Kratom Ping-Pong

A 25 year-old man was driving to work on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in Chester County PA on June 27, 2018 when his car veered into the right lane, struck a curb and flipped over. The West Chester County coroner ruled he died of “acute mitragynine intoxication.” With the exception of the equivalent amount of caffeine in a cup of coffee, there were no other drugs in his system. A Montgomery County Pennsylvania woman died in May of 2018 from multiple drug intoxication. She had cocaine, heroin, fentanyl and mitragynine (kratom) in her system.

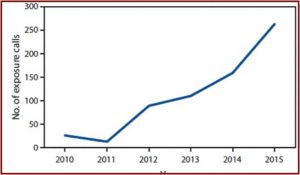

According to The Inquirer in “Deaths from kratom,” there have been at least four kratom-related overdose deaths reported in the Philadelphia area since 2016. Two of those deaths in Chester County occurred in 2018 and listed kratom as the sole cause of death. The website OverdoseFreePA, which tracks overdose fatalities, reported there have been 27 deaths in 2017 where kratom was present. NMS Labs, a nationally known forensic lab in Willow Grove PA, reported that from January to June in 2018 they found kratom in the postmortem toxicology cases of 303 deaths. Often the kratom was in combination with other opioids.

Kratom activists and the federal government have been playing “scheduling ping-pong” since August of 2016 when the DEA announced its intention to temporarily schedule kratom as a Schedule I controlled substance. Public and political outcry at this proposed action resulted in the DEA reversing itself, saying it would await the FDA’s “scientific and medical evaluation” of the proposed scheduling. Since then the FDA has released information on the adverse events when using kratom and its opioid properties. The agency took actions to address a multistate salmonella outbreak related to kratom. And there were FDA reports on kratom-related deaths. See: “Kratom Regulation Is Coming,” “Kratom: Part of the Problem or a Solution?” and “What Is the Future of Kratom?” on this website.

Then in May of 2018 the FDA announced it was warning three marketers and distributers of kratom products for illegally selling unapproved kratom products with unproven claims the products could treat opioid addiction and withdrawal. “The companies also make claims about treating pain, as well as other medical conditions like lowering blood pressure, treating cancer and reducing neuron damage caused by strokes.” The FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said the agency had determined kratom is an opioid analogue that “may actually contribute to the opioid epidemic and puts patients at risk of serious side effects.” He added the FDA was open to review data on the benefits of kratom through its new drug approval process. “In the meantime, I promised earlier this year that the FDA would step up our actions against unapproved and unsafe products that are being deceptively marketed for the treatment of opioid addiction and withdrawal symptoms.”

The FDA is concerned that kratom, which affects the same opioid brain receptors as morphine, appears to have properties that expose users to the risks of addiction, abuse and dependence. There are no FDA-approved uses for kratom, and the agency has received concerning reports about the safety of kratom.

Similar to the days of patent medicines, the companies receiving the warning letters said kratom could be used to lower blood pressure, relieve pain, boost a person’s metabolism, increase their sexual energy, improve the immune system, prevent diabetes, ease anxiety, eliminate stress, and help you get a good night’s sleep.

At the beginning of September of 2018 the FDA sent warning letters to two additional companies selling kratom because of their illegal claims that kratom treats or cures opioid addiction and withdrawal. The two companies receiving FDA warning letters, Mitra Distributing and Chillin Mix Kratom, were reported by MarketWatch to be selling kratom at cheap wholesale prices. The FDA letters indicate both companies claimed their kratom products could be used to “treat or cure” opioid addiction and withdrawal symptoms. The FDA warning letters also cited specific examples from the company websites they reviewed, including the following:

- “Kratom can render both mildly stimulating effects and mildly relaxing effects depending upon the measurement used. At smaller amounts, the effects tend to be slightly more stimulating; and at larger amounts, the effects tend to be more relaxing.”

- “Some [kratom users] have reported an increase in focus, attentiveness, and social confidence resulting from the responsible use of kratom.”

