Spiritual Gifts in the Early Church, Part 2

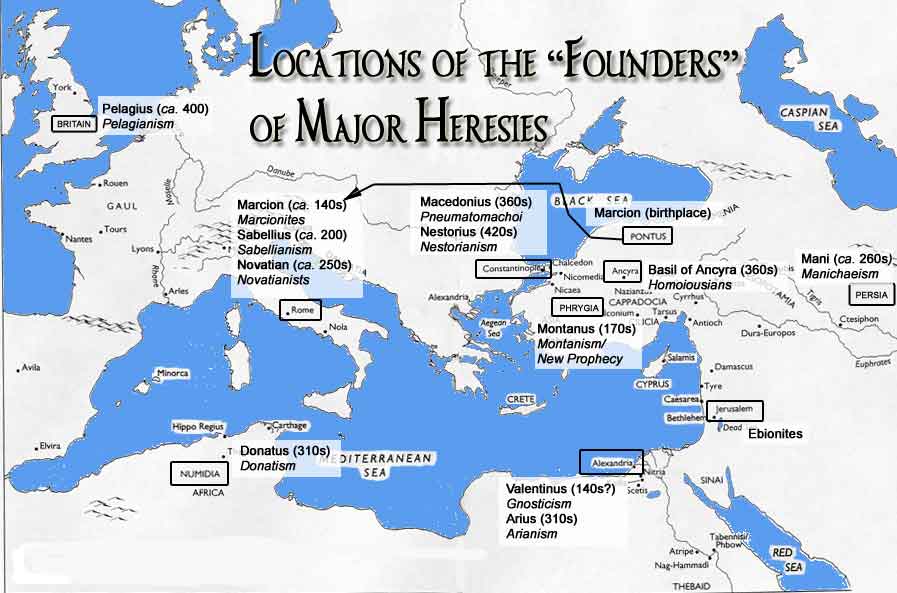

Montanism or New Prophecy began in Phrygia in 156. The movement was named after Montanus, who claimed the age of revelation continued in his own day, and that he himself was the Paraclete spoken of in John’s Gospel. He claimed to receive the gift of prophecy at his baptism, saying: “I am God almighty dwelling in man … I am neither angel or envoy; I am the Lord God and Father, and have come to myself.” Along with two prophetesses, Prisca (or Priscilla) and Maximilla, his religion was distinctive in having ecstatic outbursts, speaking in tongues and prophetic utterances. They believed these ‘oracles’ were a revelation of the Holy Spirit and could be regarded as supplementing ‘the ancient scriptures.’

While it was one of the earliest schisms or heresies in the ancient church, Montanism was still a living reality during the mid-fourth century. Eusebius (c. 260–340) and Didymus the Blind (c. 313-98) both devoted several chapters in their writings to address the dangers of Montanism. During his travels, Jerome (c. 342–420) saw Montanist communities in the western part of modern Turkey. It seems that Montanism was one of the issues that prodded the Church to give prominence to the rule of faith (See “Heresy, Canon and the Early Church, Part 2” for more on this). Although it survived attempted suppression by the Roman emperors Severus (193) and Justinian (4th century), as well as the vigorous condemnation of the church orthodoxy, Montanism died of ‘natural causes’ in the fifth century.

Nathanael Bonwetsch said primitive Montanism was: “An effort to shape the entire life of the church in keeping with the expectation of the return of Christ, immediately at hand; to define the essence of true Christianity from this point of view; and to oppose everything by which conditions in the church were to acquire a permanent form for the purpose of entering upon a longer historical development.” As the early church began to adjust to the possibility of living in the world for a considerable time with an increasingly rigid structure, there was a gradual decline in the intensity and frequency of the experience of the charismata that had been so prominent in the earlier life of the church. Jaroslav Pelikan noted in The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition that the decline in eschatological hope and the rise of the monarchical episcopate were closely related to one another.

Montanists claimed that this was a direct result of the moral decline of the church. They particularly focused their attention on the marriage ethic of the church—permitting the remarriage of widows and widowers—and a perceived laxity in fasting, as evidence of this moral decline. Along with issues of flight from martyrdom and penitential discipline, these were the principle concerns of the so–called new prophecy. “Montanism called the church to repent, for the kingdom of God was now finally at hand.” Their zeal was more characteristic of the moral reformers of the church rather than doctrinal or theological reformers.

Montanist prophetic practice had some parallels with modern charismatic practice. Specifically, when caught up in an ecstatic rapture, Montanus spoke of the Holy Spirit in the first person i.e.: “I am the Paraclete.” Although later associated with the claim of Montanus’ deity, it seemed originally to have expressed the sense of passivity as an instrument or mouthpiece of the divine. In support of this understanding, Montanus was quoted as saying: “Behold, man is like a lyre.” Montanism also claimed the source of its prophecy to be the supernatural inspiration by the Holy Spirit. The above noted emphasis on the imminent return of Christ, and attention to fasting are prominent tenets of many modern charismatic and pentecostals groups as well.

