In Love and Tolerance

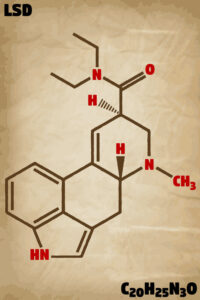

“Bill’s Story,” the first chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous, told of how Bill W. got clean and sober. He wrote: “An alcoholic in his cups is an unlovely creature.” Yet there was a realization of the importance of carrying the message to the newcomer, in love and tolerance, from the very beginning. The weakest, most unpresentable members of A.A. (Alcoholics Anonymous) or N.A. (Narcotics Anonymous) are often newcomers.

Early A.A. met frequently so that “newcomers may find the fellowship they seek.” Genuinely feeling that “the newcomer is the most important person at a meeting” is a maxim within each Fellowship. N.A. said it this way: “The newcomer is the most important person at any meeting because we can only keep what we have by giving it away.” Within a 1946 Grapevine article, “Ours Not to Judge,” Bill W. said: “We have begun to regard these ones not as menaces, but rather as our teachers. They oblige us to cultivate patience, tolerance and humility.” Chapter seven of Alcoholics Anonymous, “Working with Others,” says:

Practical experience shows that nothing will so much insure immunity from drinking as intensive work with other alcoholics. It works when other activities fail . . . Frequent contact with newcomers and with each other is the bright spot of our lives.

The need for tolerance appears regularly throughout the A.A. Big Book. In the “We Agnostics” chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous, the hypocrisy of pointing to religious intolerance when the alcoholic was intolerant towards religion itself was pointed out. The importance of tolerance for healing family relationships was noted. The essential requirement of tolerance in relating to others—within and outside A.A.—was underscored repeatedly. Succinctly in the “Into Action” chapter, Bill W. said: “Love and tolerance of others is our code.”

We find the same awareness in the N.A. Blue Book. In their “How It Works” chapter, N.A. noted that one thing will defeat them more than anything else in recovery, “an attitude of indifference or intolerance toward spiritual principles. Three of these that are indispensable are honesty, open-mindedness and willingness. With these we are well on our way.” As recovery progresses, principles such as “hope, surrender, acceptance, honesty, open-mindedness, willingness, faith, tolerance, patience, humility, unconditional love, sharing and caring” touch every area of their lives, leading to a new image of themselves. “Honesty and open-mindedness help us to treat our associates fairly. Our decisions become tempered with tolerance.”

Parallel to this thinking, In My Utmost for His Highest on May 6th, Oswald Chambers said: “It takes God a long time to get us out of the way of thinking that unless everyone sees as we do, they must be wrong. That is never God’s view.” Love and tolerance flow from a self-conscious recognition in A.A. that not only are individuals corporately members of the larger body, but they are also dependent upon one another. They need one another for sobriety.

A.A. and N.A. have been successful in maintaining solidarity within their respective fellowships by remembering that despite their open-ended criteria for membership (the only requirement for membership is the desire to stop drinking or using drugs), they are individually members of one another. This diversity of membership with minimal formal guidelines raises the potential for conflict over everything from how to apply the Twelve Steps in ongoing recovery, to where donations for service projects within the local regions and groups of the two fellowships should be allocated. These and other disputes exist within each fellowship, sometimes with heated and vehement ‘discussions’ of the issue.

But so far, the internal disputes have not led to the demise of A.A. or N.A. To the contrary, each fellowship has reported yearly increases in the number of groups established worldwide for more than thirty years. Nor has there been a disgruntled splitting of the fellowships, which seems more commonly to have occurred within the local churches and denominations of Protestant Christianity. I’d suggest this is because A.A. and N.A. are more effective in living out Romans 14:19 than the church today seems to be: “So then let us pursue what makes for peace and mutual upbuilding,” despite their diversity.

Paul’s warning in the next verse, Romans 14:20, has been too often disregarded by the church: “Do not for the sake of food destroy the work of God.” In chapter 14 of Romans, Paul discusses the way in which the church in Rome can accommodate diverse opinions on how individuals should live out their lives as members of the kingdom of God. The two disputed issues Paul gave as examples were whether or not members of the church should be vegetarian; and whether individuals should continue to honor the holy days within the Jewish religious system. Paul’s response has an almost postmodern, live-and-let-live sense to it: Each person should be fully convinced in his own mind on the rightness of his position (Romans 14:5). But as John Murray pointed out in his commentary on Romans, Paul was not just acknowledging options here, rather he was giving a command:

The injunction to be fully assured in one’s own mind refers not simply to the right of private judgment but to the demand. This insistence is germane to the whole subject of this chapter. The plea is for acceptance of one another despite diversity of attitude regarding certain things. Compelled conformity or pressure exerted to the end of securing conformity defeats the aims to which all the exhortations and reproofs are directed.

