation, the ESV and the NIV, is paideia, which is derived from pias, meaning “child.” It is not derived from mathetes, meaning disciple, as Silk suggested. David Allen, in his commentary on Hebrews said paideia’s meaning can range between training and corporal punishment: “Generally speaking, it refers to education in Greek tradition and to discipline by punishment in Hebrew tradition. Allen added the following comments:

Sometimes, however, God employs chastising hardships to punish sin in our lives. Along with discipline, God employs fatherly correction. This is not to be thought of as the damning wrath of God, but rather as the corrective punishment of a parent. Verse 6 tells us of these heavenly spankings: “[He] chastises every son whom he receives.” The key word is mastigoi, which means scourging or whipping as an intense form of punishment. If we think God would never do that, we are obviously mistaken. While we are not judicially punished by God as Judge—Christ having borne all the penalty of our sin on the cross—God as Father gives painful, corrective punishment the way any loving parent does, because he wants us to grow up the right way. Many Christians have gratefully testified that the only way God got through to them in their sin and stubbornness was to allow a painful ordeal—the loss of a job, a severe illness, persecution for their faith. Eventually they recognized this as a sign of fatherly care, the kind that only beloved children receive from God.

Allen is not alone in this opinion. In his commentary on Hebrews, Paul Ellingworth also said the meaning of paideia ranges between training and corporal punishment: “Broadly speaking, the Greek tradition emphasized paideia as education, whereas the Hebrew tradition stressed the positive value of (especially God’s) discipline of his people by punishment.” Ellingworth further said:

In Hebrews, as in Proverbs, paideia is explicitly seen as including unpleasant elements; indeed, the theme is introduced because the readers are experiencing the pain of persecution; yet the physical aspect of parental discipline conveyed by mastigoi is not mentioned in the exposition.

An antithetical contrast between discipline and punishment does not exist in Hebrews 12:1-11, nor does it seem to be supported by the meanings attributed to paideia or mastigoi. Instead of biblically being “completely different experiences that produce very different results,” they appear to be biblically complementary.

Silk’s belief system regarding the punishment paradigm cannot be said to have a biblical warrant to support it. As he attempted to demonstrate the biblical reality of his concepts, he disregarded the clear biblical theological significance of Romans 1, claiming the full arc of the biblical story was to set us free from the punishment paradigm. He read the core belief of the punishment paradigm into the text, ignoring how it called for our need for a Savior because of original sin and rebellion in the Fall. Blinded by his belief system, he imputed it into his interpretation of the Genesis story of Adam and Eve, and the Fall. As a result, he ignored or missed the hope that was inserted in the story by God Himself, the protoevangelium of Genesis 3:15. I believe Silk failed in his attempt to present Unpunishable as a biblical way to lead people in repentance, reconciliation and restoration.

Read other sections of this article, “Unpunishable is Unpalatable” here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.