Common Grace & “The Triangle of Self Obsession,” Part 2

In “The Blame Game: Accepting Accountability” Gina M. asked how many times you have made a poor choice out of spite, or a defense mechanism, or in reaction to something done to you? She said it took her a long time to admit that she had been playing the blame game for much of her life. She said she had been living in the triangle of self-obsession—anger, fear, and resentment. More and more everyday she’s realized how often she uses the excuse of “what’s happened to me” as a cop-out for every poor choice she’s ever made.

But the reality is that I was just rewarding my self-pity, living in the triangle of self-obsession, finding every excuse in the book for my questionable behavior. I was playing the blame game just so I had a “reason to.” A reason to deceive myself. A reason to justify my poor choices…because it was too hard to accept the fact that sometimes I actually do make poor choices. And because those poor choices carried more shame, guilt and regret than I cared to admit, because I was a people pleaser who lacked self-love and self-respect, my fear of judgement led me straight into a triangle of self-obsession.

In Part 1, we pointed out how common grace and the triangle of resentment, anger and fear could be applied to the consequences of Adam and Eve eating of the tree which God commanded Adam not to eat. Recall that it was said NA literature was a common grace description of how God restrains drug addiction and alcoholism. Recovery is God’s bounty poured out on all people in order for them to recover, regardless of their faith in Him. It won’t save them from their sin, but it can prevent them from the further guilt, shame and unmanageability of an active addiction. Here in Part 2, we’ll unpack the common grace found in “The Triangle Self-Obsession,” where it said self-obsession was at the heart of addictive insanity.

Not realizing she had affirmed what I’ve called the common grace of recovery, Gina M. said it was not just addicts who could benefit from the self-discovery recovery brings. “You don’t need to be an addict to hold resentments, to be angry, or to feel fear.” She said she was “learning to replace anger with love, resentment with acceptance, and fear with faith.”

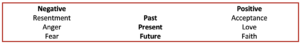

“The Triangle of Self-Obsession” said resentment is the way most addicts (or most people) react to their past. This resentment was reliving past experiences over and over again. Anger is how most people deal with the present. “It is their reaction to and denial of reality.” Fear is what we feel when we think about the future. “It is our response to the unknown.”

NA pictured the way we react to people, places, and things as follows:

All three of these things are expressions of our self-obsession. They are the way that we react when people, places and things (past, present, and future) do not live up to our demands.

In Narcotics Anonymous we are given a new way of life and a new set of tools. These are the Twelve Steps, and we work them to the best of our ability. If we stay clean, and can learn to practice these principles in all our affairs, a miracle happens. We find freedom—from drugs, from our addiction, and from our self-obsession. Resentment is replaced with acceptance; anger is replaced with love; and fear is replaced with faith.

Following the distinction between spiritual and religious made by AA, Alcoholics Anonymous, NA avoids beliefs or doctrines that it sees as institutional religion. NA and AA follow the thought of William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience, who saw institutional religion as worship, sacrifice, ritual, theology, ceremony and ecclesiastical organization. Personal religion or spirituality for James was “the feelings, acts and experiences of [the] individual . . . in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider to be divine.” In the broadest sense possible, this spirituality consisted in the belief that there was an unseen order to existence; where supreme good lay in harmoniously adjusting to that order.

“The Triangle of Self-Obsession” said seeking help from belief in a Power greater than yourself was a natural part of growing up, but here it stumbles. Belief in Adam and Eve, accepting the reality of the story of the birth of original sin and the promise of salvation in the protevangelium is theology—part of institutional religion—which it avoids. So, it must have a nonreligious explanation for why people become addicts. It does this by describing how when people are born, they are only conscious of themselves, “we are the universe;” we are self-centered. As we grow up, we realize the outside world cannot provide all our wants and needs, and we begin to supplement what is given to us with our own efforts.

As this dependency on people, places, and things decreases, we increasingly rely on ourselves to meet our wants and needs. We become more self-sufficient “and learn that happiness and contentment come from within.” As we grow and mature, we recognize not only our strengths, but also our weaknesses and limitations. And most people develop a belief in a “Power greater than themselves to provide the things they cannot provide for themselves.” Here is where addicts are said to “falter along the way.”

We never seem to outgrow the self-centeredness of the child. We never seem to find the self-sufficiency that others do. We continue to depend on the world around us and refuse to accept that we will not be given everything. We become self-obsessed; our wants and needs become demands. We reach a point where contentment and fulfillment are impossible. People, places, and things cannot possibly fill the emptiness inside of us, and we react to them with resentment, anger, and fear.

Without a belief in a Power greater than ourselves that can be trusted to provide the things we cannot provide for ourselves, the addict cannot grow out of childish self-centeredness. Their wants and needs of people, places, and things become demands that are impossible to fulfill. This leads to a negative reaction to that failure with resentment, anger, and fear. It cannot be a sinful reaction to not getting their wants and needs met, since sin is religious.

Instead of fallen, sinful human nature, NA says addicts have a metaphorical “disease” that forces them to seek help from a greater Power, one that Christians confess to be Jesus Christ, who is the same yesterday, today and forever (Hebrews 13:8). Relating Hebrews 13:8 to the above diagram from “The Triangle of Self-Obsession,” we’d say Jesus is the same in the past, present and future. “We are fortunate that we are given only one choice; one last chance. We must break the triangle of self-obsession; we must grow up, or die.”

To the Christian who believes in the truth and reality of the Genesis story of the Fall of Adam and Eve and the origins of sin, “The Triangle of Self-Obsession” will seem to be an incomplete explanation of how addicts “falter along the way.” But it can be used as a point of contact to explore a deeper, and truer sense of spirituality and religion beyond that of William James, NA, or AA. See “Is AA Religious?” and “Religious Alcoholics; Anonymous Spirituality” for a discussion of the differences between true religion and mere religion; true spirituality and mere spirituality.