Psychedelic Renaissance?

Spravato (esketamine), a chemical cousin of ketamine (Special K), was recently approved by the FDA as a fast-acting antidepressant. MDMA is now in a Phase 3 clinical trial for PTSD. Psilocybin has received a breakthrough therapy designation for treatment-resistant depression by the FDA. Clinical research into the therapeutic effects of psychedelics has resumed for a variety of conditions, including depression, substance abuse and individuals living with serious medical conditions like cancer. This has led to calls for increasing the availability of psychedelics by loosening the regulatory restrictions that currently limit the drugs’ use for research.

In his book, How to Change Your Mind, Michael Pollan said beginning in the 1990s, a small group of scientists, psychotherapists and so-called “psychonauts,” have sought to resurrect what they saw as a wrongful termination of research into the therapeutic value of psychedelics. “A new generation of scientists, many of them inspired by their own personal experience of the compounds, are testing their potential to heal mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, trauma and addiction.” Others are using psychedelics in conjunction with brain-imaging technology to explore the links between brain and mind. “The hoary 1960s platitude that psychedelics offered a key to understanding—and ‘expanding’—consciousness no longer looks quite so preposterous.”

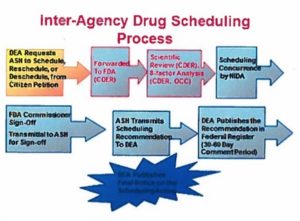

Psychedelics are currently classified as Schedule I controlled substances, meaning they have a high abuse potential; no accepted medical use; and have safety concerns, even under medical supervision. Some advocates are calling the DEA to place them into Schedule III, along with ketamine, anabolic steroids and buprenorphine. Writing for Scientific American, Rick Strassman described his own research with DMT in the 1990s. One of the most difficult impediments he faced was DMT being Schedule I.

After nearly two years of close work with FDA and DEA, an effective system developed allowing our studies to proceed. My subsequent applications to use psilocybin and LSD were much more quickly and easily approved. The New Mexico project’s success established the current American regulatory framework that has allowed for the current burgeoning of human studies with psychedelics.

Psychedelics have unique characteristics that make it difficult to fit them into the criteria used to define schedule placement. “Their safety and efficacy exist only within highly structured specialized treatment settings.” Outside of that structure, psychedelics retain their ability for abuse and are capable of debilitating, psychological damage. “How one understands the psychedelic drug state determines the assessment of risks and benefits, and thus drives recommendations for rescheduling.” William Richards, the clinical director for the John Hopkins University psychedelics research program, publicly advocates for the increased availability of the drugs, referring to their ‘inherent spirituality’ in lectures and talks.

Glorifying psychedelics’ benefits and rendering innocuous their adverse effects therefore may explain the Hopkins group’s recent publication of a paper suggesting rescheduling psychedelics into Schedule IV—the most liberal recommendation yet to appear.

Strassman suggested a new category—IA—that would acknowledge psychedelics’ abuse potential, while allowing for their use. “The security requirements established by the DEA for possession of psychedelics for clinical research—background checks of those handling the drugs, secure storage, regular inventory, etc.—would be the same as for Schedule I substances.” Significantly, only those with specialized training would be permitted to administer psychedelics to humans. With such a regulatory structure in place, He thought the clinical promise of psychedelic drugs could be realized without exposing patients to unnecessary risk. “It would also ensure that we maintain scientific rigor, intellectual honesty and high ethical standards as we continue investigating how these drugs produce their fascinating effects.”

One study published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology did produce some interesting effects with psilocybin. Two randomized controlled trials with late-stage cancer patients suggested that a single, high dose of psilocybin had “clinically significant and long-lasting effects on mood and anxiety.” There were no serious adverse events; no participants abused psilocybin; no cases of prolonged psychosis or hallucination. “No participants required hospitalization.”

Single moderate-dose psilocybin, in conjunction with psychotherapy, produced rapid, robust, and sustained clinical benefits in terms of reduction of anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer. This pharmacological finding is novel in psychiatry in terms of a single dose of a medication leading to immediate anti-depressant and anxiolytic effects with enduring (e.g. weeks to months) clinical benefits. Even though it is not possible to attribute causality of the experimental drug (in terms of sustained clinical benefit) after the crossover, the post-crossover data analyses of the two dosing sequences suggest that the clinical benefits, in terms of reduction of cancer-related anxiety and depression, of single-dose psilocybin (in conjunction with psychotherapy) may be sustained for longer than 7 weeks post-dosing, and that they may endure for as long as 8 months post-psilocybin dosing. The acute and sustained anti-depressant effects of psilocybin in this trial are consistent with a recently published open-label study of oral psilocybin treatment in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in which psilocybin (25 mg) was associated with 1 week and 3 months post-psilocybin anti-depressant effects.

