Is There a Better Way to Prevent Overdose Deaths?

The CDC released provisional data suggesting opioid overdose deaths dropped to the lowest level in three years. The newest CDC update indicated the provisional decline reflects data through April of 2024. An Associated Press report said experts reacted cautiously to the reported drop. It was only the second annual decline in more than 30 years, and it was also relatively small. One expert thought it should be understood more as a leveling off; another observed the previous decrease in 2018 was followed by an increase afterwards.

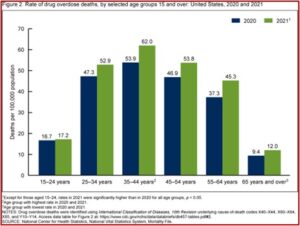

Nevertheless, the CDC Chief Medical Officer thought the dip was “heartening news,” but “there are still families and friends losing their loved ones to drug overdoses at staggering numbers.” A study reported in May of 2024 in JAMA Psychiatry found that an estimated 321,566 children lost a parent to drug overdose in the US from 2011 to 2021. The rate of children who lost a parent to drug overdose per 100,000 children increased from 27.0 per 100,000 to 63.1 per 100,000 in 2021. There were significant differences across racial and ethnic groups, with the highest rates among children of non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native individuals, who had a rate of 187.1 per 100,000 in 2021. This was more than double the rate among children of non-Hispanic White individuals (76.5 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic Black individuals (73.2 per 100,000).

Given the potential short- and long-term negative impact of parental loss, program and policy planning should ensure that responses to the overdose crisis account for the full burden of drug overdose on families and children, including addressing the economic, social, educational, and health care needs of children who have lost parents to overdose.

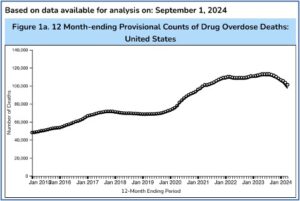

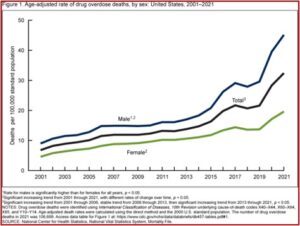

According to the CDC, around 107,500 people died of overdoses in the U.S. in 2023, which was down 3% from 2022 when there were an estimated 111,000 such deaths. There have been more than 1 million drug overdose deaths since 1999. An August 14th CDC update of that data had a graph that showed the 2018 leveling off was followed by a dramatic increase after the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020. See the following figure taken from the CDC update.

The update reported the overall decrease of overdose deaths in the U.S. was 12.2%. Yet the interactive maps indicated several Western states had overdose rates that were as high or higher than reported previously. Alaska (41.82%), Oregon (15.11%), Nevada (13.33%), and Washington (10.03%) all reported double digit increases. Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Hawaii, and Iowa also reported increases. Nebraska (29.95%) and North Carolina (41.81%) had significant decreases. However, the “reported provisional counts may not include all deaths that occurred during a given time period.” These delays are because they require lengthy investigation, including toxicology testing.

Commenting on the same CDC update, CBS News reported at its peak last summer, the U.S. had more than 86,000 estimated deaths. This compared to the CDC estimate of 75,091 opioid overdose deaths for the year ending in April 2024. “The pace of opioid overdose deaths still remains far worse than before the pandemic, when there were fewer than 50,000 fatal overdoses a year.” Fatal overdoses from drugs other than opioids have been decreasing as well. But the individuals who overdosed aren’t the only victims.

Campaigning on Overdoses

Not surprisingly, CBS News noted how overdose deaths became part of the 2024 presidential campaign rhetoric. Former president Trump said overdoses were lower during his term. Technically, he was correct. The figures were lower during his tenure as the 45th president of the United States from January 2017 to January 2021 than they are currently. But according to CDC data, the overdose increases began around March of 2019. During the Trump presidency, overdose deaths grew from 66,571 in the twelve months before January 2017 to 94,788 in the twelve months before January 2021, an increase of 29.8%.

The former president said he wanted to work with states to force homeless addicts into treatment and punish drug dealers with the death penalty. Both Trump and Harris have tied curbing drug overdoses to immigration and border issues. But Trump incorrectly claimed overdose deaths were up 18% “under Kamala.” Assuming he meant during the tenure for Joe Biden who became president in January of 2021, overdose deaths were reported to be 94,778 in January of 2021, and 97,309 in April of 2024, a 2.6% increase.

Notice that there was an effect of when the reported CDC data on overdose deaths was collected after the COVID-19 pandemic began. For example, at the time the WHO reported the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March of 2020, there had been 74,679 overdose deaths in the previous 12 months. In March of 2021, there were 98,211 reported overdose deaths, an increase of 24% in the first year of the pandemic. This dramatic increase of overdose deaths in the first year of the pandemic occurred during the last year of Trump’s presidency.

The FDA first granted emergency use authorization to the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID vaccine on December 10, 2020, followed by the Moderna vaccine on December 17, 2020, and the Janssen vaccine on February 27, 2021. By April 19, 2021 all U.S. states had opened vaccine eligibility to residents 16 and over. By March of 2022, reported overdose deaths were 108,604 in the 12 previous months, an increase of 9.6%. By March of 2023, the previous 12 months of reported overdose deaths were 110,082, an increase of 1.4%. By March of 2024, reported overdose deaths were 100,518 for the previous 12 months, a decrease of 8.7%.

The variance of the increase in overdose deaths dropped from a high of 24% in the first year of the pandemic, to an increase of only 1.4% in 2023, and was followed by an 8.7% decrease in March of 2024, three years after the availability of the COVID vaccines in the U.S. This suggests it had nothing to do with who was president or vice president; or which political party was in power.

