A Coming Opioid Storm?

When Rahul Gupta was sworn in as the Director of the Office of National Drug Policy (ONDCP) on November 18, 2021, he said on Twitter that the overdose epidemic would be his top priority. He is the first physician to lead the ONDCP. President Biden made it clear to him that addressing the overdose epidemic was an urgent priority. “As director, I will diligently work to advance high-quality, data-driven strategies to make our communities healthier and safer.” Tellingly, the day before Gupta was sworn in, the CDC reported on November 17th that there were an estimated 100,306 drug overdose deaths in the U.S. during the 12-month period ending in April of 2021, an increase of 28.5% from the same time period the year before.

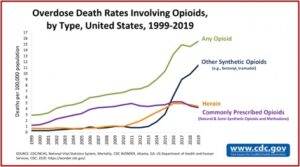

Overdose deaths from opioids increased to 75,673 in the year prior to April 2021, an increase of 35% from the same time period the year before. Nearly 500,000 people died from overdoses involving any opioid from 1999-2019. The CDC said this took place in three distinct waves, with commonly prescription opioids (1990s), heroin (2010) and synthetic opioids (2013). See the graph below, which shows the three categories as well as opioids overall.

The Stanford-Lancet Commission was formed in response to the rising opioid-related morbidity and mortality rates in the USA and Canada over the past 25 years. An article by Humphreys et al in The Lancet in February of 2022, “Responding to the opioid crisis in North America,” noted that in the past 25 years, more people died of overdoses in the USA and Canada than World War 1 and World War 2 combined. Following the above-noted waves, the article made the following observations.

Humphreys et al said the approval of Purdue Pharma’s opioid medication OxyContin in 1995 marked the beginning of the first wave. Purdue fraudulently marketed it as less addictive than other opioids and thus more acceptable for a broad range of indications at high doses. See “Giving an Opioid Devil Its Due,” “The Tale of the OxyContin Lie,” and “Doublespeak in the Opioid Crisis, Part 2” for more on Purdue Pharma and OxyContin.

Backed by the most aggressive marketing campaign in the history of the pharmaceutical industry, OxyContin became the best known of a number of opioid medications (both extended-release and immediate-release formulations) whose prescription rate exploded in the USA and Canada.

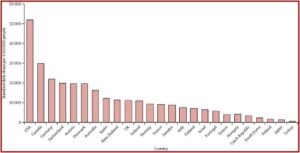

There was a departure from decades of medical practice where opioids were used mainly for cancer, surgery and palliative care (people living with a serious illness like cancer). US and Canadian medical practitioners expanded opioid prescribing to include a broad range of non-cancer pain conditions that included lower back pain, headaches and sprained ankles. Per-person opioid prescribing roughly quadrupled between 1999 and 2011. There were 275 million opioid prescriptions written—approximately equal to the population of the two nations. The following graph shows UN data on international per-person consumption of opioids in 2010-12.

The political and cultural environment at the time the crisis emerged was not conducive to an early response; indeed, complacency allowed it to worsen. To attain respectability, trust, and influence throughout the world, opioid manufacturers strategically donated a small share of their profits to prominent institutions, including hospitals, medical and dental schools, universities, museums, art galleries, and sporting events. These donations secured goodwill and increased the credibility of the industry’s message that it was a selfless healer, pushing back against cruel anti-opioid prejudices.

The second wave began around 2010, as drug traffickers realized individuals addicted to prescription opioids were an untapped potential market for heroin. People were drawn in by the comparatively lower price of heroin. Before controls on prescribing were introduced, an analysis of national data suggested that 79.5% of Americans using heroin started with prescription opioids. When efforts began to stop the increase in prescriptions and reduce diversion of prescription opioids, addicted people began turning to heroin more rapidly than they otherwise might have.

The third wave of the opioid crisis began around 2014, as illicit drug producers began adding extraordinarily powerful synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, to counterfeit pharmaceutical pills, heroin, and stimulants. This wave brought unprecedented lethality in addition to—rather than instead of—the previous waves, both of which continue today. Large numbers of US and Canadian people are still becoming addicted to prescription opioids each year, and most of those who die from heroin and fentanyl overdoses are previous or current users of prescription opioids.

An anonymous editorial in The Lancet accompanied the report of the Stanford-Lancet Commission, Managing the opioid crisis in North America and beyond.” It said the COVID-19 pandemic may have contributed to the number of overdose deaths by disrupting treatment programs and access to medications like naloxone, as well as disrupting support networks. The Commission called for characterizing opioid use disorder (OUD) as a chronic condition, requiring “innovation in treatment of OUD and in the treatment of pain. However, this innovation “must be met with reinforced regulation.”

A Mental Elf article commenting on the Stanford-Lancet Report, said it was an important and authoritative summary of the development of the opioid crisis in North America. It was called an invaluable resource for anyone interested in the problems associated with opioids. But the author, Ron Poole, thought it has a number of weaknesses. He said in his opinion, “at the heart of the international opioid problem is a false belief that pain can be eliminated pharmaceutically.” If we are to move forward, we need to embrace a rehabilitation approach to chronic pain “where opioids play a small and specific role,” rather than continuing to search for an “analgesic magic bullet.”

The pain-elimination myth is not soley the creation of the pharmaceutical industry; it has deep-seated roots in medical socio-cultural beliefs.”In the UK, gabapentinoids are frequently used alongside heroin, and the combination is a potent cause of respiratory depression and death. Gabapentinoids have a limited role in pain management, but they are widely prescribed. They are dependency forming in much the same way as benzodiazepines. Gabapentinoids are not mentioned in the Report.

Poole is right to point to these weaknesses with the Stanford-Lancet Report, especially the failure to mention that gabapentin, which is the sixth-most prescribed medication in the U.S. It has an addictive potential, but is not yet a scheduled substance by the DEA. Other researchers have referred to concomitant use of gabapentinoids and heroin as an emerging public health problem. See “The Truth About Gabapentin.”

Hopefully, we will have time to implement the recommendations in the Stanford-Lancet Report. Humphreys et al said it took more than a generation of mistakes to create the opioid crisis in North America and might take a generation of wiser policies to resolve it. Let’s hope the three “waves” of the opioid crisis, illustrated in the above CDC graph, aren’t signaling a coming storm surge of the opioid epidemic before that time.