Unintended Consequences of COVID-19

On December 17, 2020, while the country’s attention was focused on the just-approved COVID vaccines, the CDC released a health advisory that noted substantial increases in drug overdose deaths across the U.S. Then, the report estimated that there were 81,230 drug overdose deaths in the 12-months ending in May 2020. This represented a worsening of the drug overdose epidemic in the U.S. and was the largest number of drug overdoses ever recorded for a 12-month time period. The CDC report said it appeared that drug overdose deaths accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. But then a new CDC report released in July of 2021 reported the number of overdose deaths had increased to 92,183 in December of 2020.

The July 2021 CDC report contains interactive figures showing the month-ending counts of overdose deaths by drug class and by states. From December of 2019 until December of 2020 California overdose deaths increased 45.9%; New York State, 37.3%; New York City, 36.6%. The states with the highest increases of overdose deaths were: Vermont, 57.6%; West Virginia, 55.6%; Kentucky, 53.7%; and South Carolina, 52.8%. The overall increase for the U.S. was 29.6%. See the July 2021 CDC report for more information.

A public health researcher for Brown University said to AP News this was a “staggering loss of human life.” While the nation was already struggling with a serious overdose epidemic, “COVID has greatly exacerbated the crisis.” Lockdowns and other restrictions during the pandemic made treatment harder to get. The increased deaths are most likely from people who were already struggling with addiction. Suspensions of evictions and extended unemployment benefits meant there was more money than usual to spend on drugs.

According to Shannon Monnat, a sociology professor at Syracuse University, what is really driving the surge in overdoses is an increasingly poisoned drug supply. “Nearly all of this increase is fentanyl contamination in some way. Heroin is contaminated. Cocaine is contaminated. Methamphetamine is contaminated.”

Reuters reported that during the pandemic, many drug programs were not able to operate. Restrictions meant therapy sessions were done by Zoom, which are not as impactful as in person face-to-face contact. Indirectly, pandemic lockdowns likely contributed to the increase in overdose deaths. The lockdowns intensified feelings of isolation, which is a factor in anxiety and depression, which leads to drug abuse. A health policy expert at John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health estimated on a day-to-day basis, the U.S. is now seeing more overdose deaths than COVID-19 deaths.

In “Drug overdose deaths accelerating due to the pandemic,” the director of the CDC said the disruption of daily life from COVID-19 hit those with substance use disorder hard. “As we continue the fight to end this pandemic, it’s important to not lose sight of different groups being affected in other ways. We need to take care of people suffering from unintended consequences.” Again, we see the problems from fentanyl contamination. Opioids, primarily illegally manufactured fentanyl, were largely responsible for most of the overdose deaths. Synthetic opioid fatalities rose 38.4% from 2019 to 2020.

Recently, the American Medical Association noted a similar spike in overdose deaths driven by opioid deaths. The past president of the American Medical Association, Patrice Harris, warned of the necessity to continue to pay attention to health issues other than COVID. She said:

It is imperative that we continue to talk about other health issues that are impacting our nation . . . We are appropriately focused on COVID, it is still top of mind for most people, and it’s understandable that we can lose focus on other issues … but we still have to make sure we are focused on the overdose epidemic that we continue to experience in this country.

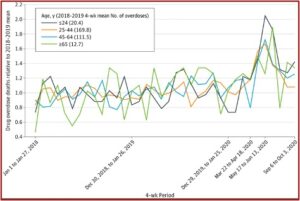

There was a study in in JAMA Network Open, “Trends in Drug Overdose Mortality in Ohio,” that looked at the overdose deaths in Ohio during the first seven months of the pandemic. Fatal overdoses rose sharply from the declaration of the pandemic on March 11th 2020 to the week of May 31st 2020, an increase of 70.6%. The initial spike in deaths was most pronounced for the youngest adults, those up to and including the age of 24. However, fatal overdoses followed a similar pattern in all age groups, including those 65 years and older. See the follow chart from the JAMA article.

Another study published in the Journal of Drug Issues assessed the relationships between COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and opioid overdoses in Pennsylvania. The authors said in an article for the Fix that Pennsylvania was one of the hardest hit states by the opioid epidemic. They found statistically significant increases in overdoses with heroin, fentanyl, fentanyl analogs or other synthetic opioids, pharmaceutical opioids and carfentanil. The researchers suggested in the Journal of Drug Issues that the observed increases were likely to be underestimates because of undercounts of monthly overdose incidents. They recommended these drug clsses be continuously monitored for changing patterns of use to help guide the most effective treatment interventions.