- “Due to the rise in opium costs and the discovery that kratom could relieve opium withdrawals, many users turned to kratom as a means to cure their addiction.”

- “It has been long reported that kratom has been used to treat a myriad of ailments including but not limited to: diarrhea, depression, diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, stomach parasites, diverticulitis, anxiety, alcoholism, and opiate withdrawal.”

Beginning in February of 2018 the FDA began an investigation into the link of several kratom-containing products contaminated with salmonella. “Interviews conducted by state and local health departments in coordination with the CDC found that a high proportion of the ill people reported recent consumption of kratom, either as capsules, powders or herbal remedies.” One of the three companies receiving warning letters from the FDA was also implicated in an FDA investigation of kratom products tainted with salmonella. This led to multiple recalls, with most marketers being cooperative. In one case, a marketer failed to conduct a voluntary recall and the FDA was forced to issue a first-ever mandatory recall order. On July 2, 2018 the agency announced the results of their investigation, saying it appears the salmonella problem has probably been occurring for some time, and was even still happening.

As of the end of May 2018, a total of 199 cases of salmonellosis in 41 states have been linked to kratom consumption; 38 percent of those illnesses led to hospitalizations. Fortunately, there have been no known deaths related to these illnesses. In addition to Salmonella I 4, [5],12:b:-, illnesses have been linked to Salmonella Heidelberg, Salmonella Javiana, Salmonella Okatie, Salmonella Thompson and Salmonella Weltevreden. A total of 81 samples of kratom were collected and tested as a direct result of the outbreak investigation, and 42 (52 percent) were found to be contaminated with salmonella. This means that users of these products had essentially a one in two chance of being exposed to this pathogen.

While kratom hasn’t been scheduled as a controlled substance yet, the DEA does list it as a “Drug of Concern.” At low doses, it produces stimulant effects like increased alertness, physical energy and talkativeness. At higher doses, it has sedative effects and can lead to addiction. “Several cases of psychosis resulting from use of kratom have been reported, where individuals addicted to kratom exhibited psychotic symptoms, including hallucinations, delusion, and confusion.”

Kratom’s effects on the body include nausea, itching, sweating, dry mouth, constipation, increased urination, tachycardia, vomiting, drowsiness, and loss of appetite. Users of kratom have also experienced anorexia, weight loss, insomnia, hepatotoxicity, seizure, and hallucinations.

At the end of July 2018 the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) released an official position on kratom that was quoted as saying: “Kratom by itself is not associated with fatal overdose.” The American Kratom Association said this clarified that it was “only when the natural ingredient is contaminated or “laced with other compounds” has it been associated with death.” The AKA then repeated its previous claim that the original data used by the FDA to warn the public about using kratom was tainted by “adulterated or contaminated kratom.” The president of the AKA said:

NIDA’s statement was consistent with these findings, and we call upon the two agencies to work together to remove the FDA’s scheduling recommendation for natural kratom and focus on protecting the rights of Americans who rely on it by removing adulterated and dangerous counterfeit products from the market.

But the AKA celebration was short-lived. According to The Washington Times, when NIDA was alerted to the AKA statement, it quickly edited the information cited by the AKA. For the FAQ, “Can a person overdose on kratom?” the website now reads: “There have been multiple reported deaths in people who had ingested kratom, but most have involved other substances.” An email inquiry to NIDA from The Washington Times said the AKA’s statement was inaccurate. “Currently, no Government agency views Kratom as a safe drug. Just because a drug is not routinely fatal does not mean it is safe.” In response to the revisions to the NIDA website, the AKA sent a letter to the NIDA director, claiming it bowed to political pressure from the FDA.

We are concerned that NIDA may be under pressure from purely political requests or demands being made by the FDA related to kratom that are not supported by the science, including research done by NIDA and its research contractors.

The science supporting adverse effects from kratom use and its scheduling as a controlled substance is not as weak or corrupted as the AKA claims. See discussions in the above linked articles on this website. It seems we might soon see the “kill shot” in the ping-pong match on kratom if the FDA recommends for the DEA to schedule it.