Bill W. and His LSD Experiences Part 2

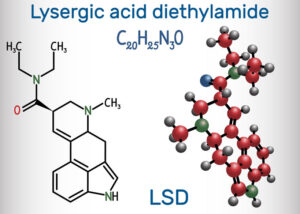

Betty Eisner was an American psychologist who pioneered the use of hallucinogens, particularly LSD, as adjuncts to psychotherapy. Along with Sydney Cohen, she originated the practice of using both male and female therapists during psychotherapeutic hallucinogenic sessions. She also served on the board of advisors for the Alfred Hofmann Foundation. Hofmann was a Swiss scientist and the first person who synthesized and then accidentally ingested LSD, thus learning of its psychedelic effects. But it also seems Eisner was present when Bill W., cofounder of A.A., first tried LSD.

In 2002, Eisner completed an unpublished manuscript that documented her recollections and correspondence about the early work with psychedelics, “Remembrances of LSD therapy past.” “Remembrances” contains several references to W. or W. Wilson (Bill W.) and Tom Powers. She said in the fall of 1956 and early 1957, there was a boiling pot of activity surrounding dozens of people who had taken LSD and/or mescaline.

And we discussed them, Sid and I – and Al, and Humphry Osmond when he visited, and people like Tom Powers who came from the east coast to experience LSD, bringing W. Wilson from AA on several trips. Every one of the people wanted to talk about their experiences, experiences which were so unique that each one of us was busy trying to make sense of all the phenomena which were occurring, and to fit them into some intelligible description, category, and understanding.

In a January 12, 1957 letter to Ewing Reilly, who was funding Cohen and Eisner’s research at the time, she mentioned that one of the hypotheses she wanted to test was that when A.A.’s were really close to accepting the Third Step, were they also “really open to what LSD can do for them.” In a February 13, 1957 letter to Tom, Betty said after dropping him off at Miramar, she had the thought that while he spoke well about not being able to help Bill (W. Wilson, co-founder of A.A.), “the words are not yet synchronized to the music.” She closed her letter asking Tom to give Bill her best regards and tell him it was a real pleasure to meet such an interesting, extraordinary, and powerful person—and challenging problem to himself and others.

On February 16, 1957, Sid, Betty Tom and Bill all participated in the very first “group session” with LSD. It had been Betty’s idea, as she wanted “to see what would happen” if everyone simultaneously took LSD, blurring the line between patient and facilitators. Not sure what the result would be, she conservatively proposed that they should all take a low dose of 25-gamma LSD. On previous occasions they had all taken larger doses of LSD. When Bill came into the room, she knew it would be his session.

Sid was waiting for us in his office at the hospital and there were warm greetings to Tom and W. At 12:20 we took the drug… W. had taken 50 gamma — the rest of us 25. When offered the little blue pills and was told by Sid to take what he wanted, he said — ‘Never say that to a drunk,’ and took two… it was 35 minutes later when he said he felt stirred by the music, and 10 minutes after that when he began talking. Throughout the session he rarely would admit feeling the drug or its action, but about the time he started talking quite a bit in a more relaxed way his face changed, he looked much younger, and the tension began to go.

Tom and Betty took turns in the role of therapist; Sid Cohen was mostly quiet. There were two important dynamics to the problem(s) uncovered that she was hesitant to say much about. The issues were Bill’s experience of himself as unloved and the perception that it was because of his parents that this occurred. Bill’s family history noted in Pass It On is consistent with these two interpretations. She thought Tom jumped “too many levels and lost W.” At other times, she thought he was “off the beam.” At around 4 pm, Bill appeared to be coming out of it and rebuilding his defenses. Later at dinner, she thought her husband Will really got through to Bill a couple of times on “the shared bridge between them of depression.”

On February 26, 1957, Tom wrote to Betty, saying her report of their February 16th session came that day. He said he thought that both her and Will were good for Bill, because they were among the few people who were interested and loving enough to deal with him forthrightly and outside of “the highly forced and artificial context of his position in A.A.” He thought their session did Bill a lot of good— “and I think you and the LSD are very largely responsible.” Bill did not write until March 22, 1957, when he said: “Please forgive this late response in thanking you for all the friendship you gave so freely on my last trip to the coast. More often than you can guess, I have continued to think of you.” He added that since returning home, he felt—and hoped he acted—exceedingly well. “I can make no doubt that the Eisner-Cohen-Powers-LSD therapy has contributed not a little to this happier state of affairs.”

