Don’t Roll the Dice with MDMA, Part 2

The psychedelics industry is booming, as companies plan out their patent strategies in order to stake out their future share of the market. In the early days of the industry, nonprofits like MAPS and smalltime startups dominated the psychedelics space. Then the FDA granted breakthrough status to MAPS for MDMA-assisted therapy to treat PTSD in 2017. And in 2018 psilocybin-assisted therapy was approved as a breakthrough therapy for treatment-resistant depression. According to Insider, venture capitalists have now invested $139.8 million into startup psychedelic companies in a few short years.

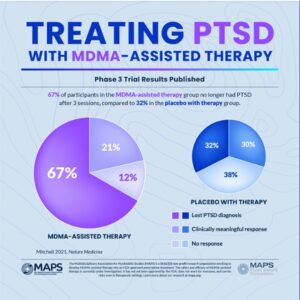

The Hill noted California was on its way to be the third state to decriminalize psychedelics after its Assembly passed Senate Bill 58 by a 42-11 vote. In addition to decriminalizing personal possession and cultivation, the bill would allow “community-based healing” practices to promote the therapeutic use of psychedelics. Interestingly, the specified substances included psilocybin, psilocin, dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and mescaline, but did not mention MDMA. However, ecstasy or MDMA has been progressively moving through the FDA’s clinical trial gauntlet for approval in MDMA-assisted therapy and MAPS recently published the results of its second Phase 3 clinical trial.

MAPS, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, has been advocating for MDMA-assisted therapy to treat PTSD since 1986. In 1985 the DEA classified MDMA as a Schedule I drug, meaning the agency thought it to have no medical use and a high potential for abuse. Rick Doblin, the founder of MAPS said, “The big tragedy to point out is that it was pretty clear in the late 1970s and early 1980s that MDMA had incredible therapeutic potential.” But there is more to know about the history of MDMA and Rick Doblin, who chose PTSD as the disorder to target in his quest to end the government ban on psychedelics.

Doblin said MAPS wanted to help a population that would automatically win public sympathy. “No one’s going to argue against the need to help them [veterans].” When the DEA moved to criminalize MDMA in 1984, Doblin created MAPS and sued the agency, but failed to stop the DEA from permanently classifying it as a Schedule I controlled substance. He realized then psychedelics were seen as too fringe to win public support and decided that both he and the issue needed to go mainstream. So, he applied to the public policy program at Harvard, shaved off his mustache, cut his hair and began to dress more conventionally.

“I used to laugh about how simple it was,” he said. “You put on a suit, and suddenly everyone thinks you’re fine.” Doblin’s dream is to see psychedelic treatment centers in every city, but not simply to treat PTSD. These centers would be where people could go for spiritual experiences, enhanced couples therapy and personal growth. He believes psychedelics can even help homelessness, global warming and world peace: “These drugs are a tool that can make people more compassionate, tolerant, more connected with other humans and the planet itself.”

But this kind of rhetoric makes others nervous. A psychology professor at Swansea University in Wales thinks MDMA’s a dangerous substance. He’s worried FDA approval for the treatment of PTSD will lead many in the public to believe MDMA is safe for recreational use, despite its problematic side effects. See “Give MDMA a Chance?” and “MDMA-Not!” for more information on the history of MAPS and concerns with adverse side effects with MDMA.

Nevertheless, MAPS plans to submit a new drug application (NDA) for MDMA-assisted therapy to the FDA by the end of the year, which brings us to the question posed towards the end of Part 1 of this article: Should the FDA approve MDMA-assisted therapy?

The New York Times described the second Phase 3 clinical trial for MDMA-assisted therapy in “MDMA Therapy [was] Inches Closer to Approval” and said it seemed to be effective in reducing symptoms of PTSD. After giving a brief history of MAPS and Doblin’s efforts towards FDA approval of MDMA-assisted therapy, they gave a summary of MAPP2, the second Phase 3 clinical trial: “MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD,” published in Nature Medicine. The findings were similar to the results of MAPP1, the first Phase 3 study of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD. See Part 1 for a discussion of those findings.

As in previous studies of MDMA-assisted therapy, the treatment was generally well-tolerated, according to the data presented about adverse events. Common side effects, primarily for those in the MDMA group, included muscle tightness, nausea, decreased appetite and sweating.

Two participants in the MDMA group and one in the placebo group experienced serious suicidal ideation during the study, but no suicide attempts were reported.

