Categorizing Americans by Their Religious Beliefs and Practices

Religious surveys continue to report their results within pre-defined, conventional religious categories such as Evangelical Protestants, Mainline Protestants, Catholics, Mormons, Orthodox Christians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, and other faiths or affiliations. Then there are those who see themselves as atheist, agnostic or unaffiliated with a particular religious group—the infamous “nones.” There are literally hundreds of identities or affiliations within which Americans sort themselves. But a Pew Research Center analysis used a different kind of typology of religion in America—one that cut across denominations, uniting people of different faiths and dividing people with the same affiliation.

The new Pew typology is not meant to replace conventional affiliations. Rather, it aims to offer a complementary way to look into religion and public life in the U.S. Instead of dividing the data by separating the respondents into commonly understood groups like Catholics, Jews and Muslims, researchers used a statistical technique called cluster analysis to tease out “cohesive groups of people with similar religious and spiritual characteristics, regardless of their religious affiliation.”

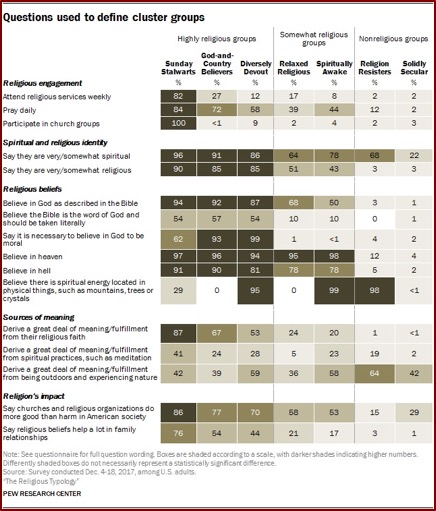

Specifically, 16 questions from the survey covering a variety of religious and spiritual domains were combined in a statistical model to define the seven typology groups. The model did not include any demographic questions or Pew Research Center’s standard question about religious affiliation, meaning that the religious tradition – or lack thereof – with which respondents identify did not affect their placement in a typology group. Though only 16 questions were used to create the groups, many additional questions were asked of the survey respondents and are included in this report.

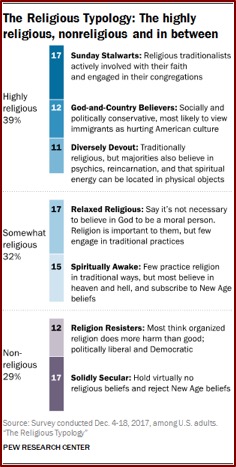

The typology sorted Americans into seven groups based on the religious and spiritual beliefs they shared, how actively they practice their faith, the value they place on their religion, and some other sources of meaning and fulfillment in their lives. “Race, ethnicity, age education and political opinions were not among the characteristics used to create the groups.” See the following chart for the religious typology.

The names of the typology groups attempt to convey distinguishing characteristics in just a few words, but do so imperfectly. “For example, ‘Sunday Stalwarts’ includes some highly religious people (such as Jews, Muslims, and Seventh-day Adventists) who do not observe the Sabbath on Sunday.” Yet nine-in-ten respondents identify with Christian churches that hold services on Sunday. The broader group categories—highly religious, somewhat religious and nonreligious—are meant to communicate general characteristics about their subgroups. See the “Complete Report PDF” link for more information on these groups.

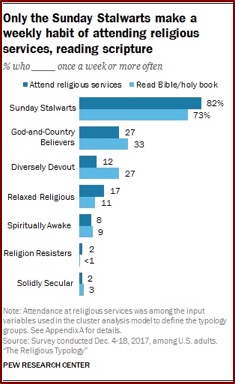

Sunday Stalwarts frequently attend religious services and read scripture. Around 80% of Sunday Stalwarts attend religious services at least once a week—three times greater than God-and-Country believers. This is roughly seven times larger than the Diversely Devout. Virtually all the Sunday Stalwarts said they were active in church groups or other religious organizations. And 72% read their Bible or sacred text daily. Religion is the single most important source of meaning in their life for 67% of Sunday Stalwarts. “No more than four-in-ten members of any others group value their faith so highly.” See the following chart.

Interestingly, God-and–Country Believers were more likely to approve Donald Trump’s performance as president. “And fully two-thirds say immigrants are a threat to American values and customs, the largest share of any group.”

Interestingly, God-and–Country Believers were more likely to approve Donald Trump’s performance as president. “And fully two-thirds say immigrants are a threat to American values and customs, the largest share of any group.”

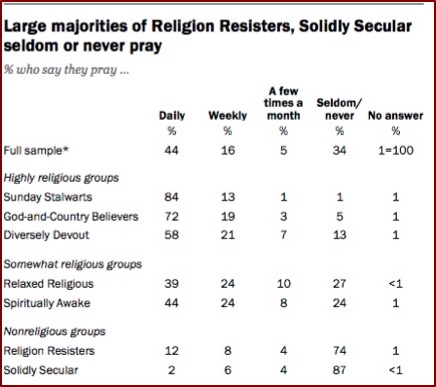

On many measures of religious practice and belief, God-and-Country Believers fall squarely between the two other highly religious groups. About four-in-ten say religion is the single most important source of meaning in their lives, well below Sunday Stalwarts but above the Diversely Devout. And 72% say they pray daily; by contrast, 84% of all Sunday Stalwarts and 58% of the Diversely Devout say they pray as often.

New Age beliefs and some demographics set the Diversely Devout apart from other highly religious Americans. The majority value religion and see themselves as religious, while “they are the only highly religious group in which majorities also embrace a variety of New Age beliefs.” They are almost twice as likely to believe in psychics as either Sunday Stalwarts or God-and-Country (68% vs. 32% and 28%, respectively) and three times more likely to believe in astrology or reincarnation.

And the belief that spiritual energy can be located in physical objects like mountains, trees or crystals was included in the cluster model and is one of the defining characteristics of this group – 95% of the Diversely Devout say they believe this, compared with 29% of Sunday Stalwarts and none of the God-and-Country Believers. [See the “Pew Research Center analysis” link for more information on New Age beliefs]

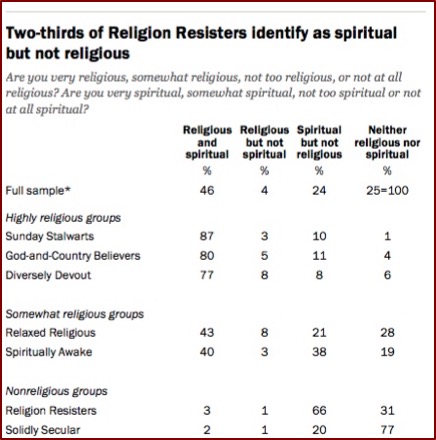

An intriguing finding was that two-thirds of Religion Resisters saw themselves as spiritual, but not religious. Almost half of all U.S. adults consider themselves to be religious and spiritual. “One-quarter of Americans (24%) say they are spiritual but not religious.” Another 77% of the Solidly Secular described themselves as neither spiritual nor religious. And very few Americans (4%) see themselves as religious but not spiritual. See the following table.

I find it extremely interesting that data on “spiritual” and “religious” fall as they do. Highly religious groups overwhelmingly see themselves as both spiritual and religious, while the Solidly Secular see themselves as not spiritual or religious in roughly the same percentages. The Religious Resisters at 66% for spiritual, not religious is consistent with what William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience described as institutional religion and personal religion. We seem to be living in a time period that sees itself much as what he described 100 years ago.

Not surprisingly, the Relaxed religious and Spiritually Awake do not put as much importance on religion as the highly religious groups. “By contrast, the vast majority of Religion Resisters (89%) and the Solidly Secular (93%) express that religion is “not too” or “not at all” important in their lives.” Most Solidly Secular and Religion Resisters say they seldom or never pray—the mirror image of Sunday Stalwarts and God-and-Country Believers. See the following table.

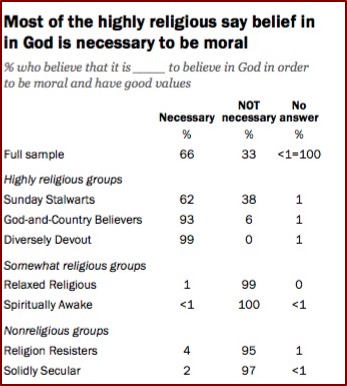

Most of the highly religious say a belief in God is necessary to be moral. The Sunday Stalwarts (62%) had a slimmer majority saying a person needed to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values. Conversely, nearly all of those who were in the somewhat religious or nonreligious groups said it was not necessary to believe in God to be moral. See the following table.

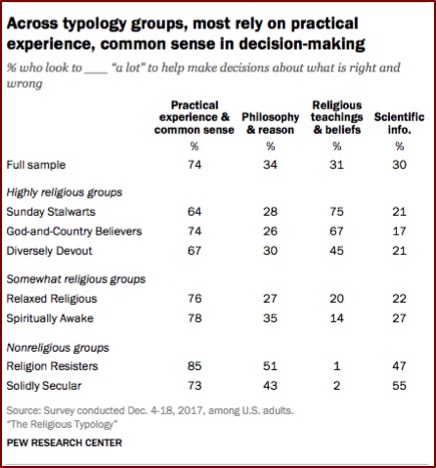

When making decisions about right or wrong, respondents were asked which of four potential sources of guidance—religious teachings and beliefs, philosophy and reason, practical experience and common sense, or scientific information—helped them make decisions about right and wrong. Majorities in all of the typology groups turned to practical experience and common sense for guidance. Many people in the highly religious groups relied on religious teaching and beliefs. Religious Resisters (47%) and Solidly Secular (55%) looked to scientific information for guidance on matters of right and wrong. See the following table.

I have merely scratched the surface with this new typology by the Pew Research Center. For example, none of the data on “Politics and Policy” was included. Nor were the demographic characteristics of the religious typology groups included. Would you be surprised to discover that one-third of all Sunday Stalwarts were over 65; and that among nonreligious groups three-in-ten adults were under thirty? The advantages of this new typology included a way to bypass the limitations of a conventional typology without losing the significance of some of the data. The religious-secular continuum remains without the restrictions inherent with conventional categories. See the Following chart for the questions used to define the cluster groups.

What stands out with this new typology by the Pew Research Center for me is that many of the findings previously attributed to the conventional categories of Christianity such as “Evangelical “are equally true for other religious groups that fit into the Sunday Stalwarts group. The questions used to define the cluster groups extended the data to religious conservatives of all faiths. For example, when asked about whether belief in the Bible should be taken literally, the question was worded as “Bible/holy book.” And when asked whether or not someone believed in the God of the Bible, one of the options was “Don’t believe in God of the Bible, do believe in higher power.” The influence of conservative beliefs and practices of religious engagement, spiritual and religious identity, religious beliefs, sources of meaning and religion’s impact is not limited to just Christian Evangelicals.