Christology at Chalcedon

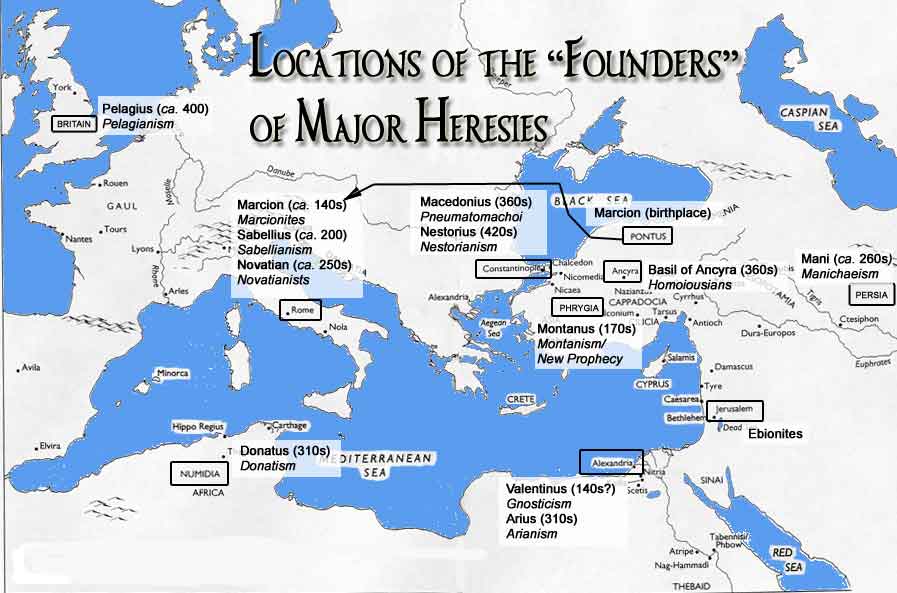

Christological debate over whether Jesus, as God incarnate, had two natures (divine and human) or only one nature continued after the Council of Ephesus in 431. Nestorianism, rejected at the Council, had said Christ had two distinct natures. But there were still two legitimate views on the natures of Christ, the Antiochene view and that held by the School of Alexandria. The Antiochene view was that Jesus possessed two natures—human and divine—that were distinct from each other, yet intimately connected. Theodoret of Cyrrhus explained this as the Word uniting Himself with flesh by clothing Himself with it and making it perfect through suffering.

Cyril and the School of Alexandria emphasized the divinity of Christ and insisted on the unity of His person, saying: “There is one nature of God the Word incarnate, but worshipped with his flesh as one worship.” They saw their stress on the unity of the incarnate Word as an important defense of the Nicene Creed and refutation of Arianism. But this stress on the unity of the nature of Christ led to Monophysitism, a doctrine holding that the incarnate Christ had only one nature, not two.

The term Monophysitism appeared in the aftermath of the Council of Chalcedon in 451 to describe all those who rejected the Council’s Definition that the incarnate Christ was one Person in two Natures. Even thought he did not articulate the Monophsysite view precisely, its seeds were present in Cyril of Alexandria’s polemic against Nestorius at the Council of Ephesus. See “Christological Conflict at Ephesus.” According to the New Dictionary of Theology: “Although safeguarding the unity of Christ’s person, the Alexandrian approach led to Monophysitism, which appealed to Cyril as its theological mentor.”

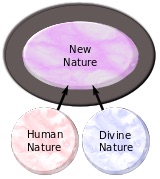

Eutyches was an avid opponent of Nestorius and supported Cyril of Alexandria at the Council of Ephesus. His vehement opposition to Nestorianism led him to an equally extreme view of Monophysitism, which resulted in Eutyches being condemned as a heretic himself. While Nestorius emphasized the distinction of the divine and human natures of Christ almost to the point of saying there were two persons—divine and human—Eutyches inverted the assertion to the opposite extreme. He held the human nature and divine nature of Christ were combined into a unique, single nature without alteration, absorption or confusion: the incarnate Word. See the following illustration of Eutyches’ view of Christ’s nature.

Eutyches was reacting to Nestorianism and leaning towards Apollinarianism. Confronted with whether he confessed two natures in the incarnate Christ, he declared “our Lord to have become out of two natures before the union. But I confess one nature after the union.” Eutyches conceived of Christ as a mingling of two natures. “In the union the divine had major share, the humanity being merged with deity as a drop of honey mingled in the ocean.” Although this was consistent with Cyril’s position, Eutyches went further, denying that Christ was consubstantial with humanity. He was trying to stress the uniqueness of Christ, not deny his full manhood.