As noted above, there have been over a million overdose deaths since 1999. CDC data indicated there were 47,523 overdose deaths in the 12 months before January 2015, and 72,124 overdose deaths in the 12 months before January 2020, an increase of 34%. So, overdose deaths were a public health problem independent of the pandemic.

Preventing Overdose Deaths Through a Drug-Centered Model of MAT

In order to address this public health problem, the National Institutes of Health launched the HEALing Communities Study (HCS) in 2019. “It was the largest addiction prevention and treatment implementation study ever conducted.” It targeted 67 communities in four states (Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York and Ohio) that had been hit hard by the opioid crisis. The goal was to test the impact of an integrated set of evidence-based interventions for preventing overdose and treating opioid misuse in communities that were highly impacted by the opioid crisis.

The findings of the HCS study were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The Communities That HEAL (CTH) intervention focused on a harm reduction approach, with education about overdose prevention and naloxone distribution, the use of methadone and buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder, and safer opioid prescribing, dispensing and disposal practices. Yet, “despite the breadth and depth of the intervention, the risk of opioid-related overdose death was similar in the intervention group and the control group.” In other words, there were no statistically significant differences.

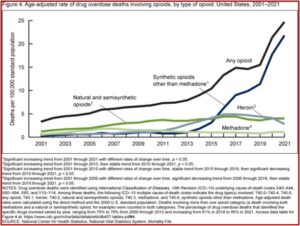

The researchers first said the time frame to implement the various strategies was insufficient. Secondly, they thought the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the capacity of communities to implement the Communities That HEAL (CTH) intervention. Thirdly, changes in the illicit drug market occurred with fentanyl becoming more prevalent, indications that it was used as an adulterant with stimulants and it also began appearing in counterfeit pills. Additionally, there were challenges from the growing use of xylazine in illicit opioids. For more information on xylazine, see “Tranq Dope and Its Consequences” and “Flesh Eating Tranq Dope.”

Attempting to put a positive spin on the disappointing results, a NIH news release from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in June of 2024 said that despite “unforeseen challenges,” the HCS successfully engaged communities to implement hundreds of evidence-based strategies, “demonstrating how leveraging community partnerships and using data to inform public health decisions can effectively support the uptake of evidence-based strategies at the local level.” The NIDA director, Nora Volkow said:

Yet, particularly in the era of fentanyl and its increased mixture with psychostimulant drugs, it’s clear we need to continue developing new tools and approaches for addressing the overdose crisis. Ongoing analyses of the rich data from this study will be critical to guiding our efforts in the future.

Then the leader of SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) said:

This study recognizes there is no quick fix to reduce opioid overdose deaths. Saving lives requires ongoing commitment to evidence-based strategies. The HEALing Communities Study facilitated the implementation of 615 evidence-based practice strategies, with the potential to yield lifesaving results in coming years.

However, I believe an additional problem with the results of the HCS study was the various intervention strategies were based on a disease-centered model of drug action. NIDA and SAMHSA need to view MAT and opioid use disorder through the lens of a drug-centered model of medication action and adjust their intervention strategies accordingly.

Joanna Moncrieff describes two different types of drug action, the disease-centered model and the drug-centered model. The disease-centered model underlies the psychopharmacology presumed in current MAT. Its theoretical assumptions about how psychotropic drugs work are rarely discussed explicitly. This assumes psychotropic medications like buprenorphine help to correct a biochemical abnormality. For more on Moncreiff’s models of drug action, see “Rethinking Models of Psychotropic Drug Action.”

William White has tried for years to build bridges between the two philosophically-opposed positions on the use of MAT. In “From Bias to Balance,” he described them as “medication haters” and “medication advocates.” White said medications can play a valuable role in harm reduction, but we do addiction treatment a disservice if we portray medication alone as a panacea for the cure of opioid addiction, which seems to be what the HCS study did. He added:

Medications are best viewed as an integral component of the recovery support menu rather than being THE menu, and their value will depend as much on the quality of the milieus in which they are delivered as any innate healing properties that they possess. If the effectiveness of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) programs is compromised by low retention rates, low rates of post-med. recovery support services, and high rates of post-medication addiction recurrence, as this review suggests, then why are we as recovery advocates not collaborating with MAT patients, their families, and MAT clinicians and program administrators to change these conditions?

According to White, the addiction treatment field has yet to reach consensus on what is the optimal duration of medical support in the treatment of opioid use disorder. I think this impasse partly reflects the unacknowledged presumption of Moncrieff’s disease-centered model of drug action among medication advocates. The disease-centered model is itself a product of what is called the medical model, which sees psychopathology as the result of biology; a physical/organic problem in brain structures, neurotransmitters, etc. The over reliance on the medical model perspective (and the disease-centered model of drug action) in addiction treatment leads to an imperfect conception of substance use and a distorted understanding of the risks and benefits of buprenorphine and methadone when they are used to treat opioid use disorder.

There is no pharmacological difference between drugs used for psychiatric purposes and other recreational or psychoactive drugs. They all act on the nervous system to produce a state of altered consciousness, a state that is distinct from the normal undrugged state; a drug is a drug, is a drug. We need to develop a better way to prevent overdose deaths. The evidence-based interventions of HCS need to see their prevention attempts with MAT through the lens of a drug-centered model of drug action.

For more information on William White and the disease-centered versus the drug-centered models of drug action, see: “The Complexities and Limitations of Buprenorphine” Parts 1 and 2.