Freud’s Nanny

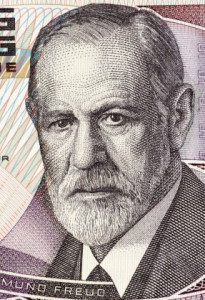

Sigmund Freud is widely known to have been an atheist or agnostic. Ernest Jones, his biographer, friend and close colleague said he went through life from beginning to end as an atheist: “One who saw no reason for believing in the existence of any supernatural Being and who felt no need for such a belief.” His daughter Anna, herself a psychoanalyst, said her father was a “lifelong agnostic.” He regularly described religion as “a universal, obsessional neurosis.” In The Future of an Illusion (1927), he said religious doctrines were also illusions—wish fulfillments of the oldest, strongest and most urgent desires of mankind. But what would you think if, as a child, Sigmund Freud had been taken regularly to Catholic Mass and quite possibly had been secretly baptized?

Paul Vitz supported these claims in his book: Sigmund Freud’s Christian Unconscious. He said Freud had “a strong, life-long, positive identification with and attraction to Christianity.” According to Vitz, this was offset by a concurrent and unconscious hostility to Christianity, reflected in his preoccupation with the Devil, Hell, and the Anti-Christ. He thought this substantial Christian and anti-Christian part of Freud provided an understanding of his adult ambivalence towards religion; and should suggest a re-evaluation of Freud’s psychology of religion.

Freud was born on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg Moravia—a town now part of the Czech Republic. At the time, Moravia was a predominantly Catholic region, with a particular devotion to the Virgin Mary. The main church in Freiberg was called “The Nativity of Our Lady.” The town had a population of about 4500, over 90% of whom were Roman Catholic. About 3% of the city were Jewish. Freud lived there with his family until he was three years old. After a brief time in Leipzig, the family moved to Vienna, where Freud lived all but the last fifteen months of his life. Vienna was also predominantly Roman Catholic. “As a result, Freud spent almost his entire life as a Jew in a society dominated by Roman Catholic culture.”

Resi (short for Theresa) Wettik was in the employ of the Freud family by June of 1857 at the latest. Freud himself wrote that he was in her charge from some time “during early infancy.” Family matters support the likelihood that Resi assumed a major maternal role with young Sigmund from an early date. Sigmund had a younger brother, Julius, who was born when Freud was fifteen months old (August of 1857). Julius was sickly and died on April 15, 1858, just before Sigmund was two. Seven and a half months later, his mother gave birth to his sister, Anna.

So when Freud was between the ages of one and three, his mother Amalia went through two pregnancies and births, and was caring for the sickly Julius, who died when he was eight months old. Vitz observed that Freud must have found his mother relatively unavailable from around the age of one until he was close to three years old. “There is, then, every reason to believe that the nanny filled the maternal vacuum during this important period, and that Freud experienced her as a second mother—or even … as his primary mother.”

Amalia Freud was 21 at the time she gave birth to Sigmund. During the first 32 months of his life, she was pregnant for a total of 18 months. Since during pregnancy, a mother’s milk supply diminishes, there is a strong possibility that she did not breast-feed, or at least did not fully breast-feed very long after her children’s births. Vitz explained that it is rare for a woman to get pregnant while nursing her baby regularly the first six months after giving birth. “In any case, it is unlikely that Sigmund was nursed by his mother for more than a brief period.”

While not definitive, this and others evidence suggests that Resi was also a wet nurse to young Sigmund. A biographer of Freud’s indicated the Freud women frequently worked together in a “garment district” warehouse, while the children were cared for by a maid, presumably Resi. “If so, Sigmund would have been almost exclusively with the nanny for many weeks during his earliest years.” Freud himself seems to have acknowledged this in letters he wrote to his friend, Wilhelm Fliess. This was during the time he was in the midst of his own self-analysis when he was in his forties.

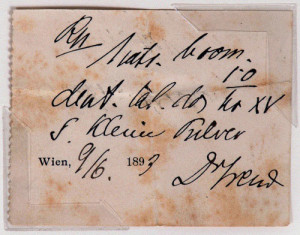

Vitz quoted from a letter Freud wrote to Fliess on October 3, 1897. He said there had been something interesting things with his self-analysis over the previous four days. He referred to his nanny as the “prime originator” figure of his dream, meaning she was a parent (an originator) to him. “The ‘prime originator’ was an ugly, elderly, but clever woman, who told me a great deal about God Almighty and hell and who instilled in me a high opinion of my own capacities.” Resi may have only been in her later thirties or early forties. “Elderly” here could then be the perspective of Freud as a child in the dream or his mother, who was herself only in her early twenties at the time.

