If Not Psychiatry, What Then?

In June of 2021, the World Health Organization published a document, “Guidance on Community Mental Health Services.” The WHO document is seeking to provide quality care and support for person-centered, human rights-based and recovery-oriented mental health care and services worldwide. In a video launch of the event, Sir Norman Lamb said: “Our collective aim must be to end coercive practices, including seclusion and restraint, forced admission and treatment. And we must combat violence, abuse and neglect. This is an urgent imperative for all countries. It’s a global human rights priority.”

Reports from around the world highlight the need to address discrimination and promote human rights in mental health care settings. This includes eliminating the use of coercive practices such as forced admission and forced treatment, as well as manual, physical or chemical restraint and seclusion and tackling the power imbalances that exist between health staff and people using the services. Sector-wide solutions are required not only in low-income countries, but also in middle- and high-income countries.

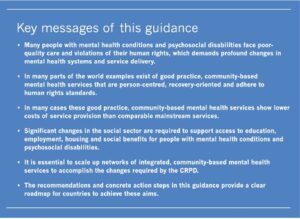

The Executive Summary of the WHO report said global mental health services often face substantial restriction of resources, and operated with outdated legal and regulatory frameworks. There was an overreliance on the biomedical model, where the predominant focus of care was on diagnosis, medication and symptom reduction. Overlooked were the social determinants that impact people’s mental health, hindering progress towards a fuller realization of a human rights-based approach. “As a result, many people with mental health conditions and psychosocial disabilities worldwide are subject to violations of their human rights – including in care services where adequate care and support are lacking.” Key messages of the Guidance said:

According to the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2017, the global median government expenditure on mental health is less than 2% of total government health expenditure. In order to develop quality mental health systems with enough human resources to provide the services and provide adequate support of people’s needs, allocating adequate financial resources is essential. But the problems with mental health provision cannot be dealt with by simply increasing resources. “In fact, in many services across the world, current forms of mental health provision are considered to be part of the problem.”

According to the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2017, the global median government expenditure on mental health is less than 2% of total government health expenditure. In order to develop quality mental health systems with enough human resources to provide the services and provide adequate support of people’s needs, allocating adequate financial resources is essential. But the problems with mental health provision cannot be dealt with by simply increasing resources. “In fact, in many services across the world, current forms of mental health provision are considered to be part of the problem.”

The majority of existing funding is invested in the renovation and expansion of residential psychiatric and social care institutions. This represents over 80% of total government expenditure on mental health for low- and middle-income countries. “Mental health systems based on psychiatric and social care institutions are often associated with social exclusion and a wide range of human rights violations.” While some countries have taken steps towards closing psychiatric and social institutions, this action has not automatically led to dramatic improvements in care. The history of closing psychiatric hospitals in the U.S. illustrates this point.

The predominant focus of care in many contexts continues to be on diagnosis, medication and symptom reduction. Critical social determinants that impact on people’s mental health such as violence, discrimination, poverty, exclusion, isolation, job insecurity or unemployment, lack of access to housing, social safety nets, and health services, are often overlooked or excluded from mental health concepts and practice. This leads to an over-diagnosis of human distress and over-reliance on psychotropic drugs to the detriment of psychosocial interventions – a phenomenon which has been well documented, particularly in high-income countries. It also creates a situation where a person’s mental health is predominantly addressed within health systems, without sufficient interface with the necessary social services and structures to address the abovementioned determinants. As such, this approach therefore is limited in its consideration of a person in the context of their entire life and experiences. In addition, the stigmatizing attitudes and mindsets that exist among the general population, policy makers and others concerning people with psychosocial disabilities and mental health conditions – for example, that they are at risk of harming themselves or others, or that they need medical treatment to keep them safe – also leads to an over-emphasis on biomedical treatment options and a general acceptance of coercive practices such as involuntary admission and treatment or seclusion and restraint.

Reports from countries in all income brackets around the world highlight extensive and wide-ranging human rights violations that exist in mental health care settings. These violations include the use of coercive practices such as forced admission and forced treatment (as with Britney Spears), as well as manual, physical and chemical restraint and seclusion. In many services, people are exposed to poor, inhuman living conditions, neglect, and in some cases, physical emotional and sexual abuse. People with mental health conditions are also excluded from community life and discriminated against in employment, education, housing and social welfare. These violations further marginalize them from society, “denying them the opportunity to live and be included in their own communities on an equal basis with everyone else.”

A fundamental shift within the mental health field is required, in order to end this current situation. This means rethinking policies, laws, systems, services and practices across the different sectors which negatively affect people with mental health conditions and psychosocial disabilities, ensuring that human rights underpin all actions in the field of mental health. In the mental health service context specifically, this means a move towards more balanced, person-centred, holistic, and recovery-oriented practices that consider people in the context of their whole lives, respecting their will and preferences in treatment, implementing alternatives to coercion, and promoting people’s right to participation and community inclusion.

The End of Psychiatry as We Know it?

