Heresy, Canon and the Early Church, Part 2

By the close of the second century an outline of the New Testament had appeared. While there were some disputes about its fringes, the nucleus of the NT canon had formed. “By the end of the third century and the beginning of the fourth century, the great majority of the twenty seven books [of the New Testament] … were almost universally acknowledged to be authoritative,” according to Bruce Metzger. Ironically, this process seems to have been helped along by early heretics of Christian belief like the Gnostics, Marcion and Montanus.

Gnosticism was a syncretistic religion and philosophy that thrived for about four hundred years alongside Christianity. Gnostics stressed salvation through gnõsis (knowledge) that would free the divine spark within elect souls, allowing it to escape from the fallen physical world and return to the realm of light. The physical body was a prison that trapped this “divine spark.”

The extensive literature developed by the Gnostics had a twofold purpose. First, it was to instruct believers about their origins and the structure of the visible world and the worlds above. Second, and most importantly, it was the means by which one could conquer the powers of darkness and return to the realm of the highest God. There were Gnostic “gospels” and other documents such as: the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, the Apocryphon of John, and the Hypostasis of the Archons. These and other Gnostic codices are from the Nag Hammadi library, found near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945. The library is estimated to be from around 400 AD.

There are three features that appear to be characteristic of several Gnostic systems. First, there was a philosophical dualism that rejected the visible world, seeing it as alien to the supreme God. Second, there was a belief in a subordinate deity, the Demiurge, who was responsible for the creation of the world. And third, there was a radical distinction between Jesus and the Christ, leading to the Docetic belief that Christ the Redeemer only appeared to be a real human being.

The church countered Gnostic beliefs by stating nothing from their systems was found in the four Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles of Paul. The Gnostics acknowledged this, but claimed their teachings were communicated “only to his most trusted disciples” and not to the general public. For proof, they appealed to a number of their ‘gospels.’ These gospels often dealt with the period between the resurrection and the ascension of Christ, a time that the canonical Gospels say very little. There were also other Gnostic texts in which they claimed the apostles reported what the Lord said to them in secret.

The primary role played by Gnosticism in developing the NT canon was to motivate the true followers of Christ “to ascertain more clearly which books and epistles conveyed the true teaching of the Gospel.” Bruce Metzger said:

It was not easy for the Church to defend herself against Gnosticism. Certain elements in the gospel tradition itself seemed to give verisimilitude to the Gnostics’ claim. . . . One can understand that in defending itself against Gnosticism, a most important problem for the church was to determine what really constituted a true gospel and a genuine apostolic writing. In order to prevent the exploitation of secret traditions, which were practically uncontrollable, the Church had to be careful to accept nothing without the stamp of apostolic guarantee.

But before the Gnostic problem was resolved, there was Marcion, a wealthy Christian ship-owner who arrived in Rome around 140 AD. He became a member of one of the Roman churches and made a few large financial contributions to the Church. At the end of July in 144 he was invited to expound his teachings before the clergy of the Christian congregations in Rome, hoping to win others to his point of view. “The hearing ended in a harsh rejection of Marcion’s views.” He was formally excommunicated and his money returned. But he persisted in attempting to win others to his views and although he died in 160, by the end of the second century his teachings had become a serious threat to the mainstream Christian church.

Marcion believed in two gods—the Supreme God of goodness and the God of justice, who was the Creator and God of the Jews. The deficiencies of the creation point to a deficient god. He rejected the entire Old Testament, refusing to admit it was part of the authoritative Christian Scriptures at all. Jesus was sent as a messenger of the supreme God to offer humanity an escape from the creator-god and his deficient world. Since Jesus was sent by the creator-God, he was not part of creation. He was a divine being who only seemed to be human. What followed from his Christology was that Marcion rejected the virgin birth and taught that Jesus did not suffer and die on the cross; he only appeared to do so.

Marcion believed that Paul alone of the New Testament writers understood the significance of Jesus as the messenger of the Supreme God. He only accepted the authority of the nine Pauline epistles written to the churches and Philemon. He rejected the authority of Paul’s pastoral epistles to Timothy and Titus. He also freely removed passages where Paul had commented favorably on the Law or quoted the OT. For example, he deleted Galatians 3:16-4:6 because of its reference to Abraham and his descendents. Marcion only trusted the Gospel of Luke, but again heavily edited it, removing most of the first four chapters, because of his belief Jesus could not have been born of a woman since he was divine.

In addition to making the deletions of all that involved approval of the Old Testament and the creator god of the Jews, Marcion modified the text through transpositions and occasional additions in order to restore what he considered must have been the original sense.

The authority of the four Gospels had reached a consensus and confidence in which documents were the true apostolic writings had placed them alongside the Gospels during the first half of the second century. Marcion’s canon accelerated this crystallization of the church’s canon by forcing orthodox Christians to state more clearly what they already believed. “It was in opposition of to Marcion’s criticism that the Church first became fully conscious of its inheritance of apostolic writings.”

Into the heretical mix of the second century came Montanism, which began in Phrygia around 156. The movement was named after Montanus, who is sometimes said to have been a priest of Cybele, a pagan cult whose activity was also centered in Phyrgia (located in the Western part of modern Turkey). Montanus fell into a trance soon after his conversion and began to speak in tongues. He announced that he was the ‘Paraclete’ Jesus had promised to send in John’s Gospel (14:15-17; 17:7-15). He is reported to have said: “ I am God almighty dwelling in man.” A core belief of this New Prophecy in its earliest form was that the Heavenly Jerusalem would shortly descend from heaven and be located at the little Phyrgian town of Pepuza, about twenty miles northeast of Hieropolis.