I have not yet grasped anything at all of the scenes themselves, which lie at the bottom of the story. If they come [to light] and I succeed in resolving my own hysteria, then I shall be grateful to the memory of the old woman who provided me at such an early age with the means for living and going on living.

In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud wrote that he had a vague memory of his nanny. He added that: “it is reasonable to suppose that the child [Freud] loved the old woman.” Vitz commented that Freud didn’t make such claims about the early importance of his own mother. “Indeed, this lack of evidence further supports the present view that the nanny was the primary mother.” In an October 15, 1897 letter to Fliess, Freud said he’d asked his mother if she remembered his nurse. “’Of course,’ she said, ‘an elderly person, very clever, she was always carrying you off to some church; when you returned home you preached and told us all about God Almighty.’”

Paul Vitz said while it would have been unusual in most Christian homes at the time to attend Mass several times a week, it would not have been unusual for a pious woman of the time to do so. However, for it to occur “within a Jewish home would have been quite striking.” There was no synagogue in Freiburg, so Freud would not have had the opportunity to be exposed to any Jewish religious experience in these early years. Nor is there any evidence that the Freuds celebrated the Jewish holidays, or kept the Jewish dietary laws while living in Freiberg. Additionally, “There is no reason to believe that Freud’s mother gave him religious instruction; she is known to have been uninterested in religion.”

In any case, the nanny, this functional mother, this primitive Czech woman who was the “primary originator” of Freud, was his first instructor in religion. These first lessons were of a simple, no doubt often simple-minded, Catholic Christianity.

Vitz said that given the likelihood of a close relationship between the nanny and young Sigmund, there is a distinct possibility that she may have secretly baptized him. With the death of his sickly, infant brother, the nanny may have even baptized Julius. Or his death without baptism would have been a disturbing tragedy to her. Either possibility would arouse her fears and concern for Sigmund. “Such a possible covert baptism, in church or otherwise, may have had a lasting effect on Freud’s memory; if the nanny had talked about the meaning of baptism, it would have left permanent traces.”

Freud’s mother related a story that his nanny was abruptly dismissed by the Freuds, supposedly because she was discovered to have been stealing. Reportedly, Amalia told her son this happened while she was still bed ridden after the birth of Anna in December of 1858. Vitz questioned both the timing of the dismissal, suggesting it occurred in late May or early June of 1859, and the circumstances of the nanny’s dismissal. He noted Amalia’s recollection of the event was almost forty years after it occurred. Also the alleged circumstances were odd. The nanny was said by Freud’s mother to have been found with coins and toys that had been given to Sigmund. Why, asked Paul Vitz would such a clever woman keep the toys with the coins and not hide them in a safe place?

All this is most odd, especially given the extreme likelihood that Freud’s mother must have looked on the nanny with increasing jealousy and dismay. Here was this peasant woman who was in many ways taking over the role of a mother in the life of her lively and attractive first-born son. Not only was the nanny coming to be extremely important to her son’s affections, but she was also taking him to church and instructing him in Christianity. Amalia Freud was never very serious about her own Judiasm; still, there is certainly no reason to think she was benevolently disposed towards Christianity. Possibly, her young son’s early training in Christianity roused real concern. If so, this was a reason why the Freuds, in particular Amalia, would have wished to get rid of the nanny.

So soon after Sigmund turned three, he was suddenly separated from his nanny; his motherly “prime originator.” Again in the letter to Fliess on October 15, 1897, Freud wrote that if he was suddenly parted from her, “it must be possible to demonstrate the impression this made on me.” He then described to Fliess what he believed to be a childhood memory that had emerged repeatedly into his conscious memory over the years (without understanding it). The memory was of a time when he couldn’t find his mother, and he was crying uncontrollably for her. “When I missed my mother, I was afraid she had vanished from me, just as the old woman had a short time before.”

The significance of these events is striking when they are seen in the light of Freudian theory. Ernest Jones said in his biography of Freud that he taught: “The essential foundations of character are laid down by the age of three and that later event can modify, but not alter the traits then established.” Paul Vitz observed that you don’t have to believe this theory of character is universally true “to accept that it was most certainly true of its originator.”

Quotes used in this article are from Sigmund Freud’s Christian Unconscious, by Paul C. Vitz, and The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess 1887-1904, translated and edited by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson.