The Psychedelic Pendulum and Psychiatry, Part 2

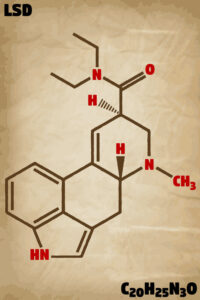

On October 12, 1955 psychiatrist Sidney Cohen took LSD for the first time. Expecting to feel catatonic or paranoid because LSD was then thought to produce a temporary psychosis, he instead felt an elevated peacefulness, as if the problems and worries of everyday life had vanished. “I seemed to have finally arrived at the contemplation of eternal truth.” He immediately began his own LSD experiments, even exploring whether it could be helpful in facilitating psychotherapy, curing alcoholism and enhancing creativity. But on July of 1962 in The Journal of The American Medical Association, he warned of the dangers of suicide, prolonged psychotic reactions, and said: “Misuse of the drug alone or in combination with other agents has been encountered.”

The history of psychedelics seems have followed this pendulum swing from hope and promise, to disappointment and warnings, and then back again to hope and promise. In Part 1 of this article, we looked at the current promise of psychedelic therapy and treatment and mentioned its use to supposedly enhance creativity. Here we’ll take a closer look at the present-day concerns and reservations with the proposed use of psychedelics as therapeutic tools. Tellingly, they haven’t change much since Cohen co-authored “Complications Associated with Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD-25).”

In “Psychedelics—The New Psychiatric Craze,” Joanna Moncrieff acknowledged the “increasingly fashionable” interest in psychedelics as a medical treatment, but wondered if they weren’t just “a powerful form of snake oil.” She noted the ever-lengthening list of problems they were recommended to treat, which included PTSD, depression, anxiety, addiction, chronic pain and distress associated with having a terminal illness. The rationale behind the trend was said to be confusing and contradictory.

On the one hand, psychedelics are promoted as assisting the process of psychotherapy through the insights that the ‘trip’ or drug-induced experience can generate – on the other they are claimed to represent a targeted medical treatment for various disorders, through correcting underlying brain deficiencies.

Increasingly, the use of these drugs is portrayed as if they work by targeting underlying dysfunctional brain processes (i.e., resetting brain processes by acting on 5-HT2A receptors). Moncrieff said claims by David Nutt, a psychopharmacologist and psychedelic researcher that psychedelics “turn off parts of the brain that relate to depression” and reset the brain’s thinking processes by their actions on the 5-HT2A receptors were “pure speculation.” She made the same judgment on a John Hopkins website that said researchers hoped to “create precision medicine treatments tailored to the specific needs of individual patients.” The charity, Mind Medicine Australia’s claim that psychedelic treatments were curative and only required 2-3 dosed sessions, that they were “antibiotics for the mind”, Moncrieff thought was a sales pitch for an expensive therapy.

In reality, psychedelics do not produce the miracle cures people are led to expect, as experience with ketamine confirms. Some people may feel a little better after a treatment, and then the effect wears off and they come for another one and another one, and get established on long-term treatment just as people do on antidepressants.

Official research also over-plays the drug’s benefits. A study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, “Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression,” found no significant difference between groups in their primary outcome. The study’s discussion then pointed out that secondary outcomes had small differences, but did not consider the placebo effect of participants having a drug-induced experience. The participants were also not typical of those with depression, consisting of mainly well-educated men, almost a third of whom had tried psychedelics before. The study’s researchers said:

The patients in the trial were not from diverse ethnic or socioeconomic backgrounds. Strategies to improve recruitment of more diverse study populations are needed in studies of psilocybin for depression. Also, average symptom severity scores at baseline were in the range for moderate depression, thus limiting extrapolations to patients with severe depressive symptoms or treatment-resistant depression.

The current craze for psychedelics means adverse effects are being minimized, according to Moncrieff. Whether or not people find the effects of psychedelics enlightening or not depends on how the drug-induced experience is interpreted. This highlights the importance of staff as support people while clients are under the influence. Yet she worried that when, and if, psychedelics obtain a medical license, psychotherapy would be dropped or minimized. “The tendency of all psychedelic treatment will be towards the provisions of the drug in the cheapest possible way, which means the minimum of supervision and therapy.”

In “When Drugs of Abuse Become Psychiatric Medications,” Sara and Jack Gorman noted that some commentators have been suggesting we’re on the cusp of a new era in psychopharmacology with the potential of ketamine, MDMA and psilocybin as psychiatric treatments for depression, PTSD and other disorders. They noted how we have information about the biological mechanisms of action for all three of them. Ketamine works mainly through interaction with the brain’s glutamate neurotransmission system. MDMD and psilocybin enhance the brain’s serotonin receptors—the same system affected by SSRI antidepressants.

Unfortunately, however, we still have no firm idea if derangements in any of these neurotransmitter systems are actually the cause of any mood or anxiety disorder. There are many theories linking abnormal glutamate neurotransmission to depression, for example, and some solid data from animal studies suggesting such a link, but no definitive proof that any abnormality in glutamate neurotransmission is part of depression yet exists. We cannot say that any of these drugs work by remediating a known abnormality in the brains of people with psychiatric illnesses any more than we can say that about any of the traditional psychiatric medications.

One final issue is that regardless of the fact that currently approved medications for depression and PTSD are only partially effective for many patients, they are not usually abused or addictive. Yet ketamine, psilocybin and MDMA have long histories as recreational street drugs that can be addictive for some people. In the clinical trials done to date adverse side effects have been minimal, and with the doses and manner in which they are given, addiction is unlikely. Moreover, there are widely used, FDA-approved, psychiatric drugs with known histories of misuse—benzodiazepines and ADHD medications.

