The Trickery of Drug Approval

From all that the public is hearing and seeing about the COVID vaccines, both the pharmaceutical companies and the FDA have done an amazing job bringing the first two vaccines to market. In order to alleviate public mistrust of the “warp speed” development process, Dr. Anthony Fauci and NIH director Francis Collins publicly received their first dose of the Moderna vaccine. Dr Fauci said it was remarkable to be receiving it less than a year after the virus it treated was discovered. “What we’re seeing now is the culmination of years of research which have led to a phenomenon that has truly been unprecedented.” But will the pharmaceutical companies continue this standard of fast, safe and effective drug development?

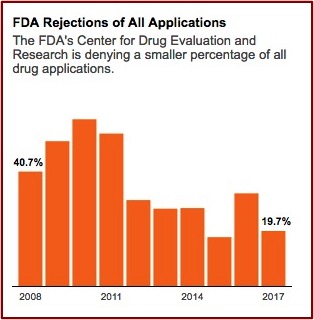

In January 2020, just before the emergence of the pandemic, Harvard Medical School researchers published a study in JAMA that found the FDA is approving new drugs more quickly than ever before and using less stringent standards to determine if the drugs actually work. The lead author of the study told NPR “There has been a gradual erosion of the evidence that’s required for FDA approval.” As a result, patients and doctors “should not expect the new drugs will be dramatically better than older ones.” The use of expedited programs (Accelerated Approval, Fast-Track, and Priority Review) for new drugs increased over time, with 81% of new drugs benefiting from at least one such program in 2018. NPR reported the study found the median review time for standard drug applications was just over 10 months in 2018 compared to 2.8 years for standard and priority applications from 1986 through 1992.

The proportion of new approvals supported by at least 2 pivotal trials decreased from 80.6% in 1995-1997 to 52.8% in 2015-2017, based on 124 and 106 approvals, respectively, while the median number of patients studied did not change significantly (774 vs 816). FDA drug review times declined from more than 3 years in 1983 to less than 1 year in 2017. But total time from the authorization of clinical testing to approval has remained at approximately 8 years over that period.

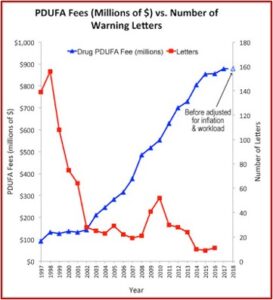

Drug makers began to pay FDA fees to fund the review process as a result of AIDS activists protesting the slowness of the agency in the 1980s. In 1993, the first year after Congress passed the Prescription Drug User Fee Act, the FDA collected $29 million in fees. That amount rose to $908 million in 2018. The industry fees amounted to around 80% of the money spent on FDA employee salaries for drug reviews that year. The lead author of the JAMA study said: “There is some concern about the incentives that this created within the FDA … And whether it has created a culture in the FDA where the primary client is no longer viewed as the patient, but the industry.”

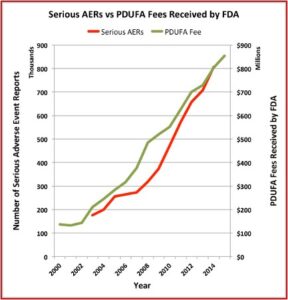

The Pharma Marketing Blog tracked the relationship of fees paid to the FDA by the pharmaceutical industry and the push for less rigorous scientific proof in clinical trials (and therefore faster drug approvals). He noted that there was a negative correlation between the rise in user fees and a drop in the number of warning letters sent out by the FDA to companies. There was also a positive correlation between drug user fees and adverse event reports, which track drug safety. See the following graphs taken from the Pharma Marketing Blog.

This hasn’t been the only recent evidence of how the pharmaceutical industry seems to be replacing patients as the FDA’s primary clients. Researchers published a study of the “Association between FDA and EMA [European Medicines Agency] expedited approval programs and therapeutic value of new medicines” in the October 2020 issue of the BMJ. The study sought to characterize the therapeutic value of new drugs approved by the FDA and EMA and how these ratings were associated with the regulatory approval process of the expedited programs of the FDA and EMA.

This hasn’t been the only recent evidence of how the pharmaceutical industry seems to be replacing patients as the FDA’s primary clients. Researchers published a study of the “Association between FDA and EMA [European Medicines Agency] expedited approval programs and therapeutic value of new medicines” in the October 2020 issue of the BMJ. The study sought to characterize the therapeutic value of new drugs approved by the FDA and EMA and how these ratings were associated with the regulatory approval process of the expedited programs of the FDA and EMA.

Over the past few decades both agencies have established programs to expedite drug development for serious conditions. The four main expedited programs of the FDA are: fast track (introduced in 1987), accelerated approval (1992), priority review (1992), and breakthrough therapy (2012). Emergency use authorization, under which the COVID-19 vaccines have been expedited, technically isn’t an FDA approval of the drug, but it authorizes the FDA to facilitate an unapproved product during a declared state of emergency. Its latest update occurred in 2017. The EMA has two expedited programs, accelerated assessment (2005) and conditional marketing authorization (2006). The EMA instituted a third program, PRIME, the priority medicines scheme, in 2016.

