Nursing Homes Want Docile

The US population is aging. Between 2005 and 2015, the percentage of the population over 65 increased by 30%. “Older people now account for one in seven Americans: almost 50 million people, over 26 million women and over 21 million men.” As our population ages, the number of individuals with debilitating conditions like dementia is also increasing. By 2050, it has been estimated that as many as 15 million Americans could have Alzheimer’s. And in an average week, nursing facilities in the U.S. currently administer antipsychotic medications to over 179,000 people “who do not have diagnoses for which the drugs are approved.”

An extensive Human Rights Watch report, “They Want Docile,” described the inappropriate use of antipsychotics in older people with dementia in U.S. nursing facilities. The report found these dangerous medications were used without valid medical reasons, for the convenience of the staff, and without informed consent. Their use was often inconsistent with federal regulator requirements for the nursing facility industry. “They Want Docile” quoted a state inspector with a long career in long-term care as saying: “I see way too many people overmedicated. The doctor signs off and the nurse fills the prescription. They see it as a cost-effective way to control behaviors.”

Older people receive long-term care in various settings ranging from at home to institutional facilities. In-between settings like assisted living facilities, senior housing and retirement communities also exist. “The proportion of people living in institutional settings increases with age because care needs become more intensive.” Of the 6 million older people who receive long-term care around 4 million receive that care at home. Another 1.2 million live in nursing facilities and around 780,000 people live in other residential care communities.

The nursing facility industry is big business and Medicare and Medicaid is the financial foundation that supports it. “In 2015, the nursing facility industry, assisted living, and other types of long-term care recorded annual revenues of $156.8 billion, 41 percent of which came from Medicaid and 21 percent from Medicare.” The Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987 requires the nursing facility industry to meet certain standards, including certification of the care facility, to be paid by Medicare and Medicaid. CMS, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, contracts with state agencies to certify facilities and to guarantee “substantial compliance.”

With the growth in older populations and the increases in debilitating conditions such as dementia, the need for long-term care and support services will grow rapidly. Although some forms of dementia have earlier onset, the disease is associated with older age: increasing age is the “greatest known risk factor” for Alzheimer’s disease. Experts estimate that approximately 70 percent of people aged 65 and over will require long-term services and support, ranging from limited support in their own homes and communities to around-the-clock care in institutional settings.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has “Practice Guidelines” for the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia that indicated they should only be used as a last resort to minimize the risk of violence, patient distress and care giver burden. The APA then referenced two studies finding “the benefits of antipsychotic medications are at best small.” Contrary to these guidelines, nursing facility staff, individuals living in facilities, their families and others told Human Rights Watch “antipsychotic drugs are used sometimes almost by default for the convenience of the facility, including to control people who are difficult to manage.”

One facility social worker said that one of the most common “behaviors” leading to antipsychotic drug prescriptions was someone constantly crying out, “help me, help me, help me.” An 87-year-old woman reflected that at her prior facility, which gave her antipsychotic drugs against her will, “they just wanted you to do things just the way they wanted.” A social worker who used to work in a nursing facility said the underlying issue is that “the nursing homes don’t want behaviors.”

Among the people living in nursing homes interviewed by Human Rights Watch, a 62-year-old woman reported she had been given Seroquel without her knowledge or consent. She said it knocked her out; leading her to sleep all the time. She claimed the facility would crush and mix it in her food so she would refuse to eat food she suspected of having the drug. “Ms. D continued to object as well as she could to being administered antipsychotic drugs until her discharge from the nursing facility the day after Human Rights Watch interviewed her.”

Madeline C., an 87-year-old woman in a facility in Illinois, described the effect of antipsychotic medications administered in a prior nursing facility. She had been placed in a dementia unit. The woman said that when she “just about went crazy” from being in a locked unit with no activities, she “started speaking out, saying things were not right.” After that, she said, “suddenly I was very sleepy,” adding, “you feel like you’re going to die there.” She said she later learned that the facility had given her an antipsychotic drug. At the time of the interview, the woman was in a different facility that had discontinued the drug. “The fog lifted…. There’s the old Madeline again.” Being at the prior facility was “a very traumatic time.”Alma G., the sister and power of attorney of Mariela O., an 84-year-old woman with dementia who died in 2017, said that her sister’s nursing facility gave her an antipsychotic drug to ease the burden of bathing her. She said, “They give my sister medication to sedate her on the days of her shower: Monday, Wednesday, Friday—an antipsychotic. They give her so much she sleeps through the lunch hour and supper.”

