Tramadol Is not a Safe Opioid

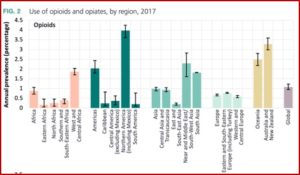

The 2020 World Drug Report said the non-medical use of opioids has always been associated with the most serious health consequences among the various types of drugs. But in the last few years new threats have emerged with regard to the non-medical use of pharmaceutical opioids, leading to alarming rates of dependence and overdose deaths. The problems in North America with fentanyl and its analogues have led to an unprecedented increase in opioid overdose deaths. But in West, Central and North Africa, the Middle East and Asia, another opioid has emerged as a major concern—tramadol.

Tramadol’s potency was said to be comparable to codeine, about 10% the potency of morphine. This led to initial belief that it had a low risk of abuse when it was brought to market in the 1960s by the German pharmaceutical company Grunenthal. However, researchers later found that tramadol releases a far more powerful dose because of how it is metabolized by the liver. An article in The British Medical Journal, “Chronic use of tramadol after acute pain episode” said tramadol undergoes demethylation in the liver to the active metabolite desmatramadol, giving it an opioid effect comparable to morphine.

The BMJ article reported a study by researchers at the Mayo clinic that found patients who received tramadol for the acute treatment of pain had slightly higher rates of long-term opioid use after surgery. The senior author of the study said their finding did not support the idea that tramadol is less habit forming than other opioids. The lead author of the study said: “And while tramadol may still be an acceptable option for some patients, our data suggests we should be as cautious with tramadol as we are with other short-acting opioids.” Tramadol use has been increasing and was the third most prescribed opioid in the study at 4%, after hydrocodone (51%) and oxycodone (38%). “Although all factors related to the safety of a drug must be considered, from the standpoint of opioid dependence, the Drug Enforcement Administration and FDA should consider rescheduling tramadol to a level that better reflects its risks of prolonged use.”

While many countries in West, Central and North Africa report the non-medical use of tramadol as one of the main threats in drug use, quantitative information on the actual size of the population using tramadol non-medically was not available in most countries, according to the 2020 World Drug Report. However, treatment data in West African countries revealed tramadol to be the main drug of concern for people with drug use disorders. “Tramadol ranks highly among the substances for which people were treated in West Africa in the period 2014–2017.” In North Africa, Egypt reported tramadol is the main opioid used non-medically. In drug treatment, tramadol was also the primary drug, accounting for 68% of all people treated for drug use disorders in 2017. In the Sudan, the increasing non-medical use of pharmaceutical drugs among young people includes: tramadol, benzodiazepines, cough syrups and antihistamines, trihexyphenidyl (an antiparkinsonian agent), anticonvulsants, pregabalin and gabapentin.

In Iran, a recent study estimated that or 200,000 people aged 15-49 in urban centers had misused tramadol, most of whom were young people. The past 12-month of non-medical use of tramadol in the general population was 4.9 percent among men and .5 percent among women. In recent years, tramadol intoxication and fatal overdose, especially among young people with a history of substance use disorder and psychiatric comorbidity, has been a major cause of emergency department admissions. Among these cases, tramadol has been misused with other substances, especially benzodiazepines. “Tramadol was also found to be the cause of death in around 6 per cent of the total drug overdose death cases in the Islamic Republic of Iran reported in different studies from 2006 to 2017.”

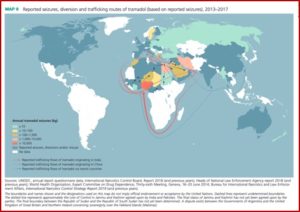

AP News reported in “How tramadol, touted as safer opioid, became 3rd world peril,” that mass abuse of tramadol spans continents from India to Africa and the Middle East, creating international havoc. Some experts blame a loophole in narcotics regulation and a miscalculation of the drug’s danger. It was touted as a way to relieve pain with little risk of abuse. Unburdened by international controls that track most dangerous drugs, tramadol flows freely around the world. “But abuse is now so rampant, that some countries are asking international authorities to intervene.”

Grunenthal is campaigning to keep the status quo with tramadol regulation, arguing that typically it is illicit counterfeit pills causing problems. International regulations make narcotics difficult to get in countries with disorganized health systems. Adding tramadol to the list, the company said, would deprive suffering patients access to any opioid at all. The secretary of the World Health Organization’s committee recommending how drugs should be regulated said this is a huge public health dilemma. “It’s a really very complicated balance to strike.” Tramadol is available in war zones and impoverished nations because it is unregulated—the same exact reason it is widely abused.

Tramadol has not been as deadly as other opioids, and the crisis isn’t killing with the ferocity of America’s struggle with the drugs. Still, individual governments from the U.S. to Egypt to Ukraine have realized the drug’s dangers are greater than was believed and have worked to rein in the tramadol trade. The north Indian state of Punjab, the center of India’s opioid epidemic, was the latest to crack down. The pills were everywhere, as legitimate medication sold in pharmacies, but also illicit counterfeits hawked by street vendors.

Authorities in Punjab seized hundreds of thousands of tablets, banned most pharmacy sales and shut down pill factories, pushing the price from 35 cents for a 10-pack to $14. When the government opened a network of treatment centers, fearful those who had become addicted would resort to heroin out of desperation, hordes of people rushed in seeking help. Tramadol had become as essential as food. A 30-year-old auto shop welder said, “Like if you don’t eat, you start to feel hungry. Similar is the case with not taking it.”

In 2016, Jeffery Bawa, an officer with the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, traveled to Mali in West Africa, one of the world’s poorest countries, which also struggles with civil war and terrorism. When he asked people what their most pressing concern was most said tramadol, not hunger or violence. At a United Nations meeting on tramadol trafficking, Nigerian officials said the number of people living with addiction is far higher now then the number with AIDS or HIV. In Cameroon, scientists thought they had discovered a natural version of tramadol in tree roots. “But it was not natural at all: Farmers bought pills and fed them to their cattle to ward off the effects of debilitating heat. Their waste contaminated the soil, and the chemical seeped into the trees.”

Police began finding tramadol pills on terrorists. It seems they now traffic tramadol to fund their networks and use it to bolster their own violent behavior. Most of the supply was coming from India, where pill factories produced counterfeits and shipped them in bulk around the world, “in doses far exceeding medical limits.” In 2017, law enforcement reported confiscating $75 million worth of tramadol from India on route to the Islamic State. Another 600,000 tablets headed for Boko Haram were intercepted. Three million more tramadol tablets were found in a pickup truck in Niger, in boxes disguised with U.N. logos.

Grunenthal has persisted with its campaign to keep tramadol unregulated. It funded surveys that found regulation would impede pain treatment and even paid consultants to travel to the WHO to make their case that tramadol is safer than other opioids. But that could change. Referring to the above-described Mayo Clinic study, AP News noted the researchers were surprised when they found their data indicated patients prescribed tramadol were just as likely to move on to long-term use as other opioids. The lead researcher of the Mayo study said: “There is no safe opioid. Tramadol is not a safe alternative. It’s a mistake that we didn’t figure it out sooner. It’s unfortunate that it took us this long.”