Reflecting on the results of the study, Stephen Ross, MD, the director of Substance Abuse Services at the Langone Medical Center, said it possibly provides a new model in psychiatry. “This is potentially earth shattering and a big paradigm shift within psychiatry.” David Nutt, MD, PhD, of the Imperial College London said the studies were the “most rigorous controlled studies to date” using psilocybin. Others urged caution applying and interpreting the results. Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, from Columbia University said:

[W]e cannot tell if the anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of the drugs are direct results of their serotonergic effects or secondary to the mystical altered state of consciousness that they produce. Since other serotonergic agonists (eg, lisuride) do not produce this psychedelic experience it has been suggested that psychedelic drugs must bind to the 5-HT2A receptors in a special way or exhibit functional selectivity or receptor bias.”

A study of the abuse potential for psilocybin confirmed low abuse and no physical dependence potential. The study used all 8 factors required to guide the FDA and DEA recommendations for the Controlled Substance Act (CSA). They suggested placement as a Schedule IV Controlled substance. There was “no clear evidence of physical dependence and withdrawal in preclinical or clinical studies, or among those who chronically used illicit products.” The authors said the lack of therapeutic and mechanistic studies of psilocybin and other psychedelics stems from the lack of federal funding for the research and the barriers imposed by a Schedule I classification, not a lack of interest among researchers.

While some psychedelics like psilocybin may be viable therapeutic options, there simply isn’t enough modern controlled trials. James Rucker, MD, MRCPsych, PhD, of the King’s College London Institute of Psychiatry, said: “Psychedelics deserve to be investigated in modern, controlled trials if we are to know whether they are useful treatments in psychiatry, or not . . . At the moment there isn’t enough high-quality evidence to make that judgment.”

The biggest barrier to their wider use likely stems from the lack of research. Buy there are additional obstacles in doing the research. Most pharmaceutical companies aren’t interested because of the legal obstacles with Schedule I substances and because it’s not profitable to develop treatments with these drugs. The FDA approval of esketamine as a new molecular entity (NME) is the exception. Another problem is the impossibility of using a placebo control or blinding because of the identifiable effects from psychedelics. Finally, there is the challenge of obtaining sources of psilocybin that meet the standards required for the clinical trials. Rucker said:

I think everyone in this field is interested in one thing — that psychedelics get a fair hearing by Western medicine by undergoing well-funded, well-designed controlled trials . . . Then we will know whether they have any benefit, and we can judge whether this benefit is suitably balanced against any harm they might do. Until then we won’t know, and that is a worse state of affairs than knowing.

Benjamin Bell, from John Hopkins University, wrote “The psychedelic renaissance is here.” He is a proponent of psychedelic medicine, and gave a clearly biased history of how research into psychedelics was “turned off,” after Timothy Leary made the phrase “turn on, tune in, drop out” famous. “Researchers in the field are posed at the precipice of progressing forward with revolutionary studies and may conscientiously move our culture forward with them. But moving the culture will require awareness and action from scientists and citizens.” Researchers believing that psychedelics are important and useful need to recognize how that faith is a double-edged sword “and we must remain truly willing to reconsider beliefs in light of new evidence, or it will be impossible to convince the broader public to do the same.”

Researchers have the opportunity and responsibility to properly communicate their findings and recommendations to the public. He thought this was vital if psychedelics were to be integrated into medical use within the wider culture. Meaningfully, he then said: “It is important to remember psychedelics are not the ultimate panacea for treating mental health concerns.” With time and reams of further research, they may become invaluable components of the medical and mental health toolkit. If the research is carefully and systematically done, I’d cautiously agree.

Let’s not repeat the mistake made with marijuana—failing to reschedule it so research into its risks and benefits is easier to do. The science—not the rhetoric—should be the deciding factor in the medicalization and the legalization of psychedelic substances. Rescheduling psychedelics as suggested by Rick Strassman seems reasonable and would permit the researchers holding back from doing psychedelic research to forge ahead. Some psychedelics, like psilocybin, appear to have potential while ketamine and the ketamine knockoff Spravato increasingly ring alarm bells for me because of their abuse potential and the quickness with which their effects seem to fade. For more information on ketamine and esketamine, see: “Hype and Concern with Esketamine” and “Is Ketamine Really Safe & Non-Toxic?”