Be Careful What You Ask For

Samuel was the last judge to rule over Israel before God granted their desire to have a king rule over them like the other nations around them. Although God had called up a series of judges to deliver and rule Israel since the time of Joshua, they did not have a king ruling over them. It seems they began to suffer from regal envy and political insecurity so they asked Samuel to appoint a king “to judge us like all the nations” (1 Samuel 8:5). Be careful what you ask for, because you just may get it.

Modern governments divide their functions into legislative, executive and judicial departments, but ancient peoples did not always have these clear functional distinctions. So “judges” like Samson, Gideon, Samuel and others were rulers called by God to “judge” or rule Israel for Him in a time of trouble. We see where these rulers were primarily military leaders who delivered Israel from various oppressors. The primary sense of the Hebrew word for “judge” was to govern or rule, and not merely to exercise the more modern judicial function of a judge. But if they did preside over civil, domestic or religious cases judicially (in the modern sense), Israel’s judges were expected to do so with justice and righteousness.

During the early time that Samuel was a prophet and judge over Israel, the Philistines defeated Israel in battle twice, and even captured the ark of God (1 Samuel 4:1-11). But Israel repented of their idolatry and began again to serve the Lord alone, so God delivered them out of the hands of the Philistines (1Samuel 7:3-11). When Samuel became old, he made his sons judges (rulers) over Israel, but they were corrupt: “They took bribes and perverted justice” (1 Samuel 8:3). So the people of Israel told Samuel they wanted a king to rule them like the other nations surrounding them. This request displeased Samuel, so he prayed to the Lord, and God told him to give them what they asked for: appoint a king over them. “For they have not rejected you, but they have rejected me from being king over them” (1 Samuel 8:7). But Samuel was also told by God to warn them what was coming by having a king rule them.

A king would draft their sons into a standing army. He will appoint for himself commanders to the divisions of his army and commandeer their lands for his own use and for his loyal servants. Their daughters would work as cooks, bakers and perfumers for him. He would even tax their grain and vineyards and give the proceeds to his officers and servants. He woul draft their servants and take their donkeys and flocks for his work (1 Samuel 8:11-18).

But the people refused to obey the voice of Samuel. And they said, “No! But there shall be a king over us, 20 that we also may be like all the nations, and that our king may judge us and go out before us and fight our battles.” 21 And when Samuel had heard all the words of the people, he repeated them in the ears of the Lord. 22 And the Lord said to Samuel, “Obey their voice and make them a king” (1 Samuel 8:19-22).

Now there were several good, common sense reasons for the people of Israel to want to have the centralized government of a king ruling (judging) them and fighting their battles. An aspect of ancient kingship was that the rule of law and government was embodied within the ruler. So the book of Judges repeatedly said that since “there was no king in Israel” (Judges 17:6; 18:1; 19:1; 21:25), “everyone did what was right in his own eyes” (Judges 21:25). Also, according to Dillard and Longman in An Introduction to the Old Testament, the time of the book of Judges during the second half of the second millennium B.C. was a time of political and cultural upheaval. The cultures of the Hittites, Minoans and Myceneans were failing and then the Philistines (likely one of the Sea Peoples) settled along the coastal plain of the Mediterranean after a failed attempt to invade Egypt around 1190 B.C. See the follow map found in the Encyclopedia Britannica online.

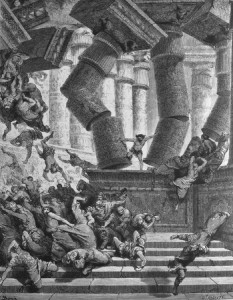

The Philistines expanded into neighbouring areas and soon came into conflict with the Israelites, a struggle represented by the Samson saga (Judges 13–16) in the Hebrew Bible. Possessing superior arms and military organization, the Philistines were able (c. 1050 bce) to occupy part of the Judaean hill country. The Philistines’ local monopoly on smithing iron (I Samuel 13:19), a skill they probably acquired in Anatolia, was likely a factor in their military dominance during this period. They were finally defeated by the Israelite king David (10th century), and thereafter their history was that of individual cities rather than of a people. After the division of Judah and Israel (10th century), the Philistines regained their independence and often engaged in border battles with those kingdoms.

So under the guidance of the Lord, Samuel anointed Saul as the king of Israel (1 Samuel 10:1-8). Since he was tall and handsome, Saul had a kingly appearance (1 Samuel 9:2). After Saul defeated the Ammonites, Samuel reaffirmed his call as king at Gilgal (1 Samuel 11:14). Then Saul drafted his standing army with two thousand men under his command and another thousand under the command of his son, Jonathan. Both Saul and Jonathan had separate victories against the Philistines who then mustered an army of 36,000 against them. As Samuel had done before, he instructed Saul to wait for him seven days at Gilgal, where he would offer sacrifices and then tell Saul what the Lord said he should do.

But Samuel was late, and the army of Israelites under Saul began to desert. So Saul decided to offer the sacrifices himself . But as soon as he finished the burnt offering, Samuel came. When Samuel asked Saul why he failed to wait, he said the people were scattering because Samuel was late and the Philistines had begun to muster at Michmash. So he “forced” himself to offer the burnt offering.

Samuel told Saul he was foolish to disobey the Lord by personally offering the sacrifices instead of waiting for him to arrive. Samuel was still God’s prophet, even if he was no longer the ruler over Israel. Saul made “an executive decision” contrary to the explicit direction of God. As a result, God would not establish his dynasty over Israel. Instead, that would be the privilege of another, who would be a man after the Lord’s own heart (1 Samuel 13:1-14). This, of course, was an allusion to what God would do for David, who was a man after God’s own heart (Acts 13:22) who would have an everlasting dynasty (2 Samuel 7:8-13).

Under pressure, Saul had disobeyed God’s direction to him through the prophet Samuel and did what seemed right in his own eyes at the time. He made what would appear to be a common sense decision—dispense with the preliminary religious ritual and get on with fighting the Philistines before the entire army deserts. His decision showed how his religious behavior and his future actions as king weren’t from a heart devoted to God. Saul was exactly the kind of king Israel had asked for—a king that would rule over them like the other nations surrounding them—following what made sense to his own eyes. The lesson here is to be careful what you ask God for, because you just may get it.