Rick Doblin, the founder and Executive Director of MAPS, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, was interviewed on Fox Business in January of 2023. He announced that the MAPP2 clinical trial study was completed in November of 2022 and had achieved its objectives. With two confirmatory Phase 3 Trials now completed, Doblin thought it “quite likely” the FDA will approve MDMA-assisted therapy by May of 2024. He predicted the significance FDA approval of MDMA-assisted therapy would be for the “whole field of psychedelic-assisted therapy” (i.e., for psilocybin, ibogaine, ayahuasca, mescaline and others). He added that MDMA was a therapy drug in the 1970s before it became the party and “rave” drug, ecstasy.

In the interview, Doblin emphasized that it was therapy that was main change agent. “It’s not the drug itself; it’s the therapy that is the primary act of treatment. And the MDMA makes the therapy more effective.” Don’t miss what he is saying—the therapeutic process is the primary treatment and the MDMA facilitated the therapy. Nevertheless, the results reported in the MAPS studies were dramatic.

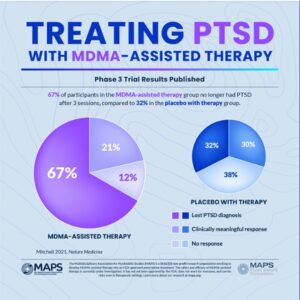

In Mapp1, 67% of the participants in the MDMA-assisted group “no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis” after three treatment sessions. Another 21% had a clinically meaningful response, adding up to 88% of participants in the MDMA-assisted therapy group experienced a clinically meaningful reduction in symptoms. These participants also had statistically significant reductions in functional impairment relative to the placebo group with therapy. However, 32% of the placebo with therapy group also no longer met the criteria for PTSD. This percentage of change in the placebo group underscores the importance of the therapy as the primary change agent emphasized by Doblin. See the following graphic.

The results of the MAPP1 clinical trial were published in Nature Medicine, “MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD” and provide a more detailed examination of the data underlying the Phase 3 trail results reported in the above graphic.

The study abstract reported the standard methodology used in the study as “randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled” and that the placebo itself was inactive. The small number of participants in the study groups was also noted. There were 42 individuals in the MDMA-assisted group and 37 individuals in the placebo group. Turning to the celebrated primary endpoint of the study being met by 67% of the study participants, there were only 28 participants who no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. The researchers acknowledged that the participant population was smaller than originally planned, which they attributed to the pandemic. They then pointed to the results, saying “given the power noted in the study, it is unlikely that population size was an impediment.” Really?

The FDA described how researchers should design clinical trials to answer specific research questions for a medical product here, saying “Clinical trials follow a typical series from early, small-scale, Phase 1 studies to late-stage, large scale, Phase 3 studies.” Phase 3 clinical studies, like MAPP1 And MAPP2 were recommended to contain 300 to 3,000 participants who have the condition; and the length of study to be 1 to 4 years. The MAPP1 study only had 79 participants; and the length of the study was only 18 weeks. The Procedural timeline in “MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD” said: “Following the screening procedures and medication taper, participants attended a total of three preparatory sessions, three experimental sessions, nine integration sessions and four endpoint assessments (T1–4) over 18 weeks, concluding with a final study-termination visit.”

The double-blindedness of the study was also neutralized by using an inactive placebo, given the psychoactive properties of MDMA. Participants as well as the researchers and others who assisted in the study (i.e., the trained therapy team) would know in which study group the “blinded” participants were in by observing participant’s behavior after they ingested the supposedly unknown substance. This limitation was acknowledged by the researchers:

Given the subjective effects of MDMA, the blinding of participants was also challenging and possibly led to expectation effects. However, although blinding was not formally assessed during the study, when participants were contacted to be informed of their treatment assignment at the time of study unblinding it became apparent that at least 10% had inaccurately guessed their treatment arm. Although anecdotal, at least 7 of 44 participants in the placebo group (15.9%) inaccurately believed that they had received MDMA, and at least 2 of 46 participants in the MDMA group (4.3%) inaccurately believed that they had received placebo.

Anecdotally then, 95% of the MDMA-assisted group (44 of 46) and 84% of the placebo group (37 of 44) were able to accurately state which research group they were in. The double-blind methodology was clearly ineffective and the dramatic results reported by the study should be understood with this in mind. Emphasizing the differences between the MDMA-assisted group and the placebo group for the lost PTSD diagnosis and a clinically meaningful response draws the readers attention away from these damning limitations for a Phase 3 clinical trial study: the miniscule population size and the failure to use a legitimately double-blinded study methodology.