This analysis suggests that the onset of COVID-19 in the state of Pennsylvania, and resulting policy responses to mitigate infection, created unintended consequences for opioid overdose. These unforeseen outcomes obligate attention to how economic effects of the pandemic, coupled with mental health stress and other triggers for addiction, complicate and undermine patterns of opioid use and misuse, and emphasize the need for opioid use to be addressed alongside efforts to mitigate and manage COVID-19 infection.

It was pointed out how the economic recession associated with the pandemic undermined housing policy and access, “which will have lingering effects for social cohesion, access to medical care, and consistent routines critical for addiction management.” Percentages of fatal versus nonfatal overdoses remained relatively constant throughout the study at 16-17%. Heroin accounted for the largest percent (65%) of the total reported opioid-related overdose cases, followed by fentanyl (14%) and the unknown drug class (14%). “Increased mental health stress, social isolation, and economic uncertainty will likely continue to affect those most vulnerable to addiction and relapse.”

The double impact of COVID-19 and drug overdoses induced a drop in life expectancy for 2020. The CDC reported that life expectancy at birth for 2020 was 77.3 years, a decrease of 1.5 years from 78.8 in 2019. This was the lowest it has been since 2003. The decline in life expectancy was primarily due to COVID-19 (73.8% of the negative effect), unintentional injuries (11.2%), and homicide (3.1%). “Increases in unintentional injury deaths in 2020 were largely driven by drug overdose deaths.”

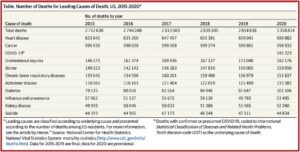

“The Leading Causes of Death in the US for 2020,” published in JAMA, found that COVID-19 was the third leading cause-of-death after heart disease and cancer. There were substantial increases from 2019 to 2020 for several leading causes. Heart disease deaths increased by 4.8%; unintentional injury by 11.1%; Alzheimer disease by 9.8%; and diabetes by 15.4%. Early estimates of life expectancy at birth for January 2020 to June 2020 showed declines not seen since World War II. See the following table taken from “The Leading Causes of Death in the US for 2020.”

The influence of the pandemic on the opioid epidemic has not gone unnoticed by the White House. In March of 2021, President Biden released a Statement of Drug Policy Priorities that said illicitly manufactured fentanyl and synthetic opioids other than methadone (SOOTM) have been the main influence behind the increase. However, overdose deaths from cocaine and other psychostimulants like methamphetamine have also risen. “New data suggest that COVID-19 has exacerbated the epidemic.” The American Rescue Plan, signed into law in March of 2021, set the following drug policy priorities for the administration:

The influence of the pandemic on the opioid epidemic has not gone unnoticed by the White House. In March of 2021, President Biden released a Statement of Drug Policy Priorities that said illicitly manufactured fentanyl and synthetic opioids other than methadone (SOOTM) have been the main influence behind the increase. However, overdose deaths from cocaine and other psychostimulants like methamphetamine have also risen. “New data suggest that COVID-19 has exacerbated the epidemic.” The American Rescue Plan, signed into law in March of 2021, set the following drug policy priorities for the administration:

- Expanding access to evidence-based treatment;

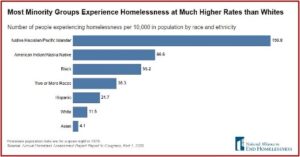

- Advancing racial equity issues in our approach to drug policy;

- Enhancing evidence-based harm reduction efforts;

- Supporting evidence-based prevention efforts to reduce youth substance use;

- Reducing the supply of illicit substances; Advancing recovery-ready workplaces and expanding the addiction workforce; and

- Expanding access to recovery support services.

Concern over the entwined consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and the opioid epidemic exist beyond the US. In an opinion article for the BMJ, Ian Hamilton noted how the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified inequalities such as poverty, unemployment, poor housing and homelessness in the UK. He said these inequalities have been felt most acutely felt by those from the lowest socioeconomic groups. “Until effective ways of reducing social inequality are implemented, the best that we can hope for is timely specialist support for those developing drug related problems, such as dependency.” He concluded that problem drug use is an issue that will be with us for years and we need to build a workforce to meet the demand and ensure that these avoidable fatalities “are just that—avoided.”