An Epidemic Emerging from the Pandemic?

According to a report by Express Scripts, America’s State of Mind, the number of prescriptions filled per week for antidepressant, anti-anxiety and anti-insomnia medications increased 21% between February 16th and March 15th. COVID-19 was declared a pandemic on March 12th. Prescriptions for anti-anxiety medications rose 34.1% during that four-week period, with an increase of almost 18% during the week ending March 15. “The number of prescriptions filled for antidepressants and sleep disorders increased 18.6% and 14.8%, respectively, from February 16 to March 15.”

More than three quarters (78%) of all antidepressant, antianxiety and anti-insomnia prescriptions filled during the week ending March 15th (the peak week) were for new prescriptions.

Express Scripts is the largest pharmacy benefit management (PBM) company in the U.S., with $100.75 billion in revenues. The Express Scripts Drug Trend Report has been published annually since 1993 and provides a detailed analysis of prescription drug costs and utilization. Express Scripts said it was understandable that Americans have become more anxious as they’ve seen the COVID-19 global pandemic swiftly and dramatically upend their lives. “This analysis, showing that many Americans are turning to medications for relief, demonstrates the serious impact COVID-19 may be having on our nation’s mental health.”

The increase of anti-anxiety medications was particularly striking, given that Express Scripts’ research showed the use of these drugs had been declining over the past five years. Mental health medication trends from 2015 through 2019 recorded a decline of more than 12% in the use of anti-anxiety medications. This was among 21 million people with employer-funded insurance. There was a similar decline in the use of anti-insomnia medications, which were down 11.3%.

While the recent increased use of medications to treat anxiety, depression and sleep disorders is sudden, it is encouraging to see our members recognizing the need for help and seeking support from their physician. What’s crucial now is ensuring Americans who are experiencing symptoms of these mental health conditions have support and access to their physicians, therapists and educational resources, including digital tools and virtual care and counseling to help them cope during this time.

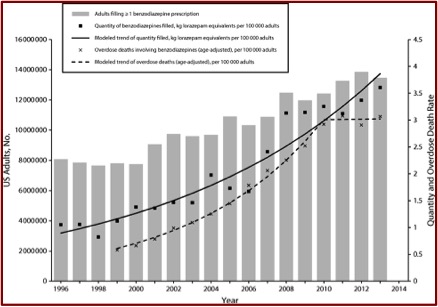

The rapid increase in anti-anxiety prescriptions is troubling, perhaps more troubling than the Express Scripts data indicates. Prolonged use of benzodiazepines is associated with tolerance and withdrawal symptoms, as well as misuse and substance use disorder. In older adults, benzodiazepines increase the risk of falls, hip fractures, cognitive impairment and drug-related hospital admissions. Contrary to what was reported by Express Scripts, the number of U.S. adults with a prescription for a benzodiazepine increased from 4.1% in 1996 to 5.6% in 2013, according to a report by the National Center for Health Studies released on January 17, 2020.

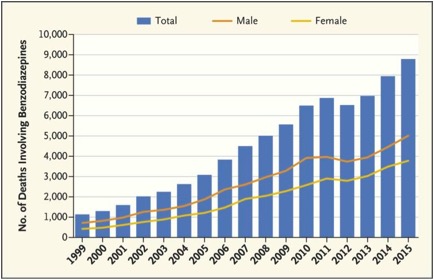

Overdose deaths that involved benzodiazepines increased from .58 per 100,000 in 1996 to 3.07 in 2010. “Data from the National Institute on Drug Abuse show that 11,537 overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines occurred in 2017.” About 85% of the 2017 overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines also involved an opioid, despite warnings that coprescribing benzos with opioids increases the risk of respiratory depression. The coprescription of benzodiazepines and opioids increased from .5% of doctor visits in 2003 to 2.0% in 2015; opioids were prescribed at 26.4% of the visits where there was also a prescription for benzodiazepines. In 2016, the FDA issued warnings on the concurrent use of opioid medications and benzodiazepines.

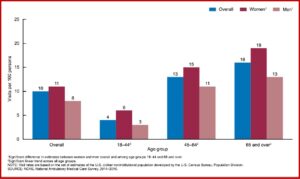

The data examined from the 2014-2016 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey included office visits where opioids were coprescribed. “Among visits at which benzodiazepines were prescribed, approximately one-third involved an overlapping opioid prescription.” More women than men were prescribed benzodiazepines and this pattern went across all age groups. This was also true when benzodiazepines were prescribed with opioids for adult patients. See the chart below.

About one-half of the visits where a benzodiazepine was prescribed were with a primary care provider (48%) and one-half (50%) were with another type of provider. Among primary care providers, general or family practice (54%) and internal medicine (39%) were the most frequent specialties. Among nonprimary care providers, psychiatrists accounted for 28% of visits where benzodiazepines were prescribed. Patients who visited the doctor frequently, six or more times in the past 12 months, were more likely (40%) to receive a prescription for benzodiazepines.

