Striving After Wind with NPS

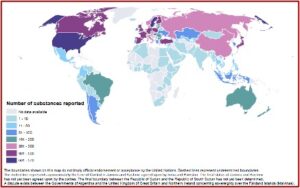

A few years ago, the problem with new psychoactive substances seemed to predict a dire future. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC) launched the Early Warning Advisory on NPS in June of 2013 to address the growing emergence of NPS at the global level. The term “new” can be misleading, as many NPS were first synthesized decades ago, but only recently became recreational drugs. As of December 2021, data reported to the UNDOC Early Warning Advisory 1,124 substances have been reported by governments, laboratories and partner organizations. All told, 134 countries and territories globally have reported one or more NPS.

NPS are not controlled under the International Drug Control conventions, so their legality can vary widely from country to country. By 2021, over 60 countries had implemented legal responses to control NPS. Many countries amended existing legislation, while others used innovative legal instruments. Several countries where a large number of NPS rapidly emerged, adopted controls on entire substance groups of NPS, or introduced analogue legislation that invokes the principle of “chemical similarity” to an already controlled substance explicitly mentioned within the legislation.

The World Drug Report 2021 (Executive Summary, Book 1) indicated these measures helped the number of NPS emerging on the global market to fall from 163 in 2013 to 72 in 2019. But this occurred primarily in high-income countries. “However, the NPS problem has now spread to poorer regions, where control systems may be weaker.” Seizures on synthetic NPS in Africa rose from less than 1 kg in 2015 to 828 kg in 2019. A similar trend was seen in Central and South America, where seizures rose from 60 kg to 320 kg over the same period of time.

Responses that have helped to contain the supply of NPS and reduce negative health consequences can be expanded to lower-income countries, some of which are increasingly vulnerable to the emergence of NPS. Those responses include early warning mechanisms that ensure a continuum of evidence-based measures from early detection to early action, post-seizure inquiries, including the formation of joint investigation teams, and training of emergency health workers on how to address cases of acute NPS intoxication. The expansion of services for people who use drugs and people with drug use disorders to people who use NPS can also help addressing the harm posed by those substances.

The use of NPS is often linked to health problems. Side effects range from seizures to agitation, aggression, acute psychosis and the potential for drug dependence. NPS users have frequently been hospitalized with severe intoxications. Information on long-term adverse effects is still largely unknown, and safety data on toxicity is limited or nonexistent. “Purity and composition of products containing NPS are often not known, which places users at high risk as evidenced by hospital emergency admissions and deaths associated with NPS, often including cases of poly-substance use.”

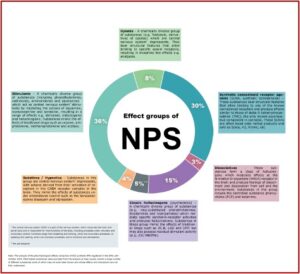

Effect Groups of New Psychoactive Substances

Up to December of 2021, there were six main pharmacological ‘effect’ groups of NPS: stimulants, synthetic opioids, synthetic cannabinoids, dissociatives, classic hallucinogens and sedatives/hypnotics. Stimulants (36%) and synthetic cannabinoids (30%) were the most common, while sedative/hypnotics, mimicking the effects of benzodiazepines (4%) and dissociatives (3%) were the least common. Synthetic opioids accounted for 8% and psychedelics or classic hallucinogens 15% of NPS. See the following graphic presentation of these groups.

Van Hout et al described health and social consequences of recent NPS use among a survey of 3,023 users in six European countries. Socially marginalized respondents (who are also high-risk drug users), were often unemployed, homeless and/or in care. They were the oldest, with an average age of 33.5 years. A substantial proportion of them lived in homeless shelters or hostels (32.3%) or other living arrangements (12.3%), including living on the streets. The education achievement of most marginalized respondents (55.2%) was only up to the equivalent of high school. Among marginalized respondents, 75.7% were unemployed or living on benefits.