Along with its two prophetesses, Prisca and Maximilla, Montanism was distinctive in having ecstatic outbursts, speaking in tongues and prophetic utterances. They believed their prophetic ‘oracles’ were revelations of the Holy Spirit and should be regarded as supplementing ‘the ancient scriptures.’ Members of the Montanist sect gathered together and wrote down their pronouncements.

They thought their mission was in the final phase of revelation. Maximilla said: “After me … there will be no more prophecy, but the End.” Montanus’ followers developed ascetic practices and disciplines in the face of what they saw as the growing worldliness of the Church and the impending approach of the end of the world. Their movement spread quickly and was soon found in Rome and North Africa.

At first, the Church didn’t quite know what to do with the Montanists. Eventually the bishops and synods of Asia Minor began to declare the new prophecy of Montanism was the work of demons and they were cut off from the fellowship of the Church. The bishops of Rome, Carthage and the remaining African bishops declared them to be a heretical sect. Hippolytus (170-235), in The Refutation of All Heresies, said the following about the Montanists:

But there are others who themselves are even more heretical in nature (than the foregoing), and are Phrygians by birth. These have been rendered victims of error from being previously captivated by (two) wretched women, called a certain Priscilla and Maximilla, whom they supposed (to be) prophetesses. And they assert that into these the Paraclete Spirit had departed; and antecedently to them, they in like manner consider Montanus as a prophet. And being in possession of an infinite number of their books, (the Phrygians) are overrun with delusion; and they do not judge whatever statements are made by them, according to (the criterion of) reason; nor do they give heed unto those who are competent to decide; but they are heedlessly swept onwards, by the reliance which they place on these (impostors). And they allege that they have learned something more through these, than from law, and prophets, and the Gospels. But they magnify these wretched women above the Apostles and every gift of Grace, so that some of them presume to assert that there is in them a something superior to Christ.

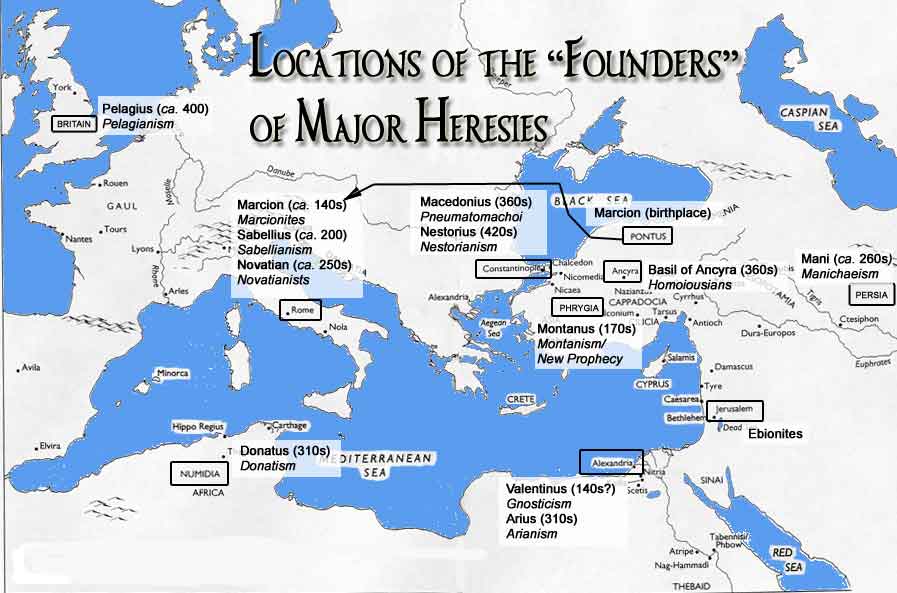

The influence of Montanism on the development of the New Testament was the opposite of that from Marcion’s teaching. Where Marcion motivated the Church to recognize the breadth of its written authoritative writings, the insistence of Montanus on the continuous gift of inspiration and prophecy led the Church to emphasize the final authority of apostolic writings as their rule of faith. See the following map for where to find the founders of early church heresies.

Despite the clever syncretism of heresies like Gnosticism, Montanism and Marcion, the rule of faith embodied in the Scriptures was not lost. In spite of Marcion, the early Church affirmed the 66 Old Testament books of the Palestinian canon as the Word of God. The claims by Gnostics and Montanists for additional revelation equal to those of the Gospels and the Epistles faded and died as the New Testament canon crystallized. By 100 AD, all 27 books of the NT were already in circulation and the majority of the writings were in existence twenty to forty years before this. All but Hebrews, 2 Peter, James, 2 John, 3 John, Jude and Revelation were universally accepted, according to NT Scholar F. F. Bruce by that time.

Information on the creeds and heresies discussed here was taken primarily from Early Christian Creeds and Early Christian Doctrines by J. N. D. Kelly; A History of Heresy by David Christie-Murray; and The Canon of the New Testament by Bruce Metzger. For more on the early creeds and heresies of the Christian church, see the link: “Early Creeds.” Part 1 of “Heresy, Canon and the Early Church” is linked here.