The Long Strange Trip of MDMA-Assisted Therapy

The FDA accepted a new drug application (NDA) by Lykos Therapeutics for MDMA-assisted therapy in February 2024. Lykos was formerly known as MAPS PBC (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, Public Benefit Corporation) and MAPS had been doing research and collecting clinical trial data on MDMA-assisted therapy for over two decades. The founder and President of MAPS, Rick Doblin, optimistically said one of his primary motivations for founding MAPS was to bring psychedelic-assisted therapies to market as FDA-approved treatments. He hoped the potential approval of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD would only be the first of many psychedelic-assisted therapies that become available. But in August of 2024, the FDA officially rejected the Lykos request to approve MDMA-assisted therapy.

NPR reported the FDA asked Lykos to further study the safety and efficacy of the treatment. An FDA spokesperson said there were “significant limitations to the data contained in the application that prevented the agency from concluding the drug is safe and effective for the proposed indication.” Lykos’ CEO Amy Emerson said the request for another Phase 3 trail was “deeply disappointing” and “would take several years.” She thought many of the requests from the FDA could be addressed with existing data, post-approval requirements “or through reference to the scientific literature.” Lykos said it planned to request a meeting with the FDA to reconsider the decision.

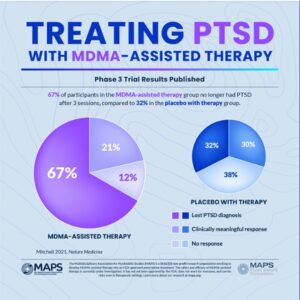

An article on Nature about the FDA rejection said many researchers were surprised by the decision. But I don’t think it wasn’t an entirely unanticipated decision. In June, an independent advisory committee overwhelming voted against approving MDMA, citing problems with the clinical trial design that made it difficult to determine the drug’s safety and efficacy. One concern was that around 90% of the participants in Lykos’ trials guessed correctly whether they had received the drug or placebo.

Another problem was the Lykos approach of giving the drug alongside psychotherapy. Rick Doblin had previously stated in an interview on Fox Business that he thought the drug’s effects was inseparable from guided therapy which was the main change agent: “It’s not the drug itself; it’s the therapy that is the primary act of treatment.” He thinks MDMA makes the therapy more effective. The Nature article said:

MDMA is thought to help people with PTSD be more receptive and open to revisiting traumatic events with a therapist. But because the FDA doesn’t regulate psychotherapy, the agency and advisory panel struggled to evaluate this claim.

One expert said it was like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. But even he was “a little surprised” by the agency’s decision. The FDA’s decision could affect future applications for other psychedelics—such as psilocybin and LSD—that are currently in late-stage trials for treating psychiatric disorders. An anaesthesiologist at Stanford who studies psychedelics doubted that other companies developing these drugs will include a psychotherapy component in their application submission to the FDA. The respective effects of the interventions are difficult to untangle from the drug.

Data Integrity Problems

Medscape reported in June that the FDA’s Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee found the benefits of MDMA-assisted therapy did not outweigh the risks. Only two of 11 members thought Lykos had proved the treatment’s effectiveness. “In a second vote, only one panelist agreed the benefits outweighed the risks.” The committee’s chairperson was not convinced MDMA was effective. He said he and others on the panel thought the “functional unblinding” in Lykos’ two pivotal trails was concerning.

The FDA advised Lykos in 2016 to consider using an active comparator instead of placebo to minimize bias and functional unblinding, but the company rejected the FDA’s suggestions, said David Millis, MD, the lead reviewer from the FDA’s Division of Psychiatry.

Some members of the committee said it was difficult to differentiate from the trial design whether therapy had any impact over and above MDMA. One person said: “The way it’s presented in the application makes it impossible to untangle the two.” Another commented how the therapy element was “a bit of a black box.” They were also concerned about financial and other conflicts if Lykos were solely responsible for training therapists. In STATS News, Thomas Insel, the former director of the NIMH, commented:

Administration of MDMA within the context of psychotherapy might constitute best practice, and might confer effectiveness and safety that is profoundly different from taking the same drug at a rave or outside of a therapeutic environment. But the FDA approval process — optimized for drugs used in other areas of medicine — is not really adapted for psychiatric medications in which “the world does its bit.” Indeed, a regulatory approach that looks at psychiatric medications without attention to such powerful psychological interventions as exposure and cognitive therapy is not aligned with the research showing that the combination of medication and psychotherapy is preferable to either intervention alone.