The MAPP2 Clinical trial was completed on November 2, 2022, and MAPS announced the results on November 17, 2022. The primary and secondary endpoints for the MAPP1 and MAPP2 studies were the same. However, MAPP2 enrolled participants with moderate and severe PTSD, where MAPP1 only enrolled participants with severe PTSD. It had 104 participants.

The results for MAPP2 are expected to be in a peer-reviewed journal sometime in 2023: “The full data from MAPP2, expected to be published in a peer-reviewed journal later this year [2023], will support MAPS PBC’s new drug application to be filed with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).” MAPP2 treated its 104 participants “living with PTSD with either MDMA-assisted therapy or placebo with therapy.” The results were said to confirm the findings from MAPP1, with no serious adverse events observed among the participants. Rick Doblin was quoted as saying:

When I first articulated a plan to legitimize a psychedelic-assisted therapy through FDA approval, many people said it was impossible. Thirty-seven years later, we are on the precipice of bringing a novel therapy to the millions of Americans living with PTSD who haven’t found relief through current treatments. The impossible became possible through the bravery of clinical trial participants, the compassion of mental health practitioners, and the generosity of thousands of donors. Today, we can imagine that MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD may soon be available and accessible to all who could benefit.

MAPS went on to give a brief history of where MDMA had been legally used in therapy for a decade before it was “criminalized” (i.e., classified as a Schedule 1 Controlled Substance) in 1985. MAPS was founded the next year “to fund and facilitate research into the potential of psychedelic-assisted therapies; educate the public about psychedelics for medicine, social, and spiritual use; and advocate for drug policy reform.” The publication of the MAPP1 clinical trial was said to be a major milestone. MDMA-assisted therapies are being planned or conducted to evaluate “conditions closely related to PTSD” such as substance use disorder and eating disorders. Trials of other therapies with couples and group therapy among Veterans are also being planned or conducted.

“These additional Phase 2 trials will determine if MDMA-assisted therapies may be effective for other conditions or with other treatment modalities commonly used to address PTSD.”

Psychiatrist.com echoed these expectations if the FDA approves MDMA-assisted therapy, adding that approval would enable the exploration of the drug’s benefit for depression, anxiety, substance-use disorders, autism spectrum disorder, and compulsive disorders. The lead author of “MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD” described for Psychiatrist.com how MDMA acts on the amygdala, the part of the brain that processes fear-related memories and facilitates memory retrieval. When used in a clinical setting (i.e., with therapy), “they say it helps untangle, consolidate, and release deeply-ingrained memories that may have been suppressed.” MDMA also facilitates the release of oxytocin, a hormone that makes you feel self-compassion and connected to others. The end result is MDMA helps create an environment in which “participants take comfort in their therapy team, approach their memories from a different lens, and ultimately begin to heal.”

This description of MDMA and oxytocin needs to be nuanced, as it glosses over some of the not-so positive connections made with the release of oxytocin. In “The two faces of oxytocin,” the American Psychological Association said recent research has shown that oxytocin is part of a response to social separation and related stress. When it operates during times of low stress, oxytocin physiologically rewards people with good social bonds with feelings of well-being. However, it may “lead people to seek out more and better social contacts” during times of high social stress or pain. This two-faced context for MDMA facilitating the release of oxytocin again underscores the importance of the therapeutic aspect of MDMA-assisted therapy.

Should the FDA approve MDMA-assisted therapy? Should we roll the dice and see what happens? A recent survey noted Americans have mixed feelings. According to the UC Berkeley Psychedelics Survey, 61% of registered American voters support legalizing regulated therapeutic access to psychedelics. Thirty-five percent of those supporters said they strongly support such action.

And yet, there were 35% who opposed it, with 61% also saying they do not see psychedelics as “good for society” and 69% who don’t think psychedelics are something they would personally use. “The data suggested voters are open to policy change but also have significant reservations.”

A reliable answer to whether the FDA should approve MDMA-assisted therapy is hampered by the Schedule I classification of psychedelics, which creates multiple hurdles that researchers have to get over in order to investigate their therapeutic value. And further, it seems supporters of psychedelic-assisted therapies are following a strategy taken from the playbook of legalizing recreational marijuana—focus on the legalization of psychedelics one state at a time. More on this in Part 2.