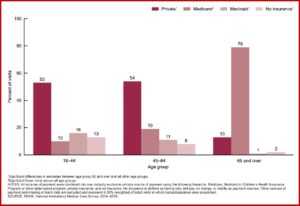

Private insurance (39%) and Medicare (38%) were the primary sources of payment for office-based visits when benzodiazepines were prescribed, followed by Medicaid (9%) and no insurance (7%). One-half the visits by adults between 18 and 44 and 45 and 64 where benzodiazepines were prescribed used private insurance, whereas 79% of visits by adults 65 and over used Medicare as the primary source of payment. 88% of the visits where in which benzodiazepines were prescribed, benzos were a continued prescription. See the chart below for the data by age group and source of payment.

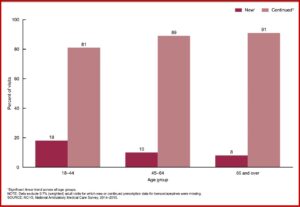

There were 23 million prescriptions of benzodiazepines, accounting for 35% of the doctors’ office visits at which benzos were prescribed. The percentage of visits having new prescriptions for a benzodiazepine and an opioid was significantly lower than the percentage of visits with continued prescriptions across all age groups. The percentage of visits with a new prescription for benzodiazepines decreased with age. But the percentage of visits with a continued prescription for benzos increased with age. See the chart below.

There were 23 million prescriptions of benzodiazepines, accounting for 35% of the doctors’ office visits at which benzos were prescribed. The percentage of visits having new prescriptions for a benzodiazepine and an opioid was significantly lower than the percentage of visits with continued prescriptions across all age groups. The percentage of visits with a new prescription for benzodiazepines decreased with age. But the percentage of visits with a continued prescription for benzos increased with age. See the chart below.

In “The Disturbing Rise in Benzodiazepine Prescriptions,” Christopher Lane reported for Psychology Today that the results of the National Center for Health Studies report were “discouraging and disappointing.” He thought we should be concerned with bringing these numbers down. “Between 2003 and 2015, the number of ambulatory visits with one or more prescriptions for a benzodiazepine increased sharply from 27.6 million to 62.6 million.” Keith Humphreys of Stanford, said “The enormous growth of benzodiazepine prescribing has flown under most policymakers’ and clinicians’ radar.” He speculated it may be because many people with a dependency on benzos are older; fewer are violent. “Or maybe people think that since they come from a doctor, they can’t be all that bad.”

In “The Disturbing Rise in Benzodiazepine Prescriptions,” Christopher Lane reported for Psychology Today that the results of the National Center for Health Studies report were “discouraging and disappointing.” He thought we should be concerned with bringing these numbers down. “Between 2003 and 2015, the number of ambulatory visits with one or more prescriptions for a benzodiazepine increased sharply from 27.6 million to 62.6 million.” Keith Humphreys of Stanford, said “The enormous growth of benzodiazepine prescribing has flown under most policymakers’ and clinicians’ radar.” He speculated it may be because many people with a dependency on benzos are older; fewer are violent. “Or maybe people think that since they come from a doctor, they can’t be all that bad.”

While primary care physicians and psychiatrists may be prescribing in good faith for anxiety, pain, and insomnia, the concern is that they are not getting the message about the risks of overprescribing and are instead inadvertently helping to fuel the crisis.

Not only are benzodiazepines a concern in office-based visit Benzodiazepines were implicated in a high rate of ED visits in the U.S., according to Medscape. About a quarter of patients brought to an emergency department (ED) were unresponsive or in cardiopulmonary arrest. More than half (55.9%) of ED visits involving benzos were for the nonmedical use (recreational use or using someone else’s medication) or for self-harm (30.4%). Among visits involving the nonmedical use of benzodiazepines, 54.8% were made by patients between the ages of 15 and 34. About 20% of ED visits for the nonmedical use of benzos involved the concurrent use of other substances. “A quarter (24.9%) of visits involved prescription opioids, a quarter (26.4%) involved alcohol, and almost half (47.8%) involved illicit drugs.”

The noted decrease in anti-anxiety medication prescriptions over the past five years by Express Scripts was likely due to its limited population sample—only those individuals with private insurance. If this assumption is correct, what is happening with benzodiazepines during the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with Medicaid and Medicare? And if benzodiazepine prescriptions tend to be renewed or continued as noted above, what does the future hold for the already problematic coprescription of benzos and other medications, especially opioids, according to the National Center for Health Studies report? It seems we may be facing an epidemic of benzodiazepine addiction emerging from the current pandemic of COVID-19. For more information on the problems with benzodiazepines, see “Doubling the Risk of Overdose,” “Are Benzos Worth It?,” “It Takes Away Your Soul” and “Dancing with the Devil.”