Machiavellian Drug Approval

ProPublica noted that when the FDA’s responsibilities expanded in the 1970s, the review times for new drug approvals began to lag to more than 35 months on the average. The AIDS crisis came soon after, leading activists to accuse the FDA of holding back cures and then press the agency for faster drug approval times. One of the then activists, now an assistant professor of epidemiology at Yale, said they were desperate back then and naively thought there were drugs behind the FDA approval curtain being held back by its slow process. “Thirty years of our rash thinking has led us to a place where we know less and less about the drugs that we pay more and more for.”

The activists’ protests helped bring about the Prescription Drug User Fee Act in 1992, which began drug industry contributions to fund FDA salaries. In return, the FDA promised to speed up review times for drugs—within 12 months for normal applications, and 6 months for priority cases. You can probably guess what happened. The more the FDA relied upon industry fees to pay for drug reviews, the greater was its tendency towards approval. “The virginity was lost in ’92,” according to Jerry Avorn, who is a professor at Harvard Medical School. “Once you have that paying relationship, it creates a dynamic that’s not a healthy one.”

In 1993 Pharma funded 27% of the FDA’s scientific review budgets for branded and generic drugs. In 2017, that had increased to 75% or $905 million. Staffers know you don’t get promoted if you aren’t pro-industry. A former FDA medical team leader said: “You don’t survive as a senior official at the FDA unless you’re pro-industry.” He added the FDA has to pay attention to what Congress says, and the industry will lobby to replace you if they don’t like you. The attitude at the agency is: “Keep Congress off your back and make your life easier.”

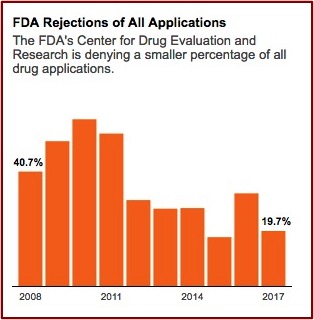

The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research gives internal awards annually to review teams. Former FDA employees said they never saw an award granted to a team that rejected a drug application. Congratulatory emails are sent to review teams by higher-up administrators when a drug is approved. “Nobody gets congratulated for turning a drug down, but you get seriously questioned.” FDA rejections of all drug applications have fallen over 50% since 2008. See the following graph from the above linked article in ProPublica.

Over the past thirty years Congress authorized the FDA to implement at least four major routes to faster approvals. Initially, these pathways were supposed to be the exception to the rule, but now they seem to have become the rule. In 1988 Congress authorized the FDA to create “fast track” regulations. In 1992 the Prescription Drug User Fee Act formalized “accelerated approval” and “priority review.” Then when the law was reauthorized in 1997, the goal for review times was lowered to ten months. Finally, in 2012, the designation of “breakthrough therapy” enabled the FDA to waive normal procedures for drugs “that showed substantial improvement over available treatments.”

Over the past thirty years Congress authorized the FDA to implement at least four major routes to faster approvals. Initially, these pathways were supposed to be the exception to the rule, but now they seem to have become the rule. In 1988 Congress authorized the FDA to create “fast track” regulations. In 1992 the Prescription Drug User Fee Act formalized “accelerated approval” and “priority review.” Then when the law was reauthorized in 1997, the goal for review times was lowered to ten months. Finally, in 2012, the designation of “breakthrough therapy” enabled the FDA to waive normal procedures for drugs “that showed substantial improvement over available treatments.”

Sixty-eight percent of novel drugs approved by the FDA between 2014 and 2016 qualified for one or more of these accelerated pathways, Kesselheim and his colleagues have found. Once described by Rachel Sherman, now FDA principal deputy commissioner, as a program for “knock your socks off, home run” treatments, the “breakthrough therapy” label was doled out to 28 percent of drugs approved from 2014 to 2016.

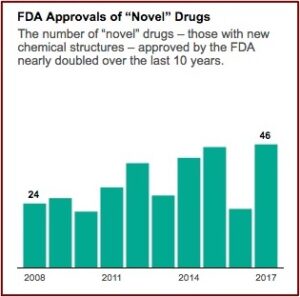

The industry’s lobbying group, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), is pressing for even faster approvals. A policy memo on its website warns of “needless delays in drug review and approval that lead to longer developmental times.” Aaron Kesselheim, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School said he thought it was reasonable to want to move drugs faster, particularly for “an extremely promising new product, which treats a serious or life-threatening disease.” When you do that, he said the key factor “is that you’ve got to make sure you closely follow the drug in a thoughtful way and unfortunately, too often we don’t do that in the U.S.” FDA approvals of novel drug applications have nearly doubled since 2008. See the following graph from the above linked article in ProPublica.

Nuplazid, a drug for hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease, was an example of the potential consequences from this accelerated approval process in Caroline Chen’s article for ProPublica. The drug was created in 2001 by a chemist at Acadia Pharmaceuticals. In 2009 it failed to prove its benefit over a placebo in the first of two Phase 3 clinical trials; two successful Phase 3 trials are required. The company halted the second trial and asked the FDA for permission to revise the scale used to measure benefit. They argued the original scale was typically used for schizophrenia assessments and thus wasn’t appropriate for Parkinson’s-related psychosis.