Eutyches was reacting to Nestorianism and leaning towards Apollinarianism. Confronted with whether he confessed two natures in the incarnate Christ, he declared “our Lord to have become out of two natures before the union. But I confess one nature after the union.” Eutyches conceived of Christ as a mingling of two natures. “In the union the divine had major share, the humanity being merged with deity as a drop of honey mingled in the ocean.” Although this was consistent with Cyril’s position, Eutyches went further, denying that Christ was consubstantial with humanity. He was trying to stress the uniqueness of Christ, not deny his full manhood.

He was accused of heresy by Domnus II of Antioch and Eusebius, bishop of Dorylaeum, at a synod presided over by Flavian at Constantinople in 448. Eutyches was deposed from his priestly office and excommunicated. But he had political connections, as he was the godfather of an influential person at the court of Theodosius II. In 449 at the Second Council of Ephesus, later know as the Robber Council, Dionscorus reinstated Eutyches as a priest, believing he had repented of his beliefs. “Eusebius, Domnus and Flavian, his chief opponents, were deposed.”

Meanwhile, Emperor Theodosius II died when he fell from his horse in 450. He was succeeded by Marcian, who was a supporter of the Antiochene two natures view. Marcian agreed to convene the Council of Chalcedon in 451 to settle the debate over Jesus’ incarnate nature(s). The imperial goal was to establish a single faith throughout the Eastern Roman Empire. Instead, it ended up further dividing the church when it adopted the Antiochene view that Jesus had two distinct natures. There were only two papal legates and two North African bishops in attendance. The Western Roman Empire under Valentian at the time was preoccupied with Attila the Hun’s invasion of Gaul in 451.

If the Council of Chalcedon was to succeed, the imperial commissioners knew it had to produce a formulary that everyone would be required to sign and they made their intentions clear. But the majority of the bishops didn’t think a new creed was needed and they successfully resisted the imperial pressure to formulate one. They wanted to simply affirm “the exposition of the orthodox and irreproachable faith set forth” at the Council of Nicea in 325 and the Council of Constantinople in 381. The decisions of the 449 Second Council of Ephesus were annulled; Nestorianism and Eutychianism were condemned. After repeating the 325 Nicea and Constantinopolitan formulations of the Nicene Creed, they said:

This wise and salutary Creed, therefore, derived from divine grace suffices for the perfect acknowledgement and confirmation of godliness; for concerning the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, its teaching is complete, and to those who accept it faithfully it sets forth in addition the Incarnation of the Lord.

The Council then formulated a confession of faith, which is known as the Definition of Chalcedon. Christ was declared to be one Person in two Natures. The Divine nature was of the same substance as the Father, the human of the same substance as us. The two were “united unconfusedly, unchangeably, invisibly, inseparably.” Although its purpose was to define the limits of legitimate theological speculation on the natures of Christ rather than make an exact and final statement of a theological position, it was not universally accepted and controversy continued for the next two centuries over Monophysitism.

In opposition to Nestorius, Chalcedon affirmed the Virgin Mary as theotokos, Mother of God. The intent was to assert the true divinity of Christ, not exalt the Virgin Mary. The Eastern Church reacted negatively to the Chalcedon definition of the incarnation. Nestorians were forced further East, beyond the Roman Empire. Monophysites, who were supporters of Cyril and the Eastern Church, fought the definition and were regarded as Nestorians because of their opposition. Despite the division it caused in the East, the Definition of Chalcedon became the standard view of the incarnation in the Western church:

Wherefore, following the holy Fathers, we all with one voice confess our Lord Jesus Christ one and the same Son, the same perfect in Godhead, the same perfect in manhood, truly God and truly man, the same consisting of a reasonable soul and a body, of one substance with the Father as touching the Godhead, the same of one substance with us as touching the manhood, like us in all things apart from sin; begotten of the Father before the ages as touching the Godhead, the same in the last days, for us and for our salvation, born from the Virgin Mary, the Theotokos, as touching the manhood, one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten, to be acknowledged in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation; the distinction of natures being in no way abolished because of the union, but rather the characteristic property of each nature being preserved, and concurring into one Person and one subsistence (ὑπόστασις), not as if Christ were parted or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son and only-begotten God, Word, Lord, Jesus Christ; even as the Prophets from the beginning spoke concerning him, and our Lord Jesus Christ instructed us, and the Creed of the Fathers has handed down to us.These things, therefore, having been formulated by us with all possible exactness and care, the holy ecumenical council decrees, that it is unlawful for anyone to produce another faith, whether by writing, or composing, or holding, or teaching others.

The Definition of Chalcedon sought to put boundaries on the speculation about Christology. Reaching back to Nicea, it confirmed the Son is consubstantial with the Father; He is like the Father. Turning then to the humanity of Jesus, it affirmed He is consubstantial with us; He is like us (human) in every way. It went on to say there was a simple unity in the Son, in Jesus. Don’t confuse, mix, separate, deny or separate the two natures.

You can listen to 20-minute YouTube lecture on the Council of Chalcedon by Ryan Reeves, an Assistant Professor of Historical Theology at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.