The other two groups of those surveyed, nightlife NPS respondents and online respondents, tended to live with relatives or in rented accommodations. They were better educated and significantly less likely to be unemployed or living on benefits (10.8% and 8.1% respectively). Within all three subsamples, a majority of recent NPS users had experienced acute unpleasant side effects. See Table 4 in Van Hout et al.

In terms of reporting of acute side effects, experiences of increased heart rate and palpitation, dizziness, anxiety and horror trips and headaches were reported as most common across all three categories. The proportion who had experienced these effects was substantially larger in the marginalised sample (85.3%), than in the night life and online community samples (58.8 and 51.0%). When looking at the separate side effects, there are significant differences between the three groups in every symptom, with mostly much higher proportions of marginalised users reporting these effects. When comparing night life users and online community users, night life users reported more unpleasant effects, especially head and stomach aches and dizziness. However, in all categories, marginalised users show much higher rates than the two other groups. Increased heart rate or palpitation was the most reported side effect in all three samples.

Benzodiazepine-Type NPS

Benzodiazepines and benzo-type NPS, primarily etizolam, flualprazolam and flubromazolam are often detected in drug overdose cases and can contribute to serious adverse health effects, particularly when used in combination with opioids. “Current NPS threats”, vol. 3 reported that benzo-type NPS were identified in 48% of post-mortem cases as having been the cause of death or contributing to the cause of death.

The analysis presented here reveals that benzodiazepine-type NPS can play an important role in contributing to serious harm, either alone or in combination with other psychoactive substances. Thus, forensic laboratories should ensure that they have appropriate analytical methods available for their detection in case work.

NPS with Opioid-Like Effects

NPS opioids seem to be a fast-growing category of NPS over the past five years. They include a range of fentanyl analogues and research opioids that were developed by the pharmaceutical industry, beginning in the 1960s, as alternatives to morphine for pain management. “Some of these substances were not developed further and were subsequently considered ‘not suitable for human consumption.’” Some of these opioids have been rediscovered. Others have been developed by modifying their chemical structure, which creates a “new” chemical compound and circumvents existing legislation. While they are dissimilar in their chemical structure, the common action of NPS opioids is they act on the mu opioid receptor. The harms associated with NPS opioids other than fentanyls vary considerably.

NPS with opioid-like effects continue to emerge on illicit drug markets, and “Current NPS threats” highlighted three. Isotonitazene, a synthetic opioid has been seen in Europe and North America. Since June of 2019, there were eight incidents of fatalities associated with isotonitazene in the US reported to UNODC. In seven cases it was assessed to be the cause of death. Because of its novelty and opioid-like effects, it could have been misinterpreted as a heroin overdose, masking other cases of fatality.

Kratom, usually involving the concomitant use of other substances, has shown a potential to cause serious harm, including fatalities. Ninety percent of all kratom cases involved the concomitant use of other substances. Since July of 2019, at least 14 cases have been identified where kratom caused (n=7) or contributed (n=7) to a fatality.

Brorphine was first identified in the US recreational drug supply in July of 2020. Its emergence seems to be directly linked to the DEA’s scheduling of isotonitazene. It is commonly found with fentanyl and flualprazolam. “Current NPS threats” said it appears to have a long half-life and high potency when compared to medicinal opioids like hydromorphone. “Despite having structural similarities to fentanyl, brorphine differs in key aspects from fentanyl and falls outside the scope of generic legislation aimed at covering fentanyl analogues.” Between June and November 2020, 120 overdose deaths attributed to brorphine were reported in the US.

Reflecting on the evolving history of NPS, I’m reminded of the book of Ecclesiastes, which says: “Is there a thing of which it is said: ‘See this is new’?” It has been done already and is a vanity—a striving after wind.

What is crooked cannot be made straight, and what is lacking cannot be counted. (Ecclesiastes 1:15)