As Christians, we often think of the Psalms as songs to be sung. The word psalm means “a song sung to an instrumental accompaniment.” Yet we can see as we read through the Psalms that many were written not to be sung, but as poems, expressing the praise of the psalmist, the sense of puzzlement of the psalmist, or the joys and sorrows of the psalmist. “They are poems of the spiritual life.” Psalm 19 stands out as one of the greatest of these poems. C.S. Lewis said of Psalm 19: “I take this to be the greatest poem in the psalter. And one of the greatest lyrics in the world.”

In his commentary on Psalms 1-50 for Word Biblical Commentary series, Peter Craigie said it was hard to disagree with such a judgement, “for the psalm combines the most beautiful poetry with some of the most profound of biblical theology.” The psalmist moves from the universe and its glory to the individual in humility before God. The key clause is “there is nothing hidden from its [the sun’s] heat” in verse 19:6. This clause simultaneously marks the transition between the two parts of the psalm and links them together.

Just as the sun dominates the daytime sky, so too does Torah [meaning Law] dominate human life. And as the sun can be both welcome, in giving warmth, and terrifying in its unrelenting heat, so too the Torah can be both life-imparting, but also scorching, testing, and purifying. But neither are dispensable. There could be no life on this planet without the sun; there can be no true human life without the revealed word of God in the Torah.

According to Sinclair Ferguson, Psalm 19 is a psalm of orientation—a psalm that gives basic instruction for living a godly life; to understand it through godly eyes. It is meant to be memorized and recited, as verse 14 suggests: “Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in your sight.” If you get the building blocks of this psalm into your life, “then much of your life will be simplified and clarified.”

It has two sections, addressing the general revelation of God in creation and the special revelation of God in Scripture. Each segment begins with a general statement and then provides specific illustrations of what it declares. In both sections the psalm is a declaration of the wonder and splendor of God’s self-revelation. In verses 1 to 6, the psalmist speaks of the almighty God who reveals himself in the glory of creation. Verses 7 to 14 tell us that this same mighty God, who revealed his glory in creation, is the covenant Lord, who reveals his personal will in his word. “God reveals his majesty in the book of nature, and he reveals his will in the book of Scripture.”

“The heavens declare the glory of God and the sky above proclaims his handiwork” (Psalm 19:1). Ferguson said if you have the spectacles to see, everything within creation bears the stamp: “made by God.” This proclamation sounds throughout the day and the night. It goes throughout the earth, to the end of the world. This knowledge is universal.

The psalmist tells us, the heavens communicate this knowledge to us wordlessly. They pour forth speech, even though they use no words. Even though no sound is heard from them, their voice goes out into all the earth. Both the night and the day sky demonstrate God’s glory. This wordless speech extends throughout the entire world. All the earth is beneath God’s awesome heavens.

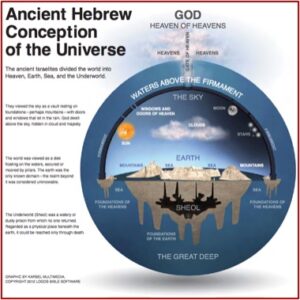

In his commentary on the Psalms, Tremper Longmen noted the word for “sky” in verse 19:1 is rāqîa, the same word translated in Genesis 1:7 as “expanse” or “firmament.” A Handbook of the Psalms said the firmament was thought of as a solid plate, as we find in Job 37:18: “Can you, like him, spread out the skies, hard as a cast metal mirror?” This plate kept the waters above from the waters below (Genesis 1:6). The Hebrews seemed to have a three-tiered cosmology of the universe, with the earth in the middle between the heaven above and the deep beneath, as in the illustration below. For more information on the ancient Hebrew conception of the cosmos, see “Why Is the Sky Blue?”

To the ancients, without the modern knowledge of the actual vastness of the heavens, the sky still gave a sense of transcendence, of someone above them. “Even today, with all of modern science’s descriptions and explanations, it is not rare for us to have our minds stunned by God’s incredible creation.” No one can escape the truth that day and night the heavens declare the glory of God. As Paul essentially said in the first chapter of Romans, “That revelation given to us is so clear, that nobody can consistently resist it.”

The sun illustrates this. It leaves its tent and “runs its course with joy,” from the morning until the evening: “There is nothing hidden from its heat.” In Scripture and Cosmology, Kyle Greenwood said Psalm 19 has an ancient Near Eastern understanding of the cosmos. Both the earth (v. 19:4) and the heavens (v. 19:6) are said to have ends, or points of termination. This suggests a flat earth, illustrated in the graphic above. In Psalm 19:6, where the sun rises and completes a circuit of the heavens, it implies an earth-centered cosmos: “It’s rising is from the end of the heavens, and its circuit to the end of them, and there is nothing hidden from its heat.”

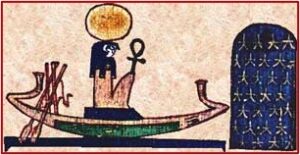

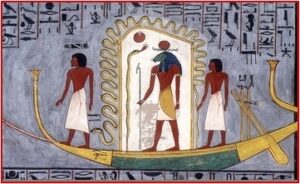

There is also an interesting parallel to the sun running its course in Psalm 19 within Egyptian mythology. Ra, the creator god and god of the sun, traveled across the sky in a barque or barge called the Mandjet providing light for the world. He then switched to the Mesektet Barque to descend to the underworld (Sheol in ancient Hebrew mythology) and made the journey back to reappear each day on the eastern horizon. “The progress of Ra upon the Mandjet was sometimes conceived as his daily growth, decline, death, and resurrection and it appears in the symbology of Egyptian mortuary texts.”

The Covenant Will of the Lord

In verse 7 there is an abrupt change of subject from God’s creation to God’s law, written in a wisdom style that Peter Craigie thought was reminiscent of Psalm 119. The bountiful nature of the Lord’s law is carefully presented in balanced poetry. One scholar sees an allusion to the tree of knowledge in Genesis 2-3 here, with further parallels between verses 1-6 and Genesis 1. While the generic word for God, El, appears only once when the psalmist reflects on the revelation of God in creation (verse 19:1), the covenant name for God, Yahweh (translated as Lord), is used when referring to God in 19:7-14. As noted by Ferguson, this implies the covenant God revealing his will in the book of Scripture.

The psalmist doesn’t just speak about the law, he praises it and says it is as more precious than gold and sweeter than the sweetest honey (Psalm 19:10). Verses 7 through 9 declare a multifaceted reality to the preciousness of the Law. The law of the Lord is perfect; the testimony of the Lord is sure; the precepts of the Lord are right; the commandment of the Lord is pure; the fear of the Lord is clean; the rules of the Lord are true. They revive the soul; make the simple wise; enlighten the eyes. They endure forever and are righteous altogether.

Once again, the concluding section of the psalm changes its tone. “The initial praise of God in nature and law evokes in the psalmist a sudden awareness of unworthiness.” After looking at the heavens and reflecting on the divine law, which naturally evokes praise, he becomes aware of his own insignificance and unworthiness in so glorious a context and feels compelled to pray. The final verse (19:14) ties together the themes of praise and prayer, with the psalmist saying:

“Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in your sight, O Lord, my rock and my redeemer.”