Allen Frances, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at Duke University and the chair of the DSM-IV, didn’t think the study’s results would meet the FDA’s criteria. He said the benefits in the active group were not much greater than the benefits in the placebo group. The cost of the treatment process would also put it out of the reach of many, if not most, potential patients. “MDMA treatment would add huge costs to the treatment system while providing only a small, specific benefit — and thus result in a massive misallocation of already very scarce resources.”

There is the cost of training therapists for psychedelic-assisted therapy as part of that expense. MAPS already oversees its own therapist education program. But the standards and requirements from the FDA are still not specified for MDMA-assisted therapy. “Drug-assisted therapy hasn’t been approved before, so there’s not a lot of precedent.” Then there is the variability of the price for assisted therapy. MAPS “will not manage how much the therapy component will cost.”

In a Nature news article, “Psychedelic drug MDMA moves closer to US approval,” Eric Turner, a psychiatrist at Oregon Health & Science University (and a former reviewer of psych drugs for the FDA), said while the reported difference between the MDMA and placebo groups was impressive, he doubted it was as big as it seems because it wasn’t a blinded study. “Around 94% of people who received the drug and 75% of those who didn’t correctly guessed which group they were in.” He added that even if MDMA was a safe substance, the study didn’t meet the FDA’s usual criteria for a well-controlled study. Jennifer Mitchell, the lead author for “MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD,” worried about people trying MDMA on their own, where it could be harmful for those with heart conditions or with a family history of schizophrenia, which could be triggered by the drug.

I’ve been following the MAPS progress with MDMA-assisted therapy since 2016. And I’ve also wondered about the associated proliferation of psychedelic start-ups in “Psychedelics Are Not a Magic Bullet.” With the examination of the rhetoric and published spin on the two studies of the clinical trials for MDMA-assisted therapy, I think it almost appears to be a “con job” of rhetoric instead of the steady, progressive march towards the approval of a novel treatment for PTSD. And it seems I am not alone.

Psychologist James C. Coyne was critical of what he saw as a well-orchestrated publicity campaign by the funders of the MDMA research done by MAPS in “The MDMA-Assisted Therapy for PTSD Study: What You’ll Get Wrong.” He focused his critique initially on an older New York Times article, which he accused of “shilling for the promoters of psychedelics.” He likened the clinics dispensing psychedelics for mental health treatment to “expensive spas where customers can go without a diagnosis of mental disorder and have a guided psychedelic experience.” He said:

Readers, including even experts, are falling for a hard sell job by venture capitalists who launder their funding of the study through a nonprofit foundation [i.e., MAPS] and seek not legalization of psychedelics and related illegal drugs but lucrative control over their use for therapeutic and recreational use.

The potential dangers with MDMA are real and even acknowledged by researchers like Jennifer Mitchell, the lead author of “MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD.” She conceded the expense and time intensity of MDMA-assisted therapy and the concern of addiction. In Psychiatrist.com, she said: “Just like all the other amphetamines, you want to be very careful with them, to not over-administer, and to make sure that somebody doesn’t have an addictive tendency to the amphetamine.” You wouldn’t send it home with people to do in their own living room. “You do it in a good, trained treatment facility and that way, you don’t have to worry as much.”

But people will try it at home in their own living room unless its only dispensed in a treatment setting with trained therapists. But this adds to the expense and time intensity of MDMA-assisted therapy. And also leads to Coyne’s expectation of expensive, spa-like treatment centers.

Mitchell thinks younger generations and the prevalence of psychostimulant use among millennials and Gen Zers with ADHD will make them more accepting of psychedelic, MDMA therapies. She also looks to how MDMA has completely transformed some patients. “That’s typically the kind of change that takes years to occur in psychotherapy.”

But this does not change the fact that there is a lack of research on the impact of MDMA on the entire brain and its long-term effects Psychedelic researchers, including MAPS, don’t allow participants in their studies who suffer with comorbidities. The participants are PTSD without co-occurring like the ones noted previously—substance use disorder, eating disorders, depression, autism, compulsive disorders, schizophrenia and anxiety. Mitchell herself said, “We don’t yet know what these compounds in general—but MDMA in particular—do to those people who have these other disorders.” Could it make the depression worse, increase anxiety, or compound the substance use diagnosis in some participants?

Let’s not roll the dice with MDMA and PTSD. And let’s be sure the research studies are done in a way that clearly demonstrates its potential to heal an individual and not just give them a substance use problem or an intensified mental health disorder. Let’s insist that Phase 3 clinical trials for MDM and other psychedelics have at least the recommended 300 participants and a more credibly double-blinded methodology.