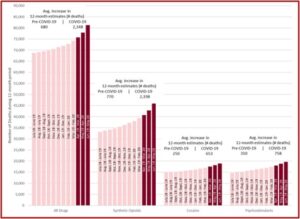

We’re now all getting ready to queue up for one of the COVID vaccines. But while our attention was on COVID surges and the political circus, there were also a surge of drug overdose deaths. The CDC reported in the twelve months ending in May 2020, there were over 81,000 drug overdose deaths in the US, the largest number of drug overdoses ever for a 12-month period. After declining 4.1% from 2017 to 2018, the number of overdose deaths increased 18.2% from June 2019 to May 2020. The increases appear to have accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The recent increase in drug overdose deaths began in 2019 and continued into 2020, before the declaration of the COVID-19 National Emergency in March. However, provisional overdose death estimates indicate that from the end of February 2020 to the end of March 2020 there was an increase of 1,511 deaths. From the end of March 2020 to the end of April 2020 there was an increase of 2,146 deaths. And from the end of April 2020 to the end of May 2020 there was an increase of 3,388 deaths. These totals were the largest monthly increases since provisional 12-month estimates began to be calculated in January 2015. See the figure below taken from the CDC Health Alert Network report.

Not surprisingly, synthetic opioids were the main driver of the increases in overdose deaths. “State and local health department reports indicate that the increase in synthetic opioid-involved overdoses is primarily linked to illicitly manufactured fentanyl.” Not all of the reporting jurisdictions (the fifty states plus the District of Columbia and New York City) had available data on synthetic opioids. Of the 38 jurisdictions with available synthetic opioid data, 37 reported increases in synthetic opioid overdose deaths for the time period (June 2019 to May 2020); 18 increases were greater than 50% and 11 increases were between 25% and 49%. See Figure 3 in the above linked CDC report for information on which jurisdictions were not included.

Historically, deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl have been concentrated in the 28 states east of the Mississippi River, where the heroin market has primarily been dominated by white powder heroin. In contrast, the largest increases in synthetic opioid deaths from the 12-months ending in June 2019 to the 12-months ending in May 2020 occurred in 10 western states (98.0% increase). This is consistent with large increases in illicitly manufactured fentanyl availability in western states and increases in fentanyl positivity in clinical toxicology drugs tests in the West after the COVID-19 pandemic. Increases in synthetic opioid overdose deaths were also substantial in other regions: 12 southern states and the District of Columbia (35.4%), 6 midwestern states (32.1%), and 8 northeastern states and New York City (21.1%) (Figure 3).

Overdose deaths from cocaine increased by 26.5% from June 2019 to May 2020. The recent deaths are due primarily to overdose deaths involving both cocaine and synthetic opioids. In contrast, overdose deaths from psychostimulants like methamphetamine have been increasing without synthetic opioid co-use. The rate of increase was faster than overdose deaths involving cocaine and is now greater than the number of cocaine-involved deaths. There was a projected increase of 34.8% of overdose deaths from psychostimulants from June of 2019 to May of 2020.

During a recent webinar, “COVID-19 and Its Impacts on Substance Abuse,” a past president of the American Medical Association (AMA) said it was imperative that we continue to talk about health issues other than COVID that are impacting our nation. “We are appropriately focused on COVID, it is still top of mind for most people, and it’s understandable that we can lose focus on other issues … but we still have to make sure we are focused on the overdose epidemic that we continue to experience in this country.” The AMA said that science, evidence and compassion must continue to guide patient care and policy change as the nation’s opioid epidemic develops into a more alarming and convoluted drug overdose epidemic.

The federal government has eased regulations that make it easier for doctors to treat patients with substance use disorder during the pandemic. But it is not clear that all states will take advantage of these relaxed policies. The DEA has issued guidance that allows practitioners to prescribe buprenorphine to new patients with opioid use disorder after a telephone evaluation. A SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services) policy allows stable methadone patients to obtain up to 28 days of take-home medication. “With social distancing recommendations and inconsistent public transportation availability, this policy assists patients that might not be able to visit an opioid treatment program on a daily basis.”

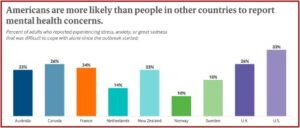

In the midst of COVID surges and the steady rise of drug overdose deaths, there is another COVID-related escalation happening with mental health symptoms in the U.S. and around the world. The 2020 Commonwealth International Health Policy Survey found that one-third of U.S. adults reported experiencing stress, anxiety and great sadness that was difficult to cope with since the COVID outbreak started. Americans were more likely than people in other countries to report mental health concern. Past research showed that Americans were already more likely to experience emotional distress, yet it seems the pandemic has contributed to higher rates of emotional distress in several countries. “The negative impact of COVID-19 on mental health has been immediate, and the pandemic is certain to have long-term effects in every country it has touched.”

Fifty-six percent of U.S. adults who reported experiencing any negative economic consequences of the pandemic also reported having mental health distress. The pandemic’s economic toll has contributed to higher levels of mental distress in other places as well. In all five countries for which reliable estimates could be calculated, people who said they experienced any type of economic insecurity since the start of the outbreak were several times more likely to also report stress, anxiety, and great sadness that was difficult to cope with alone.

The New York Times reported there is growing evidence that a small number of COVID patients with no history of mental health problems are developing severe psychotic symptoms weeks after contracting the virus. A British study published in The Lancet found 10 individuals out of 153 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 had new-onset psychosis. A Spanish study published in the journal Psychiatry Research also found ten individuals with new-onset psychotic episodes in COVID-19 patients. In COVID-related social media groups, medical professionals discussed seeing patients with similar symptoms in the Midwest, Great Plains and other places in the U.S. Neurological, cognitive and psychological symptoms could emerge even in patients who did not have serious lung, heart or circulatory problems.

A 36-year-old nursing home employee in North Carolina who became so paranoid that she believed her three children would be kidnapped and, to save them, tried to pass them through a fast-food restaurant’s drive-through window.A 30-year-old construction worker in New York City who became so delusional that he imagined his cousin was going to murder him, and, to protect himself, he tried to strangle his cousin in bed.A 55-year-old woman in Britain had hallucinations of monkeys and a lion and became convinced a family member had been replaced by an impostor.

Experts speculate that these brain-related effects may be linked to either vascular problems or surges of inflammation caused by the disease process; Another possibility is the body’s immune system response to the coronavirus. Persistent immune activation is a leading explanation for memory problems and what has become known as “COVID brain fog.” Some post-COVID psychosis patients needed weeks of hospitalization while doctors tried different medications. There have been past reports of post-infectious psychosis and mania with other viruses, including the 1918 flu, SARS and MERS.

We don’t know what the natural course of this is . . . Does this eventually go away? Do people get better? How long does that normally take? And are you then more prone to have other psychiatric issues as a result? There are just so many unanswered questions.

While we appropriately focus our attention on COVID, let’s not forget about the growing problem with drug overdoses and not neglect the emergence of post-COVID psychosis. As the AMA exhorted, science, evidence and compassion must guide us in addressing the COVID pandemic, the overdose epidemic and the concurrent rise of mental health concerns.

For other articles on drug overdoses or anxiety in the midst of COVID, see “Drug Overdose Deaths: In the Shadow of COVID-19” and “An Epidemic Emerging from the Pandemic?”