During the public hearing on the MDMA-assisted therapy proposed by Lykos, a psychology PhD candidate noted the core idea of the therapy was that humans have “an inner healing intelligence” that is accessed through MDMA and other non-ordinary states of consciousness. She observed the Lykos therapy manual “is based on New Age psychospiritual theory.”

Some companies, such as Compass Pathways in London, which is conducting a Phase III trial of psilocybin for depression, do not have psychotherapy as a component of the trial. Atai Life Sciences in Berlin is excluding anyone who recently started psychotherapy from participating in its trial of the psychedelic DMT (dimethyltryptamine) for depression. However, studying the effects of psychedelics independent of the psychotherapy goes against the traditional method of guided trips dating back to 1950s experiments of LSD to “treat” alcoholism. See “Bill W. and his LSD Experiences,” Part 1 and Part 2.

Nature also reported that the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review alleged that Lykos therapists pressured study participants to report only positive results. The Institute said Lykos employees’ advocacy for the drug affected the participants’ judgement. Oh, and then there was a report that an unlicensed therapist working for MAPS at a trial site in Canada was sued for sexually assaulting a participant who was under MDMA’s influence.

MDMA Papers Retracted and Lykos Reorganizes

These issues were known by the researchers who published three papers, but they turned a blind eye to them and published research papers touting the positive effects of MDMA-assisted therapy without mentioning the concerns. One of the researchers even admitted there were potential problems with the proposed treatment process, including the expense and time needed; and the potential for addiction. Psychologist James Coyne thought there had been a well-orchestrated publicity campaign on the research done by MAPS. See “Don’t Roll the Dice with MDMA,” Part 1 and Part 2.

One day after the FDA’s rejection of Lykos’ NDA for MDMA, the journal Psychopharmacology retracted three papers about MDMA-assisted therapy. Many of the authors of the three studies, including Rick Doblin and Lykos CEO Amy Emerson, are affiliated with MAPS and Lykos. According to the retraction notice for the one of the retracted papers,

The Editors have retracted this article after they were informed of protocol violations amounting to unethical conduct at the MP4 study site by researchers associated with this project. The authors have subsequently confirmed that they were aware of these violations at the time of submission of this article, but did not disclose this information to the journal or remove data generated by this site from their analysis. Additionally, the authors also did not fully declare a potential competing interest. Several of the authors are affiliated with either the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) or MAPS Public Benefit Corporation (MAPS PBC), a subsidiary that is wholly owned by MAPS. As is stated in the Funding declaration, MAPS fully funded and provided the MDMA that was used in this trial, and MAPS PBC organised the trial.

Then on August 15th, Lykos announced it was laying off 75% of its workforce and Rick Doblin also resigned his position on Lykos’ board. In a news release from Lykos, he said: “After 38 plus years of work, I’m profoundly saddened by the FDA decision around this critically needed therapy, but am heartened that Lykos will still move forward continuing clinical research that addresses the FDA’s questions.” He added the FDA delays made it more important than ever that he work at MAPS to develop global access to MDMA and other psychedelics.

Lykos will continue to pursue its goal of FDA approval of MDMA-assisted therapy. While Lykos was announcing its restructuring plans, the company also announced that David Hough has been appointed to oversee Lykos’ resubmission of MDMA treatment to the FDA. When Hough was with Janssen, he led the development team that brought Spravato (esketamine) to market to treat major depression and treatment-resistant depression. See “Red Flags with Spravato” and “Doublethink with Spravato?” for more information on esketamine.

Conclusions

Let’s hope that if there is a meeting between Lykos and the FDA, that Lykos won’t attempt to present research or data they know is tainted by protocol violations again. And look for the FDA to re-examine the “existing data” from Lykos for MDMA-assisted therapy for any additional undetected or undisclosed problems. Amy Emerson may be disappointed in the FDA rejection, but MAPS and Lykos should have been less slipshod in their research. If it takes years before the credible research can be done, we’ll just have to wait.