“They Want Docile” described many additional examples of the misuse of antipsychotic medications at nursing facilities. The authors said many of their interviews supported the statement that antipsychotic medications were often given to nursing home residents for no valid reason. Some nursing home staff told Human Rights Watch antipsychotics were prescribed for screaming or calling out. A long-term care pharmacist said he regularly sees medication requests without an appropriate diagnosis—things like “‘Seroquel for dementia,’ or ‘Seroquel for anxiety,’ or ‘Seroquel for behavior dysfunction.’”

The report is disturbing and I’ve only scratched the surface of what it describes. It also had several recommendations to federal and state legislatures, and agencies. Here are just a couple. The CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) should strengthen the enforcement of existing regulatory requirements to end all inappropriate use of antipsychotics in nursing facilities, including when their use would amount to being used as a “chemical restraint.” It should also strengthen enforcement of existing regulatory requirements for informed consent and appropriate medication administration. Care planning should include the right of patients to refuse treatment; to be involved in their care planning; to be free from unnecessary drugs and chemical restraints. Medicaid fraud units should be required to investigate and prosecute abuse, including the use of chemical restraints, and neglect in nursing facilities.”

The Washington Post published an article, Why are nursing homes drugging dementia patients without their consent?, that was written by an individual who was part of the Human Rights Watch research. She noted how the use of antipsychotics as chemical restraints in nursing homes has a long history. A 1975 Senate report documented some of the same issues occurring today. While there are federal regulations stating residents have the right to be fully informed of their treatment and even to refuse treatment, nursing homes regularly ignore the rules because they are rarely held accountable.

Human Rights Watch found that in 97 percent of citations for violations related to antipsychotic drugs, the incidents were determined to have caused “no actual harm” to residents. As a result, in almost no cases did the government impose financial penalties, which correspond to the severity of harm caused by the noncompliance. The prospect of enforcement actions, and the rare sanctions issued, unsurprisingly had little deterrent effect, our analysis found. Nursing homes cited for antipsychotic-drug-related issues did not reduce their rates of drug use any more than facilities not cited.

Further limitations on holding nursing facilities accountable have ironically come as a result of the Trump administration’s Patient’s Over Paperwork deregulatory efforts. In response to an industry request, the instances in which inspectors can assess the heaviest fines was limited. That guidance now favors one-time sanctions rather than per-day sanctions, leading in many cases for facilities to face less significant consequences. And since November of 2016, “CMS imposed an 18-month moratorium on Obama-era revisions to some regulations — not updated since 1991 — intended in part to protect residents whose psychotropic medications are prescribed on an “as needed” basis.”

A JAMA Psychiatry study showed how a peer comparison letter could reduce off-label prescribing of an antipsychotic in older adults. The researchers found that “a peer comparison letter randomized across the 5055 highest Medicare prescribers of the antipsychotic quetiapine fumarate [Seroquel] reduced prescribing for at least 2 years.” The effects were larger than those found with large-scale behavioral interventions, possibly because the content of the peer letter “mentioned the potential for a review of prescribing activity.” Writing for Mad in America about the study, Bernalyn Ruiz said:

This study provides some hopeful evidence that a simple intervention that can reach a large group of prescribers effectively. Given the high rates of overprescribing, especially within this vulnerable population, effective ways of addressing this issue are needed.

In another article reflecting on the study by Ina Jaffe for NPR, Dr. Helen Kales, the head of the University of Michigan’s Program for Positive Aging, said stopping the overmedication of dementia patients was just the beginning. She pointed out how the use of mood stabilizers with dementia patients has also accelerated. “So any kind of fixation on one [drug] — it’s maybe winning the battle, but not the war.” Dr. Kales chaired an international committee of dementia specialists who published a consensus statement on the ways to treat dementia behaviors like agitation and wandering, and said it’s better to find out what triggers the behavior or modify the patient’s environment instead of prescribing medication. “The highest ranked and endorsed treatments are all non-pharmacological approaches.”

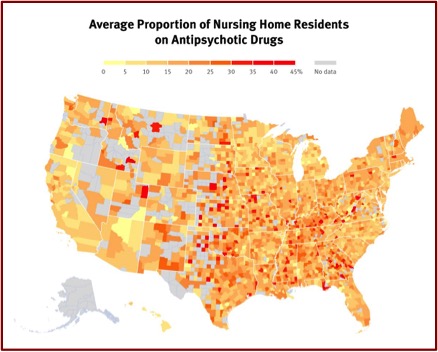

In closing, consider the following. The graphic below by Human Rights Watch shows the proportion of nursing home residents across the U.S. on antipsychotic drugs. The more intensely red areas indicate a higher percentage of antipsychotic use, with 45% being the highest. If you or a loved one were in a nursing home somewhere in the U.S. would you want it to be using antipsychotics to chemically manage you and your behavior?