Whistling in the Wind Against Insys

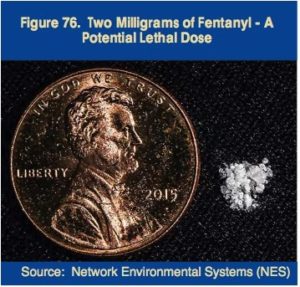

John Kapoor, the founder and former CEO of Insys was found guilty in May of 2019 of federal racketeering conspiracy charges for his role in Insys’s kickback scheme to boost sales of Subsys, its fentanyl spray, which is 100 times more powerful than morphine. His four co-defendants, former Insys executives and sales managers Michael Gurry, Richard Simon, Sunrise Lee and Joseph Rowan, were found guilty of federal racketeering conspiracy charges as well. Reuters, FiercePharma and NPR reported Kapoor was found guilty of running a nationwide scheme to pay doctors to prescribe Subsys by retaining them as speakers for what were sham events at strip clubs and expensive restaurants.

The FDA approved Subsys in 2012, but only to treat severe cancer pain. Prosecutors said Kapoor directed efforts to defraud insurers who were resistant to paying for Subsys, which could cost tens of thousands of dollars a month. Insys allegedly set up a call center where employees pretended to be from doctor’s offices. “Jurors heard phone calls in which Insys employees made up diagnoses to ensure that insurance companies covered Subsys.” Alec Burlakoff, the former director of the paid speaker program was seen in an internal promotional video (dressed as a dancing bottle of Subsys) where he and other sales managers were rapping about wooing physicians and capitalizing on opioid titration, boosting dosages of patients who develop a tolerance to the drug.

To be great, it takes a decision to be better than the competition. . . . Get a speaker you can meet with over supper. We can come to your office. We can go and bring some lunch in. While your staff is getting fed we can start discussing Subsys.

Burlakoff reached a plea deal in November and went on to testify against Kapoor. In early April he pleaded guilty and turned state’s evidence in Arizona, implicating Insys executives in a parallel lawsuit. He was forced to forfeit $9.5 million to the state.

Former Insys sales representative Holly Brown testified that Sunrise Lee gave a doctor a lap dance at a Chicago club in 2012. Brown said she saw Lee sitting on the doctor’s lap, “kind of bouncing around. . . . He had his hands sort of inappropriately all over her chest.” Lee is a former stripper turned regional sales manager for Insys. She was hired as a regional sales manager despite having no experience with pharmaceuticals. The Washington Post reported that her only previous managerial experience included running an escort service.

The doctor was Paul Madison who ran a notorious, “shady pill mill.” Madison’s “speaker” events were held at a Chicago restaurant owned by Kapoor and were attended by his friends instead of clinicians. “The idea was these weren’t really meant to be educational programs but were meant to be rewards to physicians.” Insys paid Madison over $70,800. He was convicted in November on unrelated fraud charges for billing insurance companies for chiropractic manipulations that were never performed.

Kapoor, Lee and the other co-defendants denied any wrongdoing. Lee’s attorney specifically denied the lap dance allegation in court and accused prosecutors of “objectifying her in the same way … Dr. Madison did.” The heart of Kapoor’s defense argument was he was unaware of the illegal schemes, blaming Burlakoff and other former employees who pled guilty and then testified for the prosecution.

NPR said Kapoor is among the highest-ranking pharmaceutical executives to face trial for actions taking place in the midst of the opioid epidemic. It was the first successful prosecution of top pharmaceutical executives for crimes related to illegally prescribing and marketing opioids. U.S. Attorney Andrew Lelling said: “”This is a landmark prosecution that vindicated the public’s interest in staunching the flow of opioids into our homes and streets.” The guilty verdict could influence the cases against other pharmaceutical executives, as with Purdue Pharmaceuticals. See “The Tale of the OxyContin Lie” and “Giving an Opioid Devil Its Due” for more on the Sacklers and Purdue Pharmaceuticals.

Last year Insys agreed to pay $150 million over five years to end a Justice Department investigation into the bribery and kickback scheme. Since 2015, Insys shares have fallen 90 percent in value. On June 5, 2019, Insys Therapeutics agreed to settle the government’s separate criminal and civil investigations for $225 million. As part of the criminal resolution Insys will plead guilty to five counts of mail fraud, and pay $195 million to settle allegations that it violated the False Claims Act. Insys has been named in approximately 1,000 lawsuits over Subsys.

According to the charging document, from August 2012 to June 2015, Insys began using “speaker programs” purportedly to increase brand awareness of Subsys through peer-to-peer educational lunches and dinners. However, the programs were actually used as a vehicle to pay bribes and kickbacks to targeted practitioners in exchange for increased Subsys prescriptions to patients and for increased dosage of those prescriptions.

Then on June 10th, the Wall Street Journal reported Insys filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy. This means the U.S. Justice Department will have to share available money with other unsecured creditors, suggesting it almost certainly will not collect its settlement in full. More than 90% of the company’s revenue came from opioid sales, but it wasn’t enough to cover the costs of lawsuits and investigations. How much the government collects depends on how much Insys can raise by selling its assets and the competition from other creditors. These other creditors include the U.S. Attorneys Office in Massachusetts, and the law firms who defended Insys and its former executives, including Kapoor. Insys spent more on legal costs in the first quarter than it did on research and development, sales, and marketing combined.

The company’s chapter 11 filing on Monday marks the first corporate bankruptcy directly linked to the nation’s opioid crisis, but more are possible as corporations struggle to dig out from under liabilities stemming from accusations that they profited from addiction.

Leo Beletsky, a professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University, told NPR the trial against Kapoor and Insys overlooked broader issues, such as drug companies legally spending billions of dollars to maximize the use of their medications. “We need to think much more deeply about how we regulate the pharmaceutical industry and how we prevent these kinds of practices from occurring in the first place.” Yet there are no major legislative efforts to regulate the pharmaceutical industry. Hopefully Beletsky’s suggestion will be acted on and not become another example of whistling in the wind against attempts to hold pharmaceutical companies like Insys accountable for their actions.

For more on Insys and fentanyl, see “Fentanyl: Fraud and Fatality” and “A Time of Reckoning Is Coming.”