These expedited programs were intended to prioritize the most important medicines for faster access to patients, and are increasingly the route by which new medicines are approved. For example, the FDA approved 60% of new drugs through at least one expedited program in 2019, while only 34% of drug approvals in 2000 were expedited. The FDA and EMA guidance indicated that an expedited program should be reserved for drugs that are expected to show an improvement over the available therapies. “However, neither the FDA nor the EMA specifically requires data on, or makes regulatory approval contingent on, comparative effectiveness; most new drugs are approved on the basis of placebo-controlled trials or single arm studies.”

This means the therapeutic value of medicines that benefitted from the FDA and EMA expedited programs is uncertain. Using ratings of therapeutic value published by health authorities in four countries and an independent non-profit organization, the researchers “evaluated the association between expedited programs and ratings of therapeutic value for all new drugs approved by the FDA and EMA from 2007 through 2017.”

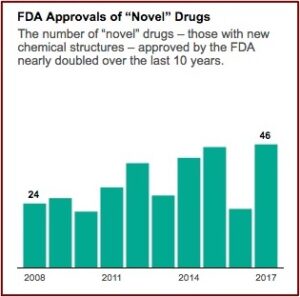

We found that less than a third of all new drugs approved by the FDA and EMA were rated by any of five independent organizations as having high therapeutic value—that is, providing moderate or better improvement in clinical outcomes for patients. Most of the increase in the number of new drug approvals over the past decade was driven by drugs rated as having low therapeutic value, which calls into question the common practice of using simple counts of new drug approvals as a measure of innovation. Rather, a more nuanced view of innovation is needed that takes into account the clinical benefits and relevance to patients of new medicines.

The study’s findings suggest that after FDA regulatory approval, there is a widening gap between the drug’s approval and the clinical and public health priorities of health systems, payers and patients in drug safety and efficacy. Contributing to this gap is the varying quality of clinical evidence available at the time of approval. This leads to uncertainty around the extent of clinical benefit of the respective drug. The study’s data emphasizes the importance of robust post marketing evaluation for expedited drugs. “Such an evaluation would confirm early evidence of efficacy and help to elucidate findings from several previous studies suggesting that accelerated approval, priority review, and fast track drugs were associated with increased safety related reports or labeling changes.”

The researchers suggested one step leading to greater assurance of timely completion of post marketing study requirements for expedited drugs could be to require that certain mandated studies enroll patients before the FDA or EMA grants approval. They also suggested that regulatory agencies explore whether additional explanations were necessary. These explanations could include elaboration in product labeling, press releases, or approval documents. They could provide more realistic expectations of benefit for expedited drug approvals by patients and clinicians. Their findings also had implications for the controversy around drug prices.

In the US, the largest public payers are required by law to cover most (Medicaid) or a substantial number (Medicare) of drugs approved by the FDA, regardless of the quality of the evidence supporting their approval or their therapeutic value. Previous studies of cancer drugs have found no association between clinical benefit and drug prices and reimbursement.

In conclusion, the researchers said while the FDA and EMA are increasingly using expedited programs to facilitate drug development, the absolute value of highly rated drugs approved by the FDA and EMA over the past decade was low. Policy makers could explore implementing therapeutic value ratings more widely for new drug approvals. This would align the evidentiary needs of regulatory approval and reimbursement decisions with informing patients and doctors about the benefits and risks of new drugs, particularly those approved by expedited programs.

It’s not so surprising, then, that so many Americans are hesitant to say they plan to get a coronavirus vaccine. It seems that the above discussed results of research into new drug development by the pharmaceutical companies is at least partly to blame. Many people do not trust the claims drug companies make about their products.

The Pew Research Center conducted a survey of Americans at the end of November 2020. Sixty percent said they would definitely or probably get a vaccine for the coronavirus, which was up from 51% in September. Thirty-nine percent say they will definitely or probably not get a coronavirus vaccine. About half of this group, 18%, said it’s possible they would decide to get vaccinated once people start getting vaccinated and there is more information available. “Yet, 21% of U.S. adults do not intend to get vaccinated and are ‘pretty certain’ more information will not change their mind.”

While public intent to get a vaccine and confidence in the vaccine development process are up, there’s considerable wariness about being among the first to get a vaccine: 62% of the public says they would be uncomfortable doing this. Just 37% would be comfortable.

Public confidence has increased since September that the research and development process will yield a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19. Seventy-five percent of individuals now have a great deal or fair amount of confidence in the R&D process. However, one of the factors influencing whether someone intends to get a vaccine for COVID-19 is mistrust of the vaccine development process. Sixteen percent of Americans do not have much confidence in the process; 8% have no confidence that the R&D process will produce a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19. Confidence in scientists remains slightly higher than before the pandemic.

With scientists and their work in the spotlight, 39% of Americans say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest, an uptick from 35% who said this before the pandemic took hold. Most Americans have at least a fair amount of confidence in scientists. However, ratings of scientists are now more partisan than at any point since Pew Research Center first asked this question in 2016: 55% of Democrats now say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists, compared with just 22% of Republicans who say the same.

Pharmaceutical companies have an opportunity when they resume the research and development process for new drug applications after the pandemic. Will they continue to use external committees of scientists vetting the data for new drug applications and produce truly independent recommendations and rejections? If pharmaceutical companies can maintain an open and transparent R&D process and develop drugs with a truly high therapeutic value, the confidence level of patients and their doctors would be higher than ever. For more on COVID, see “Learning from COVID Drug Development.”