The Montanist claim that their prophecy was supernaturally inspired by the Holy Spirit caused some difficulties for the orthodox writers of the second and third centuries, who also claimed the inspiration and prophetic activity was active in the life of the church. To meet the challenge of Montanism, they shied away from taking a cessationist approach, claiming that the age of supernatural inspiration had passed. “Among the earliest critics of Montanism, there was no effort to discredit the supernatural character of the new prophecy.” Cyprian (210-258 AD), for example, argued that the church had a greater share of visions, revelations, and dreams than the Montanists. Instead, the “ecstatic seizures” of the Montanists were said to be demonic.

Hippolytus (170-235), a contemporary of Tertullian, was willing to question the continuation of prophecy—the very foundation of Montanism—more consistently than most anti-Montanist writers of the time. Noting the interweaving of a vivid eschatology with a continuing prophecy, Hippolytus frankly admitted that the church was not necessarily living in the last times. Against Montanism, he defended the process by which the church was beginning to reconcile itself to the delay in the Lord’s second coming. “As he pushed the time of the second coming into the future, so he pushed the time of prophecy into the past.” Hippolytus maintained that the Apocalypse of John was the last valid prophecy to have come from the Holy Spirit. By opposing the biblical prophets of the Old and New Testaments to the claims of the new prophets, he struck at the root of the Montanist movement. In The Refutation of All Heresies, he said the following about the Montanists:

But there are others who themselves are even more heretical in nature (than the foregoing), and are Phrygians by birth. These have been rendered victims of error from being previously captivated by (two) wretched women, called a certain Priscilla and Maximilla, whom they supposed (to be) prophetesses. And they assert that into these the Paraclete Spirit had departed; and antecedently to them, they in like manner consider Montanus as a prophet. And being in possession of an infinite number of their books, (the Phrygians) are overrun with delusion; and they do not judge whatever statements are made by them, according to (the criterion of) reason; nor do they give heed unto those who are competent to decide; but they are heedlessly swept onwards, by the reliance which they place on these (impostors). And they allege that they have learned something more through these, than from law, and prophets, and the Gospels. But they magnify these wretched women above the Apostles and every gift of Grace, so that some of them presume to assert that there is in them a something superior to Christ.

The church began to find its most trustworthy guarantees of the presence and functioning of the Holy Spirit in the threefold apostolic authority taught by Irenaeus rather than the ecstasy and prophecy that the Paraclete supposedly granted to the Montanists. The adoption of this threefold norm for the church’s life and teaching fundamentally altered the conception of the activity of the Holy Spirit that had figured prominently in its early history. According to Pelikan:

To validate its existence, the church looked increasingly not to the future, illumined by the Lord’s return, nor to the present, illumined by the Spirit’s extraordinary gifts, but to the past, illumined by the composition of the apostolic canon, the creation of the apostolic creed, and the establishment of the apostolic episcopate. To meet the test of apostolic orthodoxy, a movement or idea had to measure up to these norms.

Pelikan goes on to say that the apostles became a sort of spiritual aristocracy, and the first century a golden age of the Spirit’s activity. The difference between the Spirit’s activity in the days of the apostolic church and the history of the church was not only a difference of degree, but also of kind. The promises of the New Testament on the coming of the Holy Spirit were referred to the Pentecost event, and only through that event via the apostles, to the church. “The promise that the Spirit would lead into all truth, which figured prominently in Montanist doctrine, now meant principally, if not exclusively, that the Spirit would lead the apostles into all truth, as they composed the creed and the books of the New Testament, and the church.” It was upon these three promises that orthodox believers built the foundation of the church. However, Pelikan himself stated that the church has never been altogether without the spontaneous gifts of the Holy Spirit, even where the authority of the apostolic norms has been most incontestable.

The above discussion of Montanism described many parallels to the current debate among believers regarding the continuation or cessation of prophecy. The opposition of Old and New Testament prophets to new prophecy, the de-emphasis of the imminent return of Christ, passive spokesmanship for God in the act of prophecy (from the belief in the direct inspiration of the prophetic word by the Holy Spirit), charges of the possibly demonic source of “new prophecy” are all issues that we encounter in the modern debate of the cessation or continuation of the spiritual gifts. The issues are not new ones, but ones that have surfaced over and over again within the history of the church.

If you have an interest in learning more about Montanism, you can listen to a YouTube lecture and power point presentation, “Montanism for the Modern Church.”