Then the Gormans asked a telling question: Is psychiatry following solid science, or going in the direction of approving the use of mind-altering street drugs as medications—and I’d add—because they have no other potential medications on the horizon?

In the journal, JAMA Psychiatry, Joshua Phelps and two others expressed concerns with the growth of industry-sponsored drug development and the assessment of psychedelic drug effectiveness. They noted the market for psychedelic substances was projected to grow from $2 billion in 2020 to $10.75 billion by 2027, “a growth rate that may even outpace the legal US cannabis market.” They said the interest in psychedelic medicine seems to hope that psychedelics will be the next blockbuster class of medicines and has led to efforts to decriminalize psychedelics at the local level, as with Oregon (see Part 1) and other locations. Their concern is that these regulatory changes will adversely affect the quality and rigor of biomedical research with psychedelics.

Although popular excitement, policy momentum, and financial investment in psychedelics continue to increase, it is imperative that research maintains scientific rigor and dispassion to outcomes in the pursuit of improved therapeutics and new insights into the mind, brain, and consciousness that this class of molecules may well afford in the coming years. The presence of large-scale, newly established public companies as an unprecedented category of stakeholder may help to further understanding of these molecules and their possible clinical applications, but these firms also have a unique set of self-interests that must be understood and considered. Research enabled by these firms must still meet the same rigorous standards that are expected elsewhere, even if breakthrough status is warranted.

Then there is another concern described by Will Hall on “Ending the Silence Around Psychedelic Therapy Abuse.” He made his decision to write about therapy abuse when he read Michael Pollan’s best-selling book on psychedelics, How to Change Your Mind. Hill thought Pollan was overly enthusiastic and largely uncritical. “All the new hype about miracle psychiatric treatments and the next wave of cures for mental disorders leaves out the risk of therapy abuse.”

He said from his perspective, as far as drugs go, psychedelics were relatively safe—safer than benzodiazepines or SSRIs. He even acknowledged that reported healings from emotional pain with psychedelics did happen. By raising an alarm about therapy abuse he said he wasn’t exaggerating the dangers of psychedelics, rather: “I’m calling for more honesty about the implications of putting psychedelics in the hands of therapists.”

He noted the inherently imbalanced power relationship of therapist and client, where there is already the potential danger of authority being misused. The therapist has too much influence over a client, and the consequences for clients are too severe to see each side as equal, according to Hall. “And so we protect clients from therapists in the same way we protect children from adults, especially from the most exploitive and extreme violation of therapist trust, sex with clients.” The risks are magnified when you add psychedelics.

Drugs affect judgment, drugs can enhance idealization, drugs can promote risk taking, drugs can lower defenses, drugs can amplify suggestibility, drugs can lead to dissociation… all drugs. Imagine if you heard therapists were giving their clients alcohol to get them talkative, lines of cocaine to get them confident, or cannabis to get them relaxed? You would easily recognize that even if some clients do benefit, the client is also put into a heightened and more easily exploited state. Despite their many unique and often positive qualities, this is still true of psychedelics. And the influence is magnified when the therapist is supplier of and expert about the drug, when the drug has a taboo cultural aura of esoteric healing powers, the media are hyping miracle cures, and scientific experts are waving their hands and calling it “medical treatment.” Add that psychedelic therapists are typically also themselves users of and true believers in these substances. The dangers are obvious.

Psychedelics present some of the same risks as any drugs. Hall said we need to name those risks, and be especially vigilant about them. Otherwise, even though some people will be helped, others will be harmed. “And as the history of psychedelic therapy abuse shows, they already have.” Hall then gave specific historical examples and details from past abuse as well as his own personal experiences.

He wasn’t alone in pointing to this safety concern with psychedelic therapy. In her article on Oregon’s experiment with legalizing psychedelics for STAT, Olivia Goldhill noted that sexual abuse has historically been a problem with psychedelic therapy. “All the usual power imbalances of patients and therapists are exacerbated in a setting where drugs can create feelings of sexual arousal.”

Hall also pointed out that with psychedelics or any other drug, “it’s called getting high for a reason—we lose our feet on the ground.” Gaining a new perspective can be illuminating, but avoidance could come instead of insight. Psychedelics also increase suggestibility, a tendency to accept the beliefs of others illustrated in hypnotic trance states and situations where there is social pressure for conformity. Psychedelics can make some people more dependent on outside influence and more reluctant to consider they may have misjudged their safety when using the drugs.

There is more Will Hall has to say about the potential for therapy abuse with psychedelics, but what we’ve reviewed lays out the concerns. I don’t agree entirely with what seems to me to be a “laissez faire” approach to people who want to use psychedelics for healing or illumination. I’d say there is as much of concern with their use as with benzodiazepines or SSRIs. And given the pendulum swing evident in the history of psychedelics as therapeutic agents, there is a swing back to disappointments and concerns ahead. As Hall astutely said,

All medical treatment outcomes are driven in part by expectation and placebo: eventually the hype around new psychiatric products wears off, and then we are on to the next marketing wave—with iatrogenic harm to patients left in the wake.

STAT said that Washington, New York, Colorado and California are all considering some form of legalizing psychedelics. Other states are enacting decriminalization measures. If Oregon-style legislation spreads to other states, the potential market for legalization will get bigger. Field Trip, a company with a series of clinics used for ketamine therapy plans to set up clinics in Oregon. “Oregon is just the first step. But there’s a big wave coming almost certainly.”