Homelessness and COVID-19

The findings for the 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress were published in January of 2021 and it contained some disturbing information. In a single night in 2020, approximately 580,000 people experienced homelessness in the U.S. Sixty-one percent stayed in sheltered locations, while 39% were “living rough” on the street, in abandoned buildings, or wherever they could pitch a tent. For the fourth year in a row, homelessness increased nationwide. The number of people who were homeless increased by 2% between 2019 and 2020. Almost 60% experienced homelessness in an urban area and 53% of all unsheltered people were counted in the nation’s 50 largest cities.

The 2020 AHAR count reflects a 7% increase of individuals staying outdoors with the number of sheltered individuals remained largely unchanged, with a 0.6% decline. “Increases in the unsheltered population occurred across all geographic categories.” The key factor was a sizeable increase (21%) in the number of unsheltered people with chronic patterns of homelessness. This means being homeless for more four times in the past 3 years, or continuously homeless for at least one year.

Unsheltered families with children also increased for the first time since data collection began. In 2020, just under 172,000 people in families with children were homeless. While most of these homeless families (90%) were in sheltered locations, there was an increase of unsheltered families by 13%.

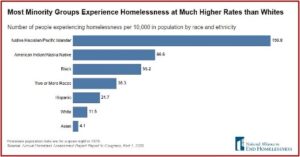

People identifying as black or African American accounted for 39 percent of all people experiencing homelessness and 53 percent of people experiencing homelessness as members of families with children but are 12 percent of the total U.S. population. Together, American Indian, Alaska Native, Pacific Islander and Native Hawaiian populations account for one percent of the U.S. population, but five percent of the homeless population and seven percent of the unsheltered population. In contrast, 48 percent of all people experiencing homelessness were white compared with 74 percent of the U.S. population. People identifying as Hispanic or Latino (who can be of any race) are about 23 percent of the homeless population but only 16 percent of the population overall. [See the following graphic]

Psychological Services published a special issue on homelessness in 2017, “Homelessness as a Public Mental Health and Social Problem.” The authors said after deinstitutionalization in the 1960s, thousands of patients moved out of mental institutions into community-based care became homeless. Under the Bush administration, the federal government began requiring communities to conduct and report annual point-in-time counts of homeless individuals to track the scope of the problem. An epidemiological study found that 4.2% of Americans have experienced homelessness for over one month sometime in their lives and 1.5% experienced homelessness in the past year. “From both epidemiological studies and PIT counts, it is clear that homelessness remains a major problem in the country.”

Psychological Services published a special issue on homelessness in 2017, “Homelessness as a Public Mental Health and Social Problem.” The authors said after deinstitutionalization in the 1960s, thousands of patients moved out of mental institutions into community-based care became homeless. Under the Bush administration, the federal government began requiring communities to conduct and report annual point-in-time counts of homeless individuals to track the scope of the problem. An epidemiological study found that 4.2% of Americans have experienced homelessness for over one month sometime in their lives and 1.5% experienced homelessness in the past year. “From both epidemiological studies and PIT counts, it is clear that homelessness remains a major problem in the country.”

Risk factors that are strongly associated with homelessness include adverse childhood experiences, mental illness and substance abuse. Most research on homelessness has focused on homeless, single, middle-aged men. “But there is increasing study on the growing number of homeless women and families who may have different needs.”

While there have been efforts to provide housing for the homeless or those at risk of homelessness, such as the HUD Exchange, many people who enter supported housing return to homelessness. Comprehensive primary care and behavioral health services have been intentionally integrated into many homeless organizations. Unfortunately, there continues to be limited access to mental health and substance use services available for many in supportive housing.

Nan Roman, the President and CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, said the 2020 report gave a deeply troubling picture of homelessness in the U.S. on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. She said these results show an under-resourced system supposed to meet the needs of people at risk of and experiencing homelessness. While the Alliance was encouraged by the investments federal leaders have made in homelessness and housing resources during the pandemic, “the numbers make it clear that these investments are tragically overdue.”

COVID-19 and Homelessness

The pandemic was a major disruption for homeless system operations. The yearly Point-in-Time (PIT) survey for 2021 of persons who are homeless received new guidance that allowed for flexibility when counting people who were unsheltered. There were allowances made for observation-only counts, samplings, abbreviated surveys, and longer times permitted for the process. There was even a report published to guide those conducting a street-based PIT count that maintained the health and safety of those performing the count as well as those individuals who were homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic. See the National Alliance to End Homelessness for a webinar on “Conducting the 2021 PIT in the Age of COVID-19” and other resources.

In “COVID-19 and the State of Homelessness,” the National Alliance to End Homelessness reported how the pandemic significantly complicated efforts to end homelessness. One expert predicted there would be an increase of 250,000 new people homeless over the course of the year. Consider that before the pandemic, systems were not able to serve everyone experiencing homelessness. “Providers only had capacity to offer an emergency shelter bed to 1 in 2 individuals experiencing homelessness in 2019.” Limited resources resulted in overcrowded shelters and social distancing was difficult, if not impossible. “Unsheltered people lack consistent access to water, soap, and hand sanitizers that help prevent the spread of the virus.”

In “People experiencing homelessness: Their potential exposure to COVID-19,” Lima et al noted how many homeless people already have a diminished health condition, higher rates of chronic illnesses or compromised immune systems, “all of which are risk factors for developing a more serious manifestation of the coronavirus infection.” Those suffering from mental illness potentially struggle recognizing and responding to threats of infection. They also have less access to health care providers who could order diagnostic testing, and if confirmed, isolate them from others in coordination with local. Health departments.

In “Data for: People experiencing homelessness: Their potential exposure to COVID-19,” Neto et al said homeless organizations warned the coronavirus could cause catastrophic harm to unhoused communities. People who sleep in shelters or on the streets already have a lower life expectancy, as well as struggles with addiction and underlying health conditions that put them at greater risk should they develop the virus. Experts say the chronically ill homeless have a unique vulnerability to the coronavirus. “If exposed, people experiencing homelessness might be more susceptible to illness or death due to the prevalence of underlying physical and mental medical conditions and a lack of reliable and affordable health care.”

People experiencing homelessness are increasingly older and sicker. Many have underlying health conditions but lack access to primary-care physicians or preventive health screenings. They struggle to find public bathrooms to maintain their basic hygiene. Those who live in tent encampments or crowded shelters might be unable to keep their distance from others or self-isolate if they show symptoms.

A CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) for May 1, 2020 assessed the infection prevalence of COVID in five homeless shelters for residents and staff members in four U.S. cities—Boston, San Francisco, Seattle and Atlanta. They found that when COVID clusters (two or more cases in the preceding two weeks) occurred, “high proportions of residents and staff members had positive test results for SARS-CoV-2.” Community incidence (the average number of reported cases in the count per 100,000 persons per day during the testing period) varied, with Boston having the highest incidence and San Francisco the lowest.

To protect homeless shelter residents and staff members, CDC recommends that homeless service providers implement recommended infection control practices, apply social distancing measures including ensuring residents’ heads are at least 6 feet (2 meters) apart while sleeping, and promote use of cloth face coverings among all residents. These measures become especially important once ongoing COVID-19 transmission is identified within communities where shelters are located. Given the high proportion of positive tests in the shelters with identified clusters and evidence for presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2, testing of all residents and staff members regardless of symptoms at shelters where clusters have been detected should be considered. If testing is easily accessible, regular testing in shelters before identifying clusters should also be considered. Testing all persons can facilitate isolation of those who are infected to minimize ongoing transmission in these settings.

In the Journal of Internal Medicine, “Addressing the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Persons Experiencing Homelessness,” Barocas et al noted that at least 1 in 5 of 13.8 million adults in rental housing say they are behind in rent. Coupled with an end to the federal eviction moratorium, this could mean an increase of more than 2.7 million newly homeless or unstably housed people in the U.S. Medical conditions such as heart and lung disease disproportionately effect the unsheltered and place them at risk for high morbidity and mortality from COVID-19. “A sudden increase in the number of people without housing or infections in the existing homeless population combined with COVID-19’s current strain on our health care system will greatly reduce our ability to care for this vulnerable population.”

Barocas et al recommended four changes. First, immediate improvements to and expansion of the national shelter system are needed. They believe the situation will become more dire if the federal eviction moratorium is not extended. Federal and state relief plans need to allocate funds for more shelters that are properly staffed and resourced.

Second, there needs to be an improvement with ongoing surveillance to prevent outbreaks among homeless individuals. One of the suggestions was to increase the use of waste water-based epidemiology, the practice measuring biomarkers in wastewater. “Active surveillance of municipal wastewater mapped to homeless shelters could be used to identify insipient outbreaks.” This seems to be a potentially low-cost COVID-19 surveillance method that could be used in low-resource settings such as shelters.

The third recommendation is to develop a universal approach to testing and contact tracing. A lack of testing supplies has led to a disproportionate allocation of tests across society, with more socially disadvantaged individuals encountering challenges when accessing tests. New methods of contact tracing rely on the assumption of stable housing, secure internet, or cell phones with application abilities. While most homeless people own or have access to a mobile phone, they often do not have smartphones that support app-based programs. “We need a dedicated investment in contact tracing in this population; otherwise, expanded testing will be for naught.”

The fourth and final recommendation is to provide places for persons with inadequate housing and without a permanent home to isolate once they are diagnosed with COVID-19 and do not meet criteria for skilled nursing care. Shelters are usually not equipped to convert entire floors into quarantine units. Innovative approaches to help this vulnerable population attain a space to recuperate and limit the spread of COVID-19, such as using hotels or college dormitories for temporary housing, were suggested.

As a nation, we have, thus far, done little to protect persons experiencing homelessness from COVID-19 disease. In the short term, we need funding for the expansion and improvement of our shelter systems, development and implementation of innovative strategies for active surveillance of outbreaks, rapid deployment of more COVID-19 tests coupled with a comprehensive contact tracing strategy, and expanded space for recuperation for this population. For a long-term effect, we need to extend the eviction moratoria and to use the pandemic as an opportunity to expand affordable and low-income housing and establish pathways to regain housing. Continued neglect of this vulnerable population will most certainly lead to considerable strain on the already stretched healthcare system during times of SARS-CoV-2 surge, increased transmission and mortality from SARS-CoV-2, and a widening health disparity gap.

The 2021 Annual Homeless Assessment Report will not be completed and published until 2022. The 2020 AHAR was published in March of 2021 and already showed a 2% increase from 2019 to 2020. What will the 2021 AHAR reveal?