What keeps this from becoming a self-styled sense of merely doing what was right in your own eyes (Judges 21:25) is Paul’s clear reminder that the church in Rome does not live for its own purposes, but for the Lord’s (Romans 14:7-12). In other words, he reminds them of their surrender to and calling in Christ; they are not their own (1 Corinthians 6:19b). Everything we do in life is in reference to this basic fact. Our daily lives are a living sacrifice to God (Romans 12:1-2): “If we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord” (Romans 14:8). The Shorter Catechism of the Westminster Confession of Faith makes the same point, declaring that the chief end of humanity is “to glorify God, and enjoy him forever.” The Scriptural support given for such a declaration comes from both the Old and New Testaments:

My flesh and my heart may fail, but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever. For behold, those who are far from you shall perish; you put an end to everyone who is unfaithful to you. But for me it is good to be near God; I have made the Lord God my refuge, that I may tell of all your works. (Psalms 73:26-28)For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be glory forever. Amen. (Romans 11:36) So, whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God. (1 Co 10:31)

The context which permits Paul to exhort the church in Rome to “pursue what makes for peace and mutual upbuilding” in their relationships with one another is that his command is grounded in recognizing that their primary purpose is to “live to the Lord.” Again, we can turn to John Murray and his comments on Romans 14:12:

It is to God each will render account, not to men. It is concerning himself he will give account, not on behalf of another. So, the thought is focused upon the necessity of judging ourselves now in the light of the account which will be given ultimately to God. We are to judge ourselves rather than sit in judgment upon others.

If a “weaker” individual has scruples about whether or not they should eat meat, the “stronger” person should not look down upon him or her. Conversely the “weaker” person should not judge the “stronger” person because they do not keep to the same restrictions. Keeping or not keeping certain holy days was similarly a matter of personal preference; and the keepers and non-keepers were not to judge or despise the others for their position. “Each one should be fully convinced in his own mind.”

The proper attitude towards those with different ideas on how to glorify and enjoy God should be to avoid placing any stumbling block or hindrance in the other person’s way. Emphasizing the relationship between the two sides—abstainers and non-abstainers, keepers and non-keepers—Paul refers to them as brothers; members of the same fellowship body. If you think of your position as “stronger” because you don’t have the same scruples to avoid eating meat, “Do not for the sake of food, destroy the work of God.” (Romans 14:20a) The kingdom of God is a matter of righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit (Romans 14:17). Again, this freedom presupposes that the primary purpose for a believer is to live to the Lord; to worship and enjoy him forever.

Self-conscious recognition of the unity of individual believers should lead to their harmony in corporate relationships. Here there can be no distinction between Jew or Greek, strong or weak, “for the same Lord is Lord of all, bestowing his riches on all who call on him.” (Romans 10:12) Bill W. commented on the inclusiveness of A.A. by noting how one day he talked privately in his office with an A.A. member who was a countess and that night met a man at a meeting who used to be part of Al Capone’s mob. After retelling this anecdote in the Grapevine, the anonymous editor said: “In AA, our very diversity is a measure of our unity.”

Perhaps the ultimate example of how Twelve Step recovery and the epistle to the Romans correspond in their thinking about tolerance, unity and fellowship is when they each turn to the Golden Rule, what Jesus said was the second greatest commandment, loving your neighbor (Mark 12:28-31). In the Big Book chapter, “A Vision for You,” Bill W. commented how the newcomer would make lifelong friends in A.A., bound together by their common escape from disaster and shoulder to shoulder journey of recovery. “Then you will know what it means to give of yourself that others may survive and rediscover life. You will learn the full meaning of ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself.’”

At the current time in our culture and political climate, Christians need to see how loving others—even those we strongly disagree with—is a decree of Scripture. Paul commanded the Roman church to owe no one anything except the continuing debt to love each other, for then they will have fulfilled the law. Every one of the commandments was summed up in “‘You shall love you neighbor as yourself.’ Love does no wrong to a neighbor, therefore love is the fulfilling of the law” (Romans 13:8-10). For more on the Golden Rule, see “Doers of the Word.”

If you’re interested, more articles from this series can be found under the link for “The Romans Road of Recovery.” “A Common Spiritual Path” (01) and “The Romans Road of Recovery” (02) will introduce this series of articles. If you began by reading one that came from the middle or the end of the series, try reading them before reading others. Follow the numerical listing of the articles (i.e., 01, 02, or 1st, 2nd, etc.), if you want to read them in the order they were originally intended. This article is 17th in the series. Enjoy.