On January 21, 2025 Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals announced FDA approval for Spravato (esketamine) as a stand-alone therapy for adults with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), meaning they’ve had an inadequate response to at least two oral antidepressants. Johnson & Johnson said major depression has an estimated 21 million adults in the U.S.; one-third of whom will not respond to oral antidepressants alone. The approval of Spravator as a standalone TRD was granted after an FDA Priority Review. “The safety profile of SPRAVATO® as a standalone treatment was consistent with the existing body of clinical and real-world data when used in conjunction with an oral antidepressant, and no new safety concerns were identified.” LiveScience said the new FDA approval for Spravato as a treatment for adults with TRD came after clinical trials found that 22.5% of patients who took Spravato alone for four weeks no longer had depressive symptoms, compared to 7.6% of patients who took a placebo.

Spravato was originally approved by the FDA on March 5, 2019 as a TRD in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. Because of the risk of adverse outcomes such as sedation, disassociation and potential misuse, it was only available through “a restricted distribution system, under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).” With the most recent FDA approval, the concurrent use of an oral antidepressant with Spravato is no longer required, but the REMS was retained:

Because of the risks of serious adverse outcomes resulting from sedation, dissociation, respiratory depression, abuse, and misuse, to facilitate safe and appropriate use, SPRAVATO® is only available through a restricted program called the SPRAVATO® Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) Program.

The announcement also repeats a qualification with Spravato, namely that it is not known if it is a safe and effective for preventing suicide or for reducing suicidal thoughts or actions. Now examine the announcement from Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson made about Spravato on August 3, 2020. Janssen said the FDA approved Spravato as a nasal spray “to treat depressive symptoms in adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) with acute suicidal ideation or behavior,” BUT:

The effectiveness of SPRAVATO® in preventing suicide or in reducing suicidal ideation or behavior has not been demonstrated. Use of SPRAVATO® does not preclude the need for hospitalization if clinically warranted, even if patients experience improvement after an initial dose of SPRAVATO®. SPRAVATO® carries a Boxed Warning regarding a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) and the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Erick Turner, a former reviewer of psych meds for the FDA, said: “The FDA has *not* approved esketamine for suicidal ideation. But the indication for which it was approved was worded [in a way that] will mislead many people into thinking that it was. How could the FDA allow Janssen to get away with this slick marketing?” See “Doublethink with Spravato?”

This kind of doublethink about what Spravato will treat is confusing and concerning. Doublethink was a term coined by George Orwell in his 1949 novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four. It is a process of indoctrination “in which subjects are expected to simultaneously accept two conflicting beliefs as truth.” There was unease expressed about Spravato/esketamine from the time it was initially approved by the FDA.

Weak Support for Esketamine

STATNews reported that when esketamine was first approved by the FDA in 2019, some experts weren’t convinced there was enough data showing esketamine was effective. They wanted more details on how it should be used in the long run. At the time, Turner was a member of the advisory committee that evaluated esketamine, but couldn’t attend the meeting about esketamine. He said: “The threshold has been two adequate and well-controlled trials. In this case, they only got one … Based on that, I would have voted no.” In 2019 Joanna Moncreiff and Mark Horowitz said they were surprised to see a BMJ editorial endorsing esketamine in the U.S. “on the basis of flimsy evidence.”

Evidence for the benefits of esketamine is very weak. Only one of the three trials of acute treatment presented to the FDA was positive, and the difference between esketamine and placebo was not large, especially compared to the large placebo response observed, and in view of the fact that blinding is unlikely to have been maintained. The acute trials lasted only 28 days; there is almost no data on the adverse effects of long-term treatment, yet we know from the recreational drug scene that ketamine use is associated with severe bladder problems and that prolonged use of euphoriant drugs like ecstasy can cause depression in itself.

Then in 2020 Horowitz and Moncrieff published their own review of the evidence for esketamine’s effectiveness and safety in trials submitted to the FDA, “Are we repeating mistakes of the past? A review of the evidence for esketamine.” In their review of evidence submitted to the FDA by Janssen, they said there were five studies submitted to the FDA: three 4-week efficacy trials, one discontinuation trial, and one safety trial lasting 60 weeks.

The FDA normally requires two positive efficacy trials in order to license a drug, ‘each convincing on its own’. This requirement has been criticised because short-term trials do not accurately reflect the long periods many drugs are eventually used for in practice and they discount negative trials. However, esketamine did not meet even this standard. Out of the three short-term trials conducted by Janssen only one showed a statistically significant difference between esketamine and placebo. These were even shorter than the 6–8 week trials the FDA usually requires for drug licensing.

The only positive efficacy trial found a 4-point difference of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) between placebo and esketamine. A reduction of 7-9 points on MADRS has been found to correspond to a clinically noticeable change, and a reduction of 16-17 points indicates a much-improved change. The 4-point difference corresponds then to less than a clinically noticeable change.

Furthermore, participants would have been unmasked (‘unblinded’) by the noticeable psychoactive effects of esketamine (dissociation was reported by the majority of participants); expectation effects might therefore inflate the apparent difference between placebo and esketamine.

