The Unseen Surge of Alcohol Use

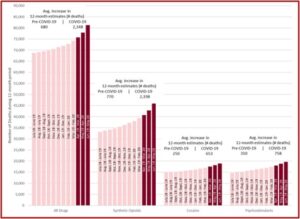

Although the increase in overdose deaths preceded the COVID pandemic, the pandemic seems to have accelerated the trend. In December of 2020, the CDC reported that drug overdose deaths in the U.S. rose 29.4% that year, mostly from illicitly manufactured fentanyl. Overdose deaths involving psychostimulants increased 10 times from 2009 to 2019. This increase was a mixture of opioids and psychostimulants as well as psychostimulants alone. But all the attention on these two drug classes seems to have overlooked the unseen surge of COVID-related increases with another drug—alcohol.

Using death certificate data from the National Center for Health Statistics, White et al found that almost 1 million people died from alcohol-related causes between 1999 and 2017. The number of death certificates mentioning alcohol more than doubled during that time frame. The Director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), George Koob, said:

Alcohol is not a benign substance and there are many ways it can contribute to mortality. The current findings suggest that alcohol-related deaths involving injuries, overdoses, and chronic diseases are increasing across a wide swath of the population. The report is a wakeup call to the growing threat alcohol poses to public health.

The researchers found that nearly half of alcohol-related deaths were from liver disease (31%) or overdoses on alcohol alone or with other drugs (18%). By the end of the study, alcohol-related deaths were increasing among people in almost every age, racial and ethnic group. Death rates increased for women (85%) more than men (35%). Women also appeared to be at a greater risk for several alcohol-related consequences than men—including cardio-vascular disease, liver disease, alcohol use disorder. Dr. Koob said:

Taken together, the findings of this study and others suggests that alcohol-related harms are increasing at multiple levels – from ED visits and hospitalizations to deaths. We know that the contribution of alcohol often fails to make it onto death certificates. Better surveillance of alcohol involvement in mortality is essential in order to better understand and address the impact of alcohol on public health.

The researchers said alcohol-related deaths were highest among males, individuals between 45 and 74 years of age, and non-Hispanic American Indians or Alaska Natives. Rates increased for all age-groups except 16 to 20 and 75 and over. The largest increase was among non-Hispanic White females. These findings confirm the increasing burden of alcohol on public health.

On his blog, William White observed how the alarm over recent drug surges with opioids and methamphetamines could be obscuring surges in alcohol consumption and its related consequences. In addition to the White et al study, William White also referred to Sherk et al, whose researchers found that even light or moderate alcohol consumption increased the risk for a number of health consequences, including cancer, heart disease and traumatic injuries. More than one quarter (27%) of alcohol-related hospital stays were experienced by individuals who drank within the weekly guidelines.

The low-risk drinking guidelines for men were no more than 14 drinks per week and no more than 4 drinks per day. Low risk guidelines for women were no more than 7 drinks per week and no more than 3 drinks per day. Sherk et al concluded drinkers who followed weekly low-risk drinking guidelines were not immune from harm. They suggested guidelines of one drink per day for both sexes. The researchers clearly demonstrated that alcohol abuse and the related consequences were increasing before the COVID pandemic.

Alcohol Abuse and COVID

As stay-at-home orders began in some US states to lessen COVID-19 transmission in March of 2020, Nielsen reported a 54% increase in national sales of alcohol for the week ending Mach 21, 2020. The World Health Organization warned that alcohol use could potentially worsen health vulnerability, risk-taking behaviors, mental health issues and violence. The WHO suggested existing rules and regulations to protect health and reduce the harm caused by alcohol, such as restricting access, should be reinforced during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Any relaxation of regulations or their reinforcement should be avoided.”

Pollard, Tucker and Green looked at “Changes in Adult Alcohol Use and Consequences During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US.” The data were collected using the RAND Corporation American Life Panel (ALP), a nationally representative, probability-sample panel of 6,000 participants. A sample of 2,615 ALP members ages, 30-to-80, were invited to participate in the baseline survey.

Comparisons before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were made on the number of days participants reported any alcohol use and heavy drinking, and the average number of drinks consumed over the previous 30 days. Heavy drinking was defined as 5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more drinks for women within a couple of hours. Adverse consequences were assessed by the 15-item Short Inventory of Problems associated with alcohol use in the previous 3 months. Comparisons were made overall, and across self-reported sex, age, and race/ethnicity.

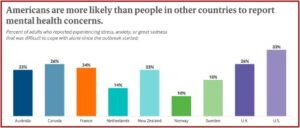

These data provide evidence of changes in alcohol use and associated consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to a range of negative physical health associations, excessive alcohol use may lead to or worsen existing mental health problems, such as anxiety or depression, which may themselves be increasing during COVID-19. The population level changes for women, younger, and non-Hispanic White individuals highlight that health systems may need to educate consumers through print or online media about increased alcohol use during the pandemic and identify factors associated with susceptibility and resilience to the impacts of COVID-19.

It does seem that concern with overdoses from opioids and methamphetamine in the midst of COVID overshadowed the growing problem with increasing alcohol consumption and its related consequences during the pandemic. William White observed that alcohol use is historically pervasive in the U.S. and “so infused into the cultural water in which we all swim that we fail to see it. That blindness has exacted, and continues to exact, an enormous toll on individuals, families, and communities.” The findings of the above discussed research studies reinforce the need for continued efforts with public and professional alcohol-related education, alcohol treatment resources, screening for alcohol problems and recovery support for individuals and families effected by alcohol use disorders. We cannot let concerns with the pandemic or opioid epidemic draw our attention away from the growing problem with alcohol-related deaths.