Nuplazid, a drug for hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease, was an example of the potential consequences from this accelerated approval process in Caroline Chen’s article for ProPublica. The drug was created in 2001 by a chemist at Acadia Pharmaceuticals. In 2009 it failed to prove its benefit over a placebo in the first of two Phase 3 clinical trials; two successful Phase 3 trials are required. The company halted the second trial and asked the FDA for permission to revise the scale used to measure benefit. They argued the original scale was typically used for schizophrenia assessments and thus wasn’t appropriate for Parkinson’s-related psychosis.

Given that Acadia didn’t raise this issue with the FDA until after its failed clinical trial, their objection seems like sour grapes to me. Why didn’t they use the revised scale from the beginning? Nevertheless, the FDA agreed to this new scale—even though it had never been used before in a study for drug approval! Then, since there were no treatments approved for Parkinson’s-related psychosis, the FDA granted Acadia’s request for break-through therapy status, meaning Nuplazid now only needed one positive Phase 3 clinical instead of two for approval. “In 2012, Acadia finally got the positive trial results it had hoped for. In a study of 199 patients, Nuplazid showed a small but statistically significant advantage over a placebo.”

An FDA medical reviewer was skeptical of Nuplazid. In analyzing all of the drug’s trial results, he calculated you would have to treat 91 patients to get seven who would receive the full benefit. Five of those 91 would suffer “serious adverse events,” including one death. He recommended against approval, citing “an unacceptably increased, drug-related, safety risk of mortality and serious morbidity.” So the FDA convened an advisory committee to help it decide. That committee eventually voted 12-2 to recommend accelerated approval.

Fifteen members of the public testified at its hearing. Three were physicians who were paid consultants for Acadia. Four worked with Parkinson’s advocacy organizations funded by Acadia. The company paid for the travel of three other witnesses who were relatives of Parkinson’s patients, and made videos shown to the committee of two other caregivers. Two speakers, the daughter and granddaughter of a woman who suffered from Parkinson’s, said they had no financial relationship with Acadia. However, the granddaughter is now a paid “brand ambassador” for Nuplazid. All begged the FDA to approve Nuplazid. . . . The only speaker who urged the FDA to reject the drug was a scientist at the National Center for Health Research who has never had any financial relationship with Acadia.

Since Nuplazid was approved in 2016, Acadia raised its price twice from the original base price of $24,000 to more than $33,000. “There have been 6,800 reports of adverse events for patients on the drug, including 887 deaths” as of March 31st of 2018. In more than 400 instances Nuplazid was associated with worsening hallucinations—“one of the very symptoms it was supposed to treat.” After a CNN report about adverse events related to Nuplazid in April of 2018, the FDA began an evaluation. There are more examples of drugs-gone-bad after approval in the article.

Although the FDA expedites drug approvals, it will wait ten years or more for the post-marketing studies manufacturers agree to do when their drug is approved. Studies on Nuplazid aren’t expected until 2021. One of the reasons post-marketing studies take so long to complete is the fact it’s harder to recruit patients to risk being given a placebo when the drug is available on the market. In addition, the manufacturer no longer has a financial incentive to study its impact since the drug is on the market and could lose money if the results are negative. “Of post-marketing studies agreed to by manufacturers in 2009 and 2010, 20 percent had not started five years later, and another 25 percent were still ongoing.”

The FDA has the authority to issue fines or pull a drug from the market if a manufacturer doesn’t meet its post-marketing requirements. “Yet the agency has never fined a company for missing a deadline.” The agency would have the burden to show the company was dragging its feet, which could be difficult to prove. “It’d be an administrative thing that companies could contest,” according to the FDA director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

Michael Carome, the director of the health research group for Public Citizen, a nonprofit advocacy organization, said instead of a regulator and a regulated industry, we now have a partnership. “That relationship has tilted the agency away from a public health perspective to an industry friendly perspective.”

In “FDA’s revolving door,” Charles Piller pointed out how many former FDA employees end up working or consulting for the drug makers they previously regulated. There are safeguards that are supposed to prevent the prospect of industry employment from affecting an employee’s decisions while at the agency. And there are others to discourage them from exploiting relationships with former colleagues after they leave. But the reality seems to be somewhat different. Piller cited a 2016 BMJ article that found 15 of 26 FDA employees who had conducted reviews over a 9-year time period in the hematology oncology field later worked or consulted for the biopharmaceutical industry.

Science has discovered that 11 of 16 FDA medical examiners who worked on 28 drug approvals and then left the agency for new jobs are now employed by or consult for the companies they recently regulated. This can create at least the appearance of conflicts of interest.

The co-author of the 2016 BMJ study thought that weak federal restrictions and the expectation of future employment inevitably biases how FDA staffers conduct drug reviews. “When your No. 1 major employer after you leave your job is sitting across the table from you, you’re not going to be a hard-ass when you regulate. That’s just human nature.” No, that’s not human nature, it’s just plain Machiavellian behavior—whether you’re doing whatever it takes to get your drugs on the market or whether you’re trying to position yourself for a future job with Pharma as you regulate their drugs.