There was further correspondence back-and-forth between Betty and Tom in “Remembrances of LSD therapy past,” but nothing more from Bill. Tom assured Betty in an April 13, 1957 letter that his interest in LSD continued to be very keen and he was looking forward to another planned meeting and an optimum LSD session. He said the total effect of the three sessions had profoundly changed him for the good. He added that Bill was also strongly affected for the good and others noticed how much better he was. “He himself is very happy about it and realizes clearly what it is that has done it.”

In Bill W., Francis Hartigan said Bill’s enthusiasm for LSD convinced his wife Lois and Nell Wing, his secretary, to try LSD. He even convinced Farther Dowling, his spiritual advisor, to try it. Hartigan said under the supervision of a psychiatrist from Roosevelt Hospital, Bill continued with LSD experiments in the late 1950s. The New York participants were all sober. The purpose was to determine if LSD could might produce insights that were preventing people from feeling more spiritually alive. Bill agreed with Huxley’s statement that LSD’s power was that it could open “doors of perception.” He described his first experiences with LSD as similar to what he had experienced in Towns Hospital the night his obsession with alcohol was lifted.

In a long letter Bill wrote to Sam Shoemaker in June of 1958, he discussed his LSD use. He admitted he had taken it several times over the last two years and also collected considerable information about it. He rejected the allegation that LSD was a new psychiatric toy of “awful dangers.” He named several researchers he’d met in his own investigation of LSD, including Sidney Cohen, and said they found no tendency to addiction; no physical risk whatever. “The material is about as harmless as aspirin.”

He thought that prayer, fasting, meditation, despair, and other conditions that predispose an individual to mystical experiences had their chemical components. He then theorized that these chemical conditions helped shut down normal ego drives; and to that extent, “they do open the doors to a wider perception.” Presciently, he saw it would be a huge misfortune if LSD got loose in the general public without careful preparation about what the drug is and what the meaning of its effects could be. “And do believe that I am perfectly aware of the dangers to A.A. I know that I must not compromise its future and would gladly withdraw from these new activities if ever this became apparent.”

As Pass It On noted, Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass), were experimenting with LSD at Harvard. Until that time, LSD experiments has been quiet and uneventful. Their work erupted in a scandal when two of the students in their studies, both minors, has distressing flashback experiences. Leary left Harvard and went on the be famous for the slogan, “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” He tried to get involved with Bill’s LSD work in the late 1950s, but Bill did not want to include him. Bill kept putting him off until eventually, Leary stopped asking.

In “Remembrances of LSD therapy past,” Eisner mentioned Leary in a December 1962 letter to Humphry Osmond, saying it had been fun to see Leary and Alpert. The two of them had been out to California for a weekend of lectures and workshops. She noted there seemed to be quite a movement gathering around Leary and Alpert for personal research in expanding consciousness. She said she was bothered by a separateness, or special sort of language that seemed to be developing with Leary and Alpert. She then mused, “I wonder why so much of the drug work has led to fractionation rather than fusion.”

In a May 26, 1963 letter from Osmond to Eisner, Humphry said he was worried about Tim Leary, and found it hard to maintain contact with him. He said Leary had failed to get an adequate advisor on psychopharmacology and acted as if the powerful chemicals he was experimenting with were harmless toys: “They aren’t.” Osmond said in illnesses like alcoholism they may be harmless relative to the likely outcome, but that was something different.

In March of 1966 Time magazine reported that the US was suffering from an LSD epidemic. By June both California and Nevada had legislated against LSD, and by October, LSD was illegal in the whole country. All this was too much for Sandoz, which had been taking an increasing amount of flack because of LSD and psilocybin, and in April of 1966, Sandoz terminated all research contracts involved with the two drugs and indicated their willingness to turn over all their supplies to the FDA. For 26 years there was no more legal psychedelic research in the United States.

IF you are interested in reading more about Bill W. and LSD, try “Bill W. and His LSD Experiences Part 1,” or “As Harmless as Aspirin?” For more information on the therapeutic use of hallucinogens, see “Back to the Future with Psychedelics;” “The Unique Scientific Value of Ibogaine” Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3; “Ayahuasca Anonymous,” Part 1 and Part 2; “Psychedelic Renaissance?;” “Give MDMA a Chance?” and more.