In Western society, this means challenging the biologically centered, medical model approach to psychiatry. Writing for Psychology Today, John Read noted how global critics of an overly biological approach to understanding and helping distressed people is often dismissed as radical or extremist. Critics of the dominant medical model approach, promoted by the drug companies and biological psychiatry, are often labeled as “anti-psychiatry.” However, Read replied, “We, however, view ourselves as anti-bad and anti-ineffective, unsafe treatments.” He then quoted Steven Sharfstein, then president of the American Psychiatric Association, who said in 2005:

If we are seen as mere pill pushers and employees of the pharmaceutical industry, our credibility as a profession is compromised. As we address these Big Pharma issues, we must examine the fact that as a profession, we have allowed the bio-psycho-social model to become the bio-bio-bio model.

Read also cited Robert Whitaker, who thought the WHO report was a landmark event. There is a global rethinking of how to treat and think about mental health. Whitaker said, “Model programs highlighted in this WHO publication, most of which are of fairly recent origin, tell of real-world initiatives that are springing up everywhere.” Read said it will be become harder for defenders of the medical model to dismiss organizations like the UN or the WHO as extremist, anti-psychiatry radicals. This can be illustrated by looking at how Psychiatric Times launched “Conversations in Critical Psychiatry,” a series of articles and conversations with prominent individuals who are critical of various aspects of psychiatry.

Dr. Awais Aftab, who is a psychiatrist, not only interviews other psychiatrists such as Dr. Ronald Pies, Dr. Giovanni Fava and Dr. Allen Frances, he also talks with individuals from the critical, so-called anti-psychiatry side of the debate, namely Dr. Joanna Moncrieff, Lucy Johnstone and Dr. Sami Timmi. His first interview in 2019 was with Dr. Frances, the Chair of the DSM-IV Task Force and a vocal critic of the DSM-5, over diagnosis and the state of mental health treatment in the U.S. Follow Drs. Frances and Aftab on Twitter to see what they have to say about the current state of psychiatry. One of the concerns for Dr. Fava has been how the psychiatric establishment uses the term “discontinuation syndrome” to describe “antidepressant withdrawal.” In “The Impoverishment of Psychiatric Knowledge,” he said:

If you teach a psychiatric resident that symptoms that occur during tapering cannot be due to withdrawal, he/she is likely to interpret them as signs of relapse and to go back to treatment (exactly what “Big Pharma” likes). In the UK, the NICE guidelines are changing to reflect the potentially malignant outcome with SSRI and SNRI discontinuation. I do not see anything similar happening in the US.

One of the staunchest defenders against so called anti-psychiatry has been Dr. Ronald Pies, professor emeritus of psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University; and Editor in Chief emeritus of Psychiatric Times. Among the many articles Dr. Pies has written over the years defending establishment psychiatry and psychiatric practice are these on Psychiatric Times from the past year: “What Kind of Science is Psychiatry?”, “Do Psychiatrists Treat Diseases?,” and “Why Thomas Szasz Did Not Write The Myth of the Migraine.” He also wrote “Is Depression a Disease?”, about a report from the British Psychological Society whose central argument was that depression is best thought of as an experience rather than a disease; and “Poor DSM-5—So Misunderstood!”, which challenges the claim that the DSM-5 “offers a biomedical framing of people’s experiences and distress and impairment.”

In “The Battle for the Soul of Psychiatry,” Dr. Aftab and Dr. Pies talked about various issues he’s faced over his career. Dr. Pies agreed with Dr. Aftab that they could have done a better job of counteracting “the so-called ‘chemical imbalance’ trope.” Pies wished he had tackled that issue earlier than 2011. He acknowledged the field of psychiatry took a “fairly sharp turn” toward the biological from roughly 1978 to 1998, “which, to a considerable degree, persists to this day.” Dr. Pies thought the movement toward the biological/biochemical was heavily influenced by the pharmaceutical industry.

His hope for the future of psychiatry was to recover its pluralistic core. He said his department at SUNY Upstate Medical University emphasized the integration of psychopharmacology and psychotherapy, and explicitly endorsed “the biopsychosocial approach.” He supported constructive critics of psychiatry, whose aim was to improve the profession’s concepts, methods, ethics, and treatments. He rejected the “anti-psychiatry” critics, saying their rhetoric was clearly aimed at discrediting psychiatry as a medical discipline. This last charge by Pies seems to be true to a degree.

In their book, Psychiatry Under the Influence, Robert Whitaker and Lisa Cosgrove (two of the anti-psychiatry critics) said the time was ripe for a paradigm shift. Many Americans are seeking alternatives to psychiatry’s medication-centered care. Disagreeing with Dr. Pies, they believed psychiatry was facing a legitimacy crisis from a scientific standpoint. Second generation psychiatric drugs are no better than the first, belying the claim psychiatry is progressing in its somatic treatment of psychiatric diseases. “The disease model paradigm embraced by psychiatry in 1980 has clearly failed, which presents society with a challenge: what should we do instead?”