Horowitz and Moncrieff concluded that themes from the history of ketamine were repeating. A known misused drug, associated with significant harm is promoted “despite scant evidence of efficacy and without adequate long-term safety studies were being repeated.”

Differences between Esketamine, Ketamine and Antidepressants

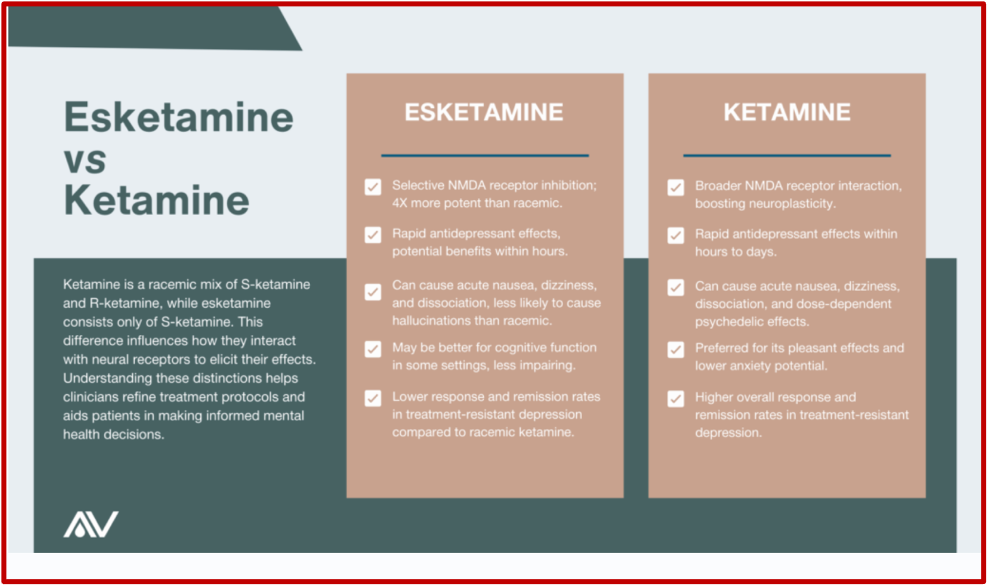

According to Avesta, the main difference between esketamine and ketamine is that ketamine is a racemic mixture with equal parts of two mirror-image molecules: S-ketamine and R-ketamine. Esketamine is only the S-ketamine form. But esketamine is more potent because it binds four times more effectively at NMDA receptors than ketamine. Early research suggested esketamine was more effective and better tolerated for treating depression because of its affinity for NDMA receptors, its rapid effects, and reduced hallucinogenic profile. “However, the latest comparative analyses indicate standard ketamine may be superior.” See the following comparison from Avesta.

Understand what Avesta is saying. FDA-approved esketamine may be less effective than ketamine. Nevertheless, Spravato has persisted as an adjunct medication for TRD, and is now approved as a stand-alone therapy, with a REMS. Just in time to compete with recent research published on the effectiveness of esketamine combined with either a selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI).

In the April 2, 2025 publication of JAMA Psychiatry, Del Casale et al published the results of their study comparing the combination of esketamine with SSRIs or SNRIs for treatment-resistant depression. Del Casale et al said in “Estketamine Combined with SSRI or SNRI for Treatment-Resistant Depression” they wanted to see if there were real-world differences when esketamine+SSRI was compared with esketamine+SNRI. This retrospective study used data with a 5-year time window from the first esketamine trial. And it used medical records from more than 90 health care centers across 20 countries. The primary outcomes which were included were: all-cause mortality, hospitalization, depression relapse and suicide attempts.

Medscape said research prior to Spravato’s approval as a monotherapy treatment for TRD suggested either antidepressant combined with esketamine was effective for TRD. “The retrospective cohort study of more than 55,000 participants with TRD showed that adding an SNRI to esketamine nasal spray was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause mortality, hospitalization, and depression relapse than using add-on SSRI.” But Esketamine plus SSRI was linked to a lower incidence of suicide attempts. Both treatment combinations were linked with reduced outcomes, but there were clear differences between them.

Results showed that in the overall study population, relapse rates for depression (17.8%), all-cause mortality (7.2%), hospitalization (0.1%), and suicide attempts (0.4%) were low throughout the 5-year observation period.

However, the group receiving esketamine plus an SNRI vs add-on SSRI had a significantly lower relapse rate (14.8% vs 21.2%; risk ratio [RR], 1.43) and lower rates of all-cause mortality (5.3% vs 9.1%; RR, 1.72) and hospitalization (0.1% vs 0.2%; RR, 3.01; all P < .001)

Although low in both groups, incidence of nonfatal suicide attempts was slightly but significantly lower in the group receiving esketamine plus an SSRI (0.3% vs 0.5%, P = .04).

There seems to have been a disregard of the evidence that esketamine failed to meet the protocols for clinical trials in the FDA. The FDA oversees clinical trials “to ensure they are designed, conducted, analyzed and reported according to federal law and good clinical practice (GCP) regulations.” The regulations help support effective medical product development, “while assuring trials generate the robust evidence needed to assess product safety and efficacy.” Has the agency demonstrated that it ensured good clinical practice by approving and then retaining Spravato as a new approach for treating major depression?