Sigmund Freud was a Cocaine Evangelist and Addict

So here is the continuing story on Sigmund Freud and cocaine begun in “Raising the Stakes in the War on Cocaine Addiction.” To give a quick recap, Freud began experimenting with cocaine in April of 1884. He used it to treat depression, saying it was a “magic drug.” He hoped that with his help cocaine could “win its place in therapeutics by the side of morphine.”

So here is the continuing story on Sigmund Freud and cocaine begun in “Raising the Stakes in the War on Cocaine Addiction.” To give a quick recap, Freud began experimenting with cocaine in April of 1884. He used it to treat depression, saying it was a “magic drug.” He hoped that with his help cocaine could “win its place in therapeutics by the side of morphine.”

According to Paul Vitz, Freud’s evangelism of cocaine seems to have been driven by three things:

- his intense desire to get married to his fiancée and fear of losing her (a separation anxiety, in Freudian terms);

- his drive to become a medical success story in championing the positive effects of a new drug, thus advancing his career and financial prospects (so he could marry); and

- to treat his personal struggle with depression (largely induced by his separation anxiety).

When describing his personal experiences in treating his depression with cocaine, Freud said he felt “exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which in no ways differs from the normal euphoria of the healthy person.” He saw an increase in his self-control and capacity for work. He had no unpleasant after effects, as with alcohol and “absolutely no craving” for more cocaine, even after repeated use. “In other words, you are simply normal, and it is soon hard to believe that you are under the influence of any drug.”

He recommended cocaine to family, friends and professional colleagues alike. A friend of Freud’s, Dr. Ernst Fleischl became addicted to morphine while attempting to treat a painful neurological disease. Freud attempted to counteract his morphine addiction with cocaine. At first, cocaine was a helpful substitute for the morphine.

But Fleischl had to increase his cocaine dose as tolerance set in. After one year of cocaine use he was taking a full gram of it daily—TWENTY TIMES the dose Freud personally used. Fleischl was now dually addicted to opiates and cocaine. He soon developed a full-fledged cocaine psychosis, with visions of “white snakes creeping over his skin.”

Freud and other physician friends had little success in weaning Fleischl from his drug use. By June of 1885, Freud thought his friend had about six months to live. Fleischl remained alive for another six pain-filled years. Freud later acknowledged he might have hastened his friend’s death, by “trying to cast out the devil with Beelzebub.”

In July of 1885 a German authority on addiction began publishing a series of articles on cocaine as an addictive drug. A friend of Freud’s, originally favorable towards cocaine, reported that it produced severe mental disturbances. One prominent doctor said Freud had unleashed “the third great scourge of mankind.” The first two were opium and alcohol.

By 1890, the addictive and psychosis producing nature of cocaine was well documented. Freud had moved on in his search for fame and fortune to other interests. And when he co-authored Studies on Hysteria with Joseph Breuer in 1895, psychoanalysis was born. However, Freud continued to use and prescribe cocaine until at least 1896.

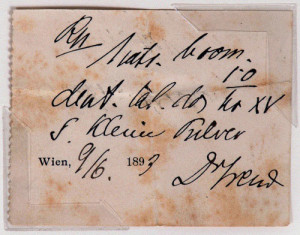

A handwritten prescription for a “white powder”, signed by Sigmund Freud in 1893, is evidence of his continued cocaine use. In 2004, Robert Edwards Auctions sold this prescription for $2,875.

Freud’s letters to a friend and fellow cocaine user, Wilheim Fleiss, contained several references to his ongoing cocaine use. On January 24, 1895, Freud described to Fleiss how a “cocainization” of his left nostril helped him to an amazing extent. He wrote on April 20, 1895 that he pulled himself out of a miserable (depression?) attack with a cocaine application. On June 12th, 1895, Freud wrote: “I need a lot of cocaine.”

Several scholars have debated whether Freud’s use of cocaine influenced his developing theories. Both Fredrick Crews and E. M. Thornton have argued that Freud’s use of cocaine had a significant influence on his developing theories, especially their emphasis on sex. Thornton claimed that Freud’s psychological theory was the natural outcome of his extensive cocaine usage.

Paul Vitz took a more nuanced approach in Sigmund Freud’s Christian Unconscious, stating that much of Freud’s psychology was evident before he began using cocaine. Freud’s cocaine use may have contributed to sloppy thinking at times. It could have contributed to his preoccupation with sex, or made his depressions darker and more difficult to fight. “But cocaine did not create the primary content and structure of Freud’s mind and thought.”

Yet Thorton presented some rather convincing evidence of Freud’s cocaine “problem” and its potential influence on his theories. Freud himself said that psychoanalysis began with his research into hysteria: “The Studies on Hysteria by Breuer and myself, published in 1895, were the beginnings of psycho-analysis.” Freud began to have heart problems (one of the side effects of cocaine abuse) early in 1894. He suffered from “fainting” spells—four of which were publically witnessed by others. He had an obsession with dreams; some paranoid traits and a tendency towards grandiosity.

In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud recounted a dream he had in 1895 where he saw a patient with scabs on her turbinal bones, which recalled a worry he had about his own health:

At the time I frequently used cocaine in order to suppress distressing swellings in the nose, and I had heard a few days previously that a lady patient who did likewise had contracted an extensive necrosis of the nasal mucous membrane. In 1885 it was I who had recommended the use of cocaine, and I had been gravely reproached in consequence. A dear friend, who had died before the date of this dream, had hastened his end by the misuse of this remedy.

By 1895 Freud had probably been using cocaine (nasally) for over two years. Physically, the effects of this heavy usage would have been essentially identical to the catalogue of symptoms noted by Fleiss as those for “nasal reflex neurosis” (headache, vertigo, dizziness, acceleration and irregularity of the heart, respiratory difficulties, etc.). So the physical problem that Freud treated with cocaine (nasal reflex neurosis) was essentially caused by his use of cocaine.

His paranoia was evident in the public breakups he had with formerly close associates like Breuer—with whom he wrote Studies in Hysteria (1894), Fliess (1900), and Jung (1913). Freud’s interpretation of Jung’s dream in 1907, just after they met face-to-face for the first time, was that Jung wished to dethrone him and take